Free Speech or Free-for-All? The Mega Consequences of Meta’s New Policy

Meta’s policy change eliminating fact-checking in the US represents a dangerous shift that could increase online hate, polarization, and the potential for real-world violence.

What do Blake Lively, Canada’s 2022 “Freedom Convoy” protests, the 2016 US elections, and the Qatar World Cup have in common?

Fake news.

Each of them was either targeted by or the result of disinformation that spread online via social media platforms, which is where it spreads fastest. Reputations destroyed, rioting, and an election that shook democracy to its core.

Each of them also answers the question: why should we care about Meta’s decision to essentially stop regulating its platforms in the US?

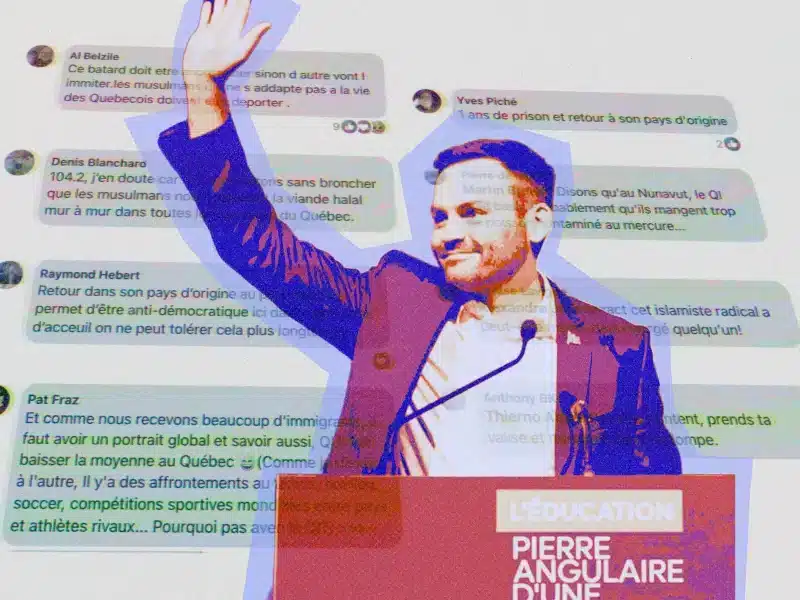

Meta, which owns Facebook and Instagram, is firing the professional third-party fact-checkers whose job it is to prevent disinformation on its platforms in the US. It will also reduce moderation on issues such as immigration and gender — the piñatas of online hate — despite the fact that posts related to immigration generated 300 per cent more hate speech on Facebook compared to other political topics, according to a Center for Countering Digital Hate’s 2021 report.

All this in the name of adapting to what Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg calls “a cultural turning point toward once again prioritizing free speech.”

And possibly, maybe, also in the name of currying favour with US president Donald Trump, the same man whose accounts Meta suspended in January 2021 following the attacks on the US Capitol, citing violations of its policies against incitement of violence. Meta is such a fan of Trump’s brand of free speech that it donated US$1 million to his presidential inaugural fund along with Google, Microsoft, Amazon, and OpenAI CEO Sam Altman.

When asked by a reporter whether he thought Meta’s turnaround was due to his past threats, Donald Trump responded, “probably.” If this really is about free speech, the decision to embrace it was not made freely.

For those who believe Meta’s policy change is motivated by a desire to promote free speech, consider that as of June 2022, half of all white supremacist groups listed by Facebook as hate groups had a presence on the platform — was that not enough freedom of speech?

Fight disinformation: support local journalism

That’s not to say that the criticisms towards Meta’s censorship are unfounded. It’s hard to defend Meta’s content moderation and fact-checking, which were clearly ineffective and uneven in their application. Meta has admitted that 10 to 20 per cent of its content removal actions may be mistakes and has been rightly criticized for blocking content regardless of context, which can suppress legitimate expression.

Extremist groups have learned to camouflage their hate speech to evade censorship, while regular users have learned to camouflage keywords about issues that are heavily censored. Human Rights Watch published a report in December 2023 documenting Meta’s “systemic censorship” and suppression of protected speech, including peaceful expression in support of Palestine and public debate about Palestinian human rights going back to 2021.

Part of the problem is that it’s impossible to appeal these decisions or to find out why they were made. My own nonprofit’s Facebook page, WeDoSomething, was banned a few years ago when all it did was promote fundraising events for communities in need.

Clearly, Meta’s efforts to manage content haven’t been working.

But the solution is not to drop fact-checking and content moderation — on the contrary.

Social media is a superspreader of fake news.

Some 68 per cent of internet users across 16 countries view social media as the primary source of disinformation contributing to increased polarization, according to a 2023 Ipsos study. Almost 40 per cent of US news consumers report unknowingly sharing fake news or misinformation on social media.

SOURCE: Elections & Social media: the battle against disinformation and trust issues

Disinformation is now the most urgent threat out of a list of 35 “plausible” global disruptions “that could reshape Canada and the world in the near future,” according to a 2024 report by government-sanctioned think-tank Policy Horizons Canada. Fifteen hundred global leaders surveyed in the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report 2024 share the same concerns about the disinformation flooding our “information ecosystem” within the next three years.

Within the next three years, algorithms designed to engage audiences emotionally rather than factually could “increase distrust and social fragmentation,” isolating people in “separate realities shaped by their personal media… Public decision making could be compromised as institutions struggle to effectively communicate key messaging on education, public health, research and government information,” the Policy Horizons Canada report says.

SOURCE: Global Risks Report 2024

Does this sound familiar?

Disinformation is the new pandemic: like a virus, it’s often undetectable, and like the COVID-19 virus, it creates fear and distrust of others — and of the institutions whose job it is to protect us, like the government.

And just as Facebook was named by 66 per cent of journalists as the leading source of COVID-19 disinformation, it is at the centre of what is being called the era of distrust. Distrust is now our default tendency: nearly six in 10 people surveyed across 28 countries say their default tendency is to distrust something until they see evidence it is trustworthy. When distrust is the default, we lack the ability to debate or collaborate.

SOURCE: 2023 Edelman Trust Barometer

And yet instead of investing in more sophisticated safeguards to stem the flow of disinformation, Meta proposes to drop these safeguards almost entirely (in the US for now) and adopt the Community Notes policy used by X, which relies on users to flag potentially misleading or false content.

How’s that working out?

Hate speech on X increased by 50 per cent between January 2022 and June 2023 (community notes was adopted in October 2022), including a 260 per cent increase in transphobic slurs, a 30 per cent increase in homophobic tweets and 42 per cent more racist tweets, according to a study by the University of Southern California’s Information Sciences Institute.

The same study indicates that tweets containing hate speech received 70 per cent more likes per day than any other kind. In terms of efficacy, Community Notes typically become visible about 15 hours after a tweet is posted, and 86 per cent of posts flagged for containing hate speech were not removed, according to the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH).

Here’s the thing: Several studies have found evidence that increases in online hate speech are associated with real-life violence. Meta is aware of this, so much so that when it announced its policy change, it also removed a sentence from its own website. The now-deleted sentence said that hate speech “creates an environment of intimidation and exclusion, and in some cases may promote offline violence.”

This is free hate, not free speech.

Here in Canada, Meta has shown the impact it can have on citizens’ trust. In August 2023, Meta blocked Canadians’ access to news on its platforms to push back at the Online News Act (Bill C-18), which aimed to force it to pay news providers for their content. Only three months later, 26 per cent of Gen Z respondents reported having less trust in the news as a result — and when citizens lose trust in the news, they also lose trust in the institutions that communicate with them through the news, like the government.

Facebook stands above all other social media platforms as a superspreader of fake news: its algorithm design is more likely to promote disinformation compared to other platforms. Facebook’s algorithms reward any content that keeps users engaged by promoting it to other users, in the hopes that it will also keep them engaged, regardless of ethics, veracity or source. And if there is one thing disinformation does well, it is keeping us engaged — whether it makes us feel outraged, comforted, or appalled, it attracts our attention by appealing to our emotions. And when we share it, we unknowingly spread it, too — which is called misinformation.

SOURCE: Misinformation and Disinformation Study, 2022, Security.org

This is why the platform has been at the centre of so many scandals, from spreading dangerous claims that Haitian immigrants eat pets — claims that led to bomb threats — and harassment, to openly promoting propaganda for the Myanmar military that contributed to the genocide of the Rohingya people.

SOURCE: TIME magazine

How did we get here?

By treating Meta like a tech business and allowing it to regulate itself — which it does not have to do in the US, thanks to Section 230 of the US Communications Decency Act which protects Meta and other interactive computer service providers from liability for content posted by third parties. The law was created almost 30 years ago to protect internet platforms from liability for many of the things third parties say or do on them — without it, the Internet as we know it would not exist.

Section 230 also allows internet platforms to “restrict access” to any content they deem objectionable. In other words, the platforms get to choose what is and what is not acceptable content, and they can decide to host it or moderate it accordingly.

This law is both the backbone and the Achilles heel of the online world as we know it. But it doesn’t have to be this way — while Section 230 provides broad immunity from civil liability, the European Union’s approach focuses more on holding platforms accountable for enforcing their own rules and removing illegal content.

Why is this not universal?

And why aren’t we addressing the algorithm that makes such laws indispensable? Our governments, so vocal about the dangers of disinformation, continue to allow Meta to keep its algorithm hidden, despite its role in shaping what we see — and what we don’t. Our ideas and beliefs are just as influenced by what we don’t get to read or see as they are by what we do.

Asking for transparency in social media algorithms is like having a say in what you eat every day. Just as our food diet affects our bodies, our information diet affects our minds, our beliefs, and ultimately, the decisions we make.

“Platforms must disclose the principles that guide their algorithms. This includes the types of data they use, the decision-making process, and the personalization goals. Transparent practices enable users to make informed choices about their digital interactions, and they hold platforms accountable for ethical algorithms.” – How Social Media Algorithms Reshape Digital Landscapes

So what can we do?

We can demand that our governments stop treating Meta as simply a tech business. With 3.065 billion active users, its every decision affects every country on the planet.

Meta is a mercenary that will work for the highest bidder to conduct what the military calls psy ops — strategic campaigns designed to manipulate beliefs, emotions, and behaviours to achieve political or military goals — whether in peace or conflict. Every military in the world incorporates psychological operations into its military strategies.

Fake news is a weapon and we are its army.

Meta’s changes will not encourage more free speech. On the contrary, fewer safeguards mean that we will be less protected from and more exposed to the influence of anyone who wants to pay for content that tells us what to think, how to vote, who to fear and what to believe.

Just this summer, US Attorney General Merrick Garland accused Russia of orchestrating a US$10 million social media campaign involving well-known conservative influencers to sway public opinion in its favour ahead of the upcoming presidential election. This is neither the first nor the last time: Russia also interfered in the 2016 US presidential elections via disinformation campaigns on social media to influence the democratic process.

Facebook, Instagram and other social media platforms have and still can connect, inform and empower us. Facebook played a crucial role in various social movements: Black Lives Matter, the Arab Spring, the #metoo movement, the protests in Iran, Occupy Wallstreet, and more.

But social media is a double-edged sword, and unlike the person who holds the sword, Meta’s algorithms have no ethics, as evidenced by Facebook’s pivotal role in the genocide of the Rohingya people. A report by Amnesty International details how Facebook’s algorithmic systems were supercharging the spread of harmful anti-Rohingya content in Myanmar, but the company still failed to act: “while the Myanmar military was committing crimes against humanity against the Rohingya, Meta was profiting from the echo chamber of hatred created by its hate-spiralling algorithms.”

Despite everything we know, there are over 3 billion Facebook users and almost 2 billion Instagram users who have almost no way of holding these platforms accountable. While we wring our hands about fact-checkers and content moderation, our beliefs, our ideas, our minds and ultimately our behaviours are affected by algorithms we can’t see. If Facebook’s algorithm were a person, it would be imprisoned many times over for fomenting violence, racism, homophobia, antisemitism, Islamophobia and misogyny, to name a few.

As Nobel laureate Maria Ressa warns, “We are ushering in a world without facts.” Removing the safeguards for users while maintaining the algorithm that makes them indispensable is like being trapped in a self-driving car with no brakes.

Let’s just hope that we don’t end up like that Tesla that drove itself off a cliff.

Did you like this column? Share it with a friend!

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.