Are Quebec’s Crypto Mines Here to Stay?

At the dawn of a new energy crisis, each cryptocurrency mine eats through enough electricity to power entire cities.

PHOTO: Jay Walker

Rue Raimbault is a quaint residential street west of Sherbrooke’s downtown core, a crescent-shaped haven for seniors and families. It tucks away a stretch of waterfront properties just opposite Parc Lucien-Blanchard, where another street mirrors it.

In between the two is the Magog River, which carries small boats, paddleboards, and the people who’d come from near and far to enjoy its calm waters.

But for more than two years, the river carried the sound of an incessant whirring into the lives of residents across the way.

“Quality of life? There was none,” said Marcel Cyr, a resident on Rue Raimbault. “We were subjected to non stop noise pollution.”

Cyr first noticed the noise on a September morning in 2019, during his usual walk down to the shore from his backyard. As the only major city in the mountainous region between Montreal and the American border, Sherbrooke had long been an industrial hub. Settlers had brought lumber yards and railways to the region in the 19th century, later expanding their industrial footprint to include steel foundries and textile mills. A nearby hydroelectric dam fed the expansion, making Sherbrooke a manufacturing center.

Though the economy is now driven largely by the city’s postsecondary institutions and service sector, manufacturing remains a fixture in its industrial pockets.

Still, Cyr found the noise unsettling. He asked his neighbours if they heard it too. By the time residents concluded that the sound of rumbling engines was not a figment of their imagination, it had already gone on for 24 hours a day, every single day.

Residents soon identified the source: the noise was coming from a cryptocurrency mining facility belonging to Bitfarms, Ltd., a publicly traded company on the Toronto Stock Exchange. Bitfarms has not responded to The Rover’s multiple requests for comment.

Bitfarms was founded in 2017 by two Canadians and an Argentinian entrepreneur. Its headquarters are in Montreal’s South Shore, and its mining operations in cities around the world, though a majority are in towns across Quebec — including Farnham, Magog, Cowanswille and St. Hyacinthe.

The company struck a deal with Hydro-Sherbrooke to build their fifth mining facility in 2018; it would buy $10 million dollars worth of surplus hydroelectricity annually, invest $250 million in the facility, and potentially create 250 local jobs. It posted up in the old Sherwood Hockey building, a company that made goalie sticks, on Rue de la Pointe.

Support investigative journalism!

The building was furnished with 10,000 computer processors and outfitted to consume up to 98 megawatts of electricity, the equivalent of powering more than 39,000 homes. According to the 2021 census, there are roughly 80,000 households in Sherbrooke.

“Just one megawatt [of electricity] can power 400 homes,” said Cyr, who is a retired electrical evaluator in the private sector. “So imagine how much energy one [cryptocurrency mine] takes.”

Cyr became increasingly concerned with the facility. He noted a ten-degrees celsius increase in temperature around the building, and a visible absence of local wildlife and birds the following spring and summer. Sound level meters attached to trees across the river showed 70 decibels of noise on residential property, he says, but the company began their new relationship by denying that it caused any of it. The World Health Organization recommends under 40 decibels of noise at night to prevent adverse health effects.

For more than two years, Cyr and a committee of community stakeholders fought against the noise. In media interviews, Sherbrooke councillor Marc Denault called it a battle against Goliath.

“The noise of all those computers in the same place — and the vibrations — was huge. And we had a lot of issues regarding complaints from citizens,” Denault said. “More than 1,000 people were having discomfort with all the noise coming from the computers inside the building.”

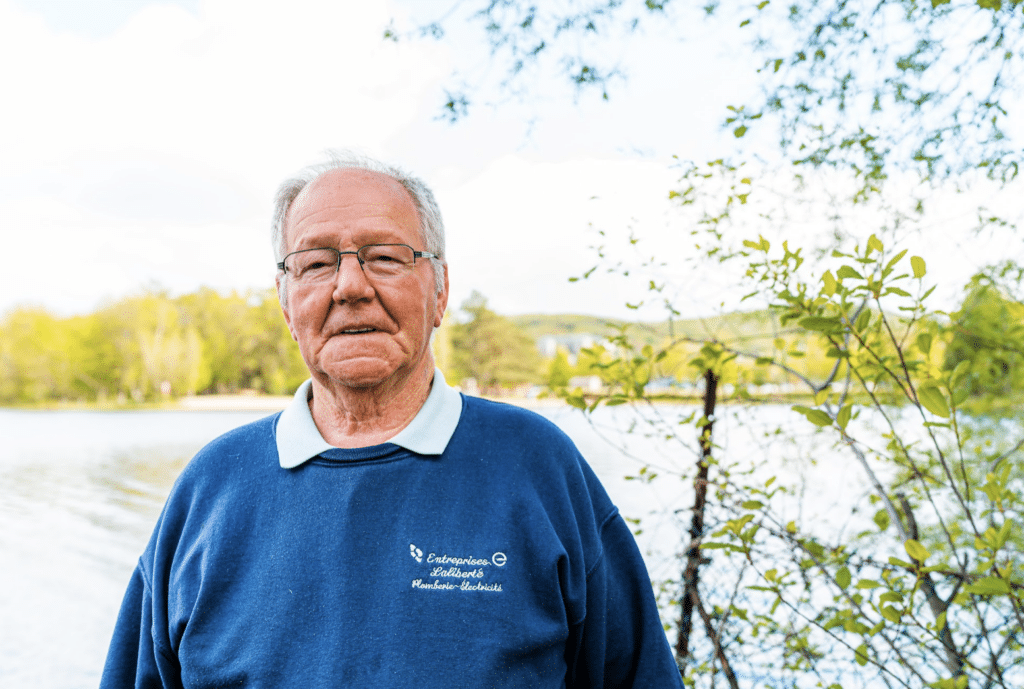

Marcel Cyr fought against the noise pollution of a crypto mine in his Sherbrooke neighbourhood. PHOTO: Jay Walker

There has been little coverage of the fight in Quebec’s Anglophone media, but Francophone outlets covered it doggedly. Radio-Canada reported a victory for residents in December 2022: Bitfarms operations at Rue de la Pointe had ceased and would move out of the building by February.

Sherbrookois had won against their Goliath; Cyr’s neighbours are busy enjoying their first summer without noise since even before the pandemic began. It was behind them now, and they’re moving on from that chapter in their lives.

But shortly after Bitfarms moved twenty minutes across town to an industrial park, it announced in April that it would open its next facility seven hours away, in Baie Comeau.

At the time this article was written, it was reported that Canadian co-founder Pierre-Luc Quimper died in West Palm Beach on Wednesday. He was 39.

***

In 2018, Hydro-Québec was met with such “sudden, massive and simultaneous” bids from crypto companies that it reported to the Régie de l’énergie de Québec it would need at least 18,000 megawatts of electricity to fulfill the supposed demand.

“The number was insane,” said a former Hydro-Québec insider who worked in regulatory processes and wishes to remain anonymous. “I think they went to the régie saying we received demands totalling almost 20,000 megawatts, which is almost doubling our peak demand. That’s huge.”

Peak demand refers to the amount of electricity reserved to power the province on the coldest day of the year, which is currently around 30,000 megawatts.

Companies like Bitfarms flocked to Quebec two years after Bitcoin had begun disrupting the financial markets in 2016. By then, it had made a name for itself as the world’s largest cryptocurrency. Bitcoin is a digital currency that can only be sent between users on the Bitcoin network. Whereas currencies across the world are overseen by central banks, there are no central banks governing Bitcoin. That’s because it was introduced as a platform with nobody in charge and no middlemen, opting instead for a purely egalitarian network of users.

But since then, the free market has given rise to a second, and arguably higher, class of users known as corporate miners. Miners help maintain the network and validate transactions between users who already own Bitcoin. As a reward for maintaining the network, miners also have a chance at earning newly minted Bitcoin. The process resembles a kind of lottery: the network is constantly putting out a complex computational puzzle, and the first miner to get the right answer wins new coins. Every ten minutes, on average, a winner strikes new Bitcoins, currently at a rate of 6.25 coins. Bitcoin was trading at $25,037.50 per coin as of publication of this article.

The network was designed so that anyone with the proper software and an internet connection has the same shot at winning new coins as the next person. But as digital currencies swelled in popularity, crypto-mining grew too. Companies were then founded on the premise of mining coins as their sole endeavor, charging users (also known as investors) fees for buying or trading coins through them. Today, corporate mines — or crypto-farms — are loaded with tens of thousands of computer processors, each racing towards solving the next puzzle and maximizing their chances of winning more coins.

“That’s why these companies have blown up,” said Dr. Jeremy Clark, an expert on cryptography and blockchain technologies, who teaches a course on Bitcoin at Concordia University. “And they keep getting bigger because if their competitors get bigger, they have to get bigger too, to maintain their share.”

The mines look like massive warehouses stacked with rows after rows of servers. But in the race towards winning as many new coins as possible, the processors must perform computational tasks non-stop. These processors consume exponentially more electricity and produce more heat than any average server. In fact, Bitcoin’s annual carbon footprint is comparable to that of Morocco, and its annual electrical energy consumption is comparable to that of Netherlands, according to the Digiconomist’s Bitcoin Energy Consumption Index.

“Ninety-nine point nine per cent of the energy being consumed for Bitcoin is for this puzzle,” Clark said. “And it’s the only way to make it work securely. No one knew a different way of doing it before.”

Quebec was attractive to Bitcoin miners for the same reasons that regions in China were: it produces local hydroelectricity (widely known as the cheapest in North America), is an area with reliable high-speed internet, and its natural climate helps save on cooling costs incurred by running processors. When the Chinese government banned Bitcoin mining in 2021, Quebec rose higher on the list of crypto-friendly destinations.

“When Bitfarms and other people started coming to Quebec, I started hearing the Quebec government talking about what they should do, what their response should be — and political stability is the fourth reason.

“You don’t want to invest a lot of money in a country and then it gets banned in three to four years and you have to leave, or your equipment gets destroyed or confiscated,” Clark said. “And so Quebec seems, as far as mining is concerned, [that] there’s no legal problem at all. I’ve never heard winds of banning Bitcoin or things like that.”

By January 2021, the insider says, Hydro-Québec withdrew their 2018 proposal to the Régie de l’énergie de Québec. The amount of business it had anticipated turned out to be more of a hope than a sure thing.

“I don’t know why the numbers of 2018 didn’t materialize,” said the former Hydro-Québec insider. “What I know for sure is that the sum of factors of all these reserves of energy for this kind of sector is no longer interesting for Hydro-Québec. They don’t want to do it.”

One of the main factors, the former insider says, began when the province took a hard look at its own electrical and environmental needs. As part of Canada’s pledge to produce net zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050, the Quebec government plans on ramping up its production of hydro electricity by 50 per cent over the next 23 years. That way, the province can power more electric cars and attract industries looking for a way to wean themselves off fossil fuels.

“Around 2021, Hydro-Québec realized that if they’re going to be an important tool for the decarbonization of Quebec, they can no longer give their energy like that,” he said. “There [will be] no surpluses available.

“And they realized if the agenda is turning into more electrification in society—especially in transportation—they can’t have these kinds of projects. I think it’s a waste and there are better uses (for our energy).”

***

Cyr walked down to the shore on a sunny afternoon in May, focused on avoiding mallard droppings that dotted his backyard. When he arrived at his dock, he pointed across the water towards the former Bitfarms factory, once the source of his stress for more than two years.

He smiled and squinted under the sun, wearing a blue sweatshirt that said “Entreprises Laliberté Plomberie-Électricité” on the chest.

“I have nothing against Bitfarms,” Cyr said. “I thank them for working with the committee and citizens in finding a solution. But the citizens also fought for a long time to return to peace.”

Along the way, Bitfarms made concerted efforts to make amends with residents. They were creative with thinking up potential solutions, like installing walls that serve as noise filters (both at the factory and on residential property) and buying residents air conditioning units to mask the sound. After more than two years of discussion between city hall and residents, Bitfarms agreed to move, paring down to three separate facilities spread across Sherbrooke.

Cyr says the final victory is credited to Denault, who came with the idea of purchasing the Rue de la Pointe facility for $5 million dollars under the Socièté de Transport de Sherbrooke (STS). The former Bitfarms building, which happens to be beside the STS, will be used to expand the city’s public transportation needs, including its goals in adding electric vehicles and offering 250 self-service bicycles around the city.

“We were blessed to have this kind of opportunity,” Denault said. “And we were blessed as a city council to have people involved who were sensible to the issue.”

Marcel Cyr. PHOTO: Jay Walker

Cyr says that before Bitfarms, there was at least one other known cryptocurrency mine that was already in operation in Sherbrooke. And as the industry continues to expand in the province, he says it’s hard to say whether welcoming more crypto-mining projects will bring more than money to towns and communities.

“They said they would bring 250 jobs, but that didn’t happen,” Cyr said. “Everything is automated inside the factories, there was almost never anybody there.

“We still don’t know what the real cost of setting up these factories are,” Cyr said. “The cost of transmission is paid for by taxpayers, and building the transmission lines alone costs a fortune. We’re paying for their development, to bring the electricity right up to the buildings.”

For a time, Cyr worried about the natural environment surrounding the former factory. But the birds have returned, he says, and the peace of mind that came with that is priceless.

“I am a lot more concerned with nature than I am with human fantasies,” Cyr said, chuckling. “Animals and the environment, they’re the most important.”

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.