A Community Centre Evicted, Grassroots Groups Dispersed

The 15 community organizations that operated in Centre William-Hingston in Parc-Ex were forced out when the CSSDM took back the building. While some services relocated, others closed for good.

Navneet Kaur moved to Montreal from India just two years ago without knowing English or French.

Thanks to the services of community organizations in Parc-Extension, she gave a full interview with The Rover.

“My native language is Punjabi, and I couldn’t speak or understand English. But then I started going to William-Hingston,” Kaur said. “I learned many things there… I joined the library, and used the computer and read books. It’s a great place for any person learning things.”

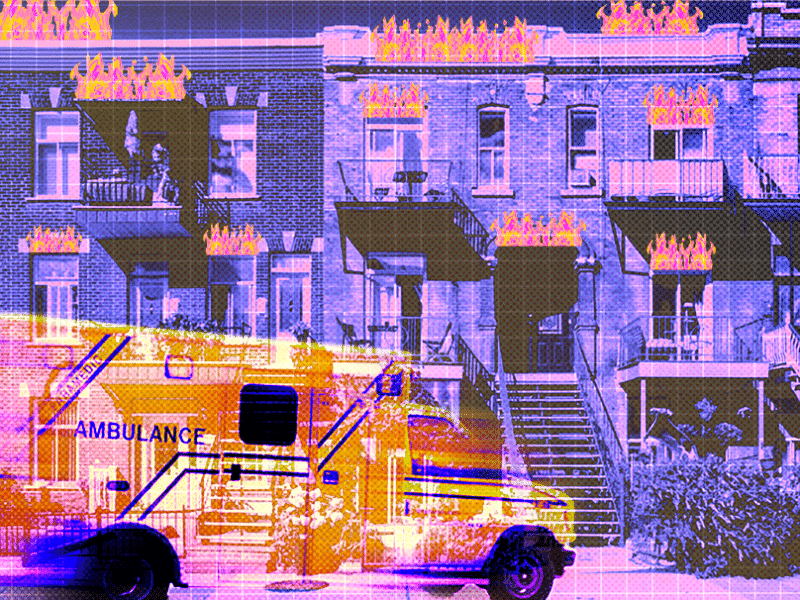

Housed in a former public high school by the Canadian Pacific train tracks in Parc-Extension, Centre William-Hingston was a one-stop shop. Fifteen community groups operated out of it, offering services that ranged from housing advocacy to after-school programs, summer camps, and settlement and language support for immigrant and refugee women.

Then, Centre de services scolaire de Montréal (CSSDM) reclaimed the building; all 15 community groups needed to be out by June 2025.

Dozens of Montreal’s community organizations have operated out of buildings owned by the CSSDM, which gained control of all school properties following Quebec’s 2020 education reform (Bill 40). These spaces, even if leased to community groups for years, could be reclaimed, renovated, or sold at any time, leaving organizations vulnerable to eviction.

Bill 40 meant elected French-language school boards were replaced by service centres like the CSSDM. These service centres are run by a board of directors that includes community members, but they are not elected by the public

Anna Kruzynski, a professor at Concordia University’s School of Community and Public Affairs and long-time community organizer, suggests that with Bill 40, Quebec is headed towards a corporatization of education.

“Anything that removes democratic control from communities makes it more difficult for community actors to then have (a relationship) with state actors… the target is now very far from them,” Kruzynski explained. “I’m always teaching that you want to find targets who can actually give you what you want, but when they’re so far away in some sort of corporate structure or even bureaucratic structure, it’s very difficult to actually win your demands.”

Support your local indie reporters!

Rose Ndjel, director of Afrique au Féminin — one of the groups that operated out of William-Hingston — remembers the letter arriving in 2021, announcing CSSDM’s plans to take back the space.

“Every year, it was postponed,” she said. Then, in 2024, the move became final.

Some of these community groups, like Afrique au Féminin, were relocated to smaller spaces.

Once occupying about 1,200 square feet in William-Hingston, Afrique au Féminin was moved by the City of Montreal to the Parc-Extension Arena. “We went to the place, and we saw that it’s only 200 feet. We lost some services that we had.”

In some cases, these groups were not provided with a suitable space for their needs. The food service program operated by the Parc-Extension Youth Organization (PEYO) required a kitchen, but the city was unable to provide one.

After 22 years, they served their final meal.

The timing of this closure could not be worse. As of July 2025, Canadians were paying over 27 per cent more for groceries than they were in July 2020, and a Statistics Canada report from spring 2024 found that nearly half of Canadians felt that the rising grocery prices were making it difficult to cover daily expenses.

The PEYO kitchen had previously served about 150 people every weekday during lunchtime, including about 50 to 70 seniors.

Afrique au Féminin provided support for all women. It was not just language classes and food aid, but an entire ecosystem of care. Services ranged from more urgent — childcare, intervention, or help with filing taxes — to more uplifting — yoga, art workshops, and intercultural cooking classes. The aim was to help women thrive, not just survive.

This was especially significant in Parc-Extension because of the large immigrant community. According to a 2016 census, 69 per cent of citizens residing in Parc-Extension were either born abroad or have at least one parent who was born outside Canada, and 48 per cent grew up learning a language other than English or French.

Other community centres caught up in the CSSDM’s lease terminations

Kruzynski contrasted Parc-Extension to a neighbourhood like Pointe-Saint-Charles, which had almost 15,000 residents as of 2016. Pointe-Saint-Charles has long been known as a hub of community activism, where grassroots initiatives have achieved big gains and stopped major projects that threatened the social fabric of the neighbourhood.

“It’s more homogeneous than Parc-Ex. Parc-Ex is huge and it has a huge diversity of people, so it’s much more difficult in that type of neighbourhood to have these community commons… that are solid over time. Especially if there’s movement, like people coming and leaving,” Kruzynski explained. “Not only do you have to have the community, but you have to be ready to run a campaign, which involves pressure tactics that start out weaker, like a petition or a demonstration, but you have to be ready to move to the actual squatting of the space, if that’s what it takes (to hold onto community spaces).”

The Carrefour d’éducation populaire de Pointe-Saint-Charles faced a similar situation to William-Hingston: they’ve been threatened with eviction by the CSSDM for years, most recently being served a lease termination notice last July 24, along with the CÉDA in Saint-Henri. Kruzynski theorized that because there’s always been strong community mobilization — with the community occupying the building on the eve of the planned closures before being granted a reprieve — it hasn’t happened yet.

A loss for the community in Parc-Extension

According to Ndjel, Afrique au Féminin normally serves about 5,000 people per year, and between April 2024 and March 2025, they recorded 19,000 visits. “We have a lot of new immigrants that come from Parc-Extension who need help,” Ndjel said.

The organization relies on about 263 volunteers annually.

“If Afrique au Féminin received one family, and the family has many needs, I know that I can take care of one or two needs, and the other needs can be taken care of by the other organizations,” Ndjel said. “It used to be that I accompany them to the door of the other organization.” Now, those doors are one or two kilometres away.

Sepideh Shahamati, a volunteer with the Community-Based Action Research (CBAR), explained that the location was very important.

“Imagine you’re an immigrant and you don’t know the city, and you don’t know where to go, and like that, they could go to one place and they had access to all the resources. And that was really helpful for these immigrants,” said Shahamati.

Ndjel believes the city should have fought harder to keep the groups together.

“I think that if they knew our mission and they knew the work that we are doing in Parc-Extension, they would defend us,” she said. “They don’t understand our mission, and they don’t want to help us.”

For Isabelle Prud’homme, a French teacher and longtime volunteer with CBAR, the change is more than just a logistical inconvenience.

“With CBAR, they used to have meetings in the William-Hingston building,” Prud’homme said. “I wish to talk to (the CSSDM), but they talk to nobody.”

The Rover reached out to the CSSDM for a comment, but did not receive a response.

The CSSDM also evicted over a dozen community groups from a building in Ahuntsic-Cartierville.

Anna Kruzynski played a leading role in the creation of Bâtiment 7, a “social centre that brings together cooperatives and self-managed workspaces.”

In 2006, Kruzynski toured the social centres in Rome, Italy, which inspired the idea to squat in an abandoned building in Pointe-Saint-Charles and make an autonomous social centre out of it. They were able to acquire one of the last buildings on the Lachine Canal that had not yet been transformed into condos.

“We did a campaign for two years… we were expelled 24 hours later by snipers on the roof,” Kruzynski recalls. “Then we decided to join forces with other community organizations… to demand that one of the buildings on the CN rail sites… be preserved and donated to the community for the social centre, which was the campaign that lasted seven years.”

Kruzynski and her team won the building, won $1M for base building, and they opened in 2018.

Bâtiment 7 was years in the making. But it demonstrates what’s possible with community support and organization.

Kaur’s positive experience at William-Hingston demonstrates the larger role it played in Parc-Extension, as both a support system and a place to gather. While her own family is now closer to Afrique au Féminin’s new location, other families aren’t so lucky. These community groups ensured needs were met, with no need to navigate the bureaucracy that often comes with receiving help.

“I made friends there… I learned English, French, and became more confident,” Kaur said.

Did you like this article? Share it with a friend!

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.