A Private Monopoly on Gender-Affirming Surgeries Raises Concerns

GrS Montreal patient testimonials highlight gaps in post-operative care, difficulties accessing care, and limited surgical options.

The only clinic offering gender-affirming surgeries in Quebec, GrS Montreal, has a special agreement with the Ministry of Health, which provides patient coverage but does not fully integrate care into the public system: care is entrusted exclusively to the private company.

While the clinic generally has a good reputation, concerns are emerging: patients are being turned away and financial barriers remain, surgical options are limited, and post-operative care is not always adequate, among other issues.

Community members and experts are questioning the effects of the monopoly: could the clinic’s financial interests compromise the interests of patients? Would it be possible to better regulate care by integrating it into the public system, while also achieving savings?

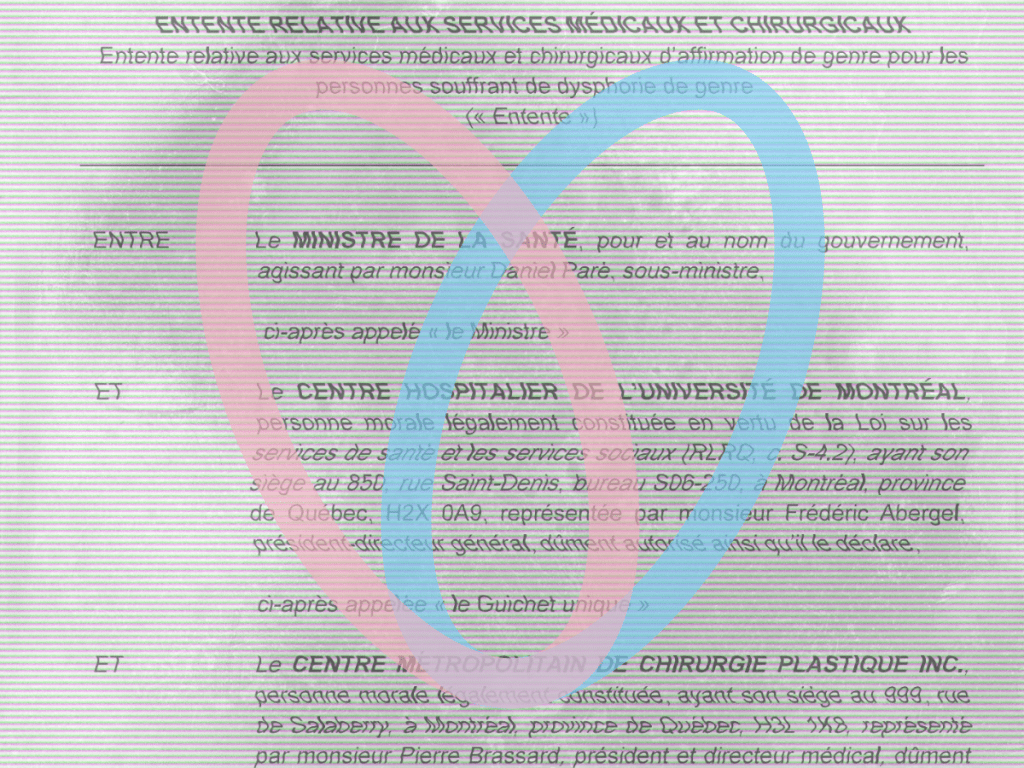

Since 2009, the Centre métropolitain de chirurgie plastique, a private specialized hospital that includes the GrS Montréal clinic and the L’Asclépiade convalescent home, has had special agreements with the Ministère de la Santé et des Services Sociaux (MSSS) and the Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM), granting it a de facto monopoly on gender affirmation surgeries in Quebec.

The agreements were obtained through an access to information request and forwarded to Pivot.

Pivot also collected testimonials from a dozen GrS patients to explore the impact that its monopoly could have on the quality and variety of gender-affirming surgeries offered in the private sector in partnership with Quebec’s public health system.

Although most patients report positive experiences, some negative trends are emerging: several complain of inadequate follow-up after surgery, limited access to care, and restricted surgical options.

“I feel like if GrS has such a good reputation, it’s not because they’re the best, but because they’re the only ones […] There’s no competition, and no one dares to complain for fear of losing their only chance to get the surgeries they need,” says Alexis St-Onge, a GrS patient who underwent a double mastectomy and was disappointed with his post-operative follow-up but satisfied with the care he received and the results.

For Celeste Trianon, a transgender rights activist, this monopoly granted to a private clinic is a problem that harms the interests of transgender people by limiting their options, but also their right to access the best public care available, since GrS is a private clinic that must first ensure its profits.

“Trans people deserve access to the best care, not just one institution with a special contract with the MSSS,” she said.

Indeed, Anne Plourde, a researcher at the Institut de recherche et d’informations socioéconomiques (IRIS), points out that several studies generally show significant negative effects of healthcare privatization in terms of the quality of care and its oversight.

“Privatization of care is not a good thing. The big problem with privatization is the lack of transparency,” she says.

GrS declined multiple requests for interviews and comments from Pivot.

A justified monopoly?

In its most recent agreement with GrS — renewed in 2024 and valid until 2028 — the Ministry of Health makes the clinic the sole provider of gender affirming medical and surgical services on behalf of the CHUM, itself a “one-stop shop” for such services.

The MSSS writes that a “public call for tenders would not serve the public interest,” since it considers GrS Montreal to be “the only provider capable of meeting the desired performance requirements.” The ministry adds that “no other company has come forward to offer the services” and that a contract by mutual agreement can therefore be concluded.

The agreement covers the surgeries themselves, post-operative care, corrective surgeries, medical consultations, and administrative costs.

The clinic bills the CHUM for its services, and the costs are covered by the MSSS based on an annual budget set by the ministry in collaboration with the other two parties, according to a fee schedule established in the agreement.

Patient eligibility is determined by the clinic, while the CHUM reviews patient applications and authorizes funding requests for cases approved by GrS.

Anne Plourde, a researcher specializing in health privatization issues, believes that entrusting care to the private sector is generally not a good thing, as studies show that the quality of care is reduced.

She also points out that data shows that private care costs taxpayers more than if it were provided by the public system. This is because the fees billed to the government include a profit margin, and clinics have an incentive to inflate their costs to increase this margin.

Anne Plourde believes that the government has the power to pressure GrS to require its doctors to join the public service by making funding conditional on their registration with the Régie de l’assurance maladie du Québec (RAMQ) — rather than through a special agreement that circumvents the public system. The clinic could remain private (like a family medicine clinic).

“As doctors in the public system, they would be subject to the various ministry standards that apply to participating doctors, but not to non-participating doctors.”

Isabelle Leblanc, president of Médecins québécois pour le régime public (MQRP), also believes that it would be appropriate for specialists providing trans-affirmative care to join the RAMQ, but also that gender-affirming surgeries should be included in the plan. She believes that this would reduce costs for taxpayers and patients.

However, Isabelle Leblanc is not convinced that joining the public system would improve the quality of care, given the clinic’s good reputation. She raises the possibility that GrS may have entered into this special agreement in order to protect the interests of trans people.

In an article published in 2023 in the Annales de Chirurgie Plastique Esthétique, the GrS team highlights the clinic’s expertise as the only facility in Canada specializing exclusively in gender-affirming surgery and notes that the healthcare system has been slow to respond to the needs of trans people, given the lack of specialized staff and the lack of integration of trans issues into the curriculum of medical institutions.

“With its volume and expertise, GrS Montreal is the largest gender-affirming surgery centre in the world,” the article states. The clinic receives patients from many countries around the globe.

That said, according to the president of the MQRP, “if there were to be an anti-trans political shift, it would be more difficult to end access to trans surgeries if they were integrated into the RAMQ rather than under a special agreement.”

Celeste Trianon, for her part, believes that the monopoly granted to GrS creates a vicious circle that ensures that doctors specializing in trans surgeries will remain in the private sector, thereby hindering the development of expertise in the public sector.

She also believes that the private clinic has no incentive to prioritize the interests of trans people over profit.

“GrS Montreal is an essential institution for trans people in Quebec, even though it is private. But the fact remains that as a publicly-funded institution, it must serve the interests of the community above all else,” says Celeste Trianon.

For its part, the MSSS maintains that it is currently impossible to change the model or develop expertise in the public system. However, the ministry says it is open to revisiting the agreement if other doctors want to specialize in gender-affirming surgery and join the public system, but that this is not the case at this time.

As Trianon pointed out, Isabelle Leblanc agrees that newly formed doctors could be incentivized by GrS Montreal to maintain the monopoly since they are the only ones to offer the services and formations are hard to find elsewhere, thus enabling a vicious circle.

Poor treatment

GrS Montreal has a reputation for providing excellent services overall, in addition to being subject to the same standards, regulations, and laws as any other health service.

However, stories of mistreatment are emerging, and concern is growing within the trans community.

GrS’s marketing strategy, which features testimonials stripped of any negativity on its website, contrasts with the information gathered in this investigation.

Indeed, the “Testimonials” section of the GrS Montreal website (archived here and here) contains only positive comments, in both French and English. One comment in the English section even compares the clinic to a “Disneyland” for surgeries.

The testimonials collected by Pivot are less glowing overall. Some people said they shared their negative experiences with GrS, suggesting that less positive testimonials are indeed being hidden by the private clinic.

During her stay at GrS, Marie* — who requested anonymity for fear of reprisals and to protect her privacy — experienced serious difficulties.

“Everything was going well until it was time to remove the catheter,” she says. A nurse then accidentally cut her urethra instead of the stitches, causing heavy bleeding.

The doctors then wanted to discharge her without removing her catheter, leaving this task to her family doctor when she would return to Ontario a few days later. Marie objected, but the doctors insisted on discharging her.

She feels she was forced to leave the L’Asclépiade convalescent home too early and was likely given inadequate instructions for her recovery, which she says nearly led to her death. Marie suffered daily bleeding for a month after the incident and had to be rushed to the hospital several times.

“I feel like we are left to fend for ourselves once we left L’Asclépiade.”

Despite everything, she says she is happy with the results and explains that the care she received at GrS was good, except for this accident.

GrS is responsible for post-operative care and can request an adjustment from the CHUM to keep patients longer in case of complications or unforeseen events. The clinic is then compensated accordingly.

GrS also has an agreement with Sacré-Coeur Hospital in Montreal to transfer patients in critical condition.

After discharge from Asclépiade, follow-up care is provided by GrS in collaboration with external health professionals who patients may consult.

Trans Patient Union (TPU), a Montreal-based coalition by and for trans people, collects and shares patient experiences to develop better standards of care. Jacob Franklin, founder of TPU, points out that experiences like Marie’s are unfortunately not isolated. “We’ve heard many similar stories,” he says.

“There is room for a lot of improvement on the part of GrS, and that’s why our coalition was formed.”

Several trans people also participate in discussion groups about the surgeries they want or have had with GrS.

These groups have revealed that certain doctors have a not so good reputation for delivering the expected results. One surgeon in particular is known for performing mastectomies that are considered botched, according to Jacob Franklin.

He also reports that, according to GrS patients, surgical corrections are systematically refused, even when medically necessary. This is particularly the case for patients whose nipples become necrotic following a double mastectomy, for example.

Certain minor complications — such as healing problems in the case of vaginoplasties — are reportedly common and not well managed by the clinic during long-term follow-up, according to testimonies gathered by Pivot.

One non-binary person — who considered their surgical results to be very good — told Pivot that upon leaving GrS and Asclépiade, the rest of the healthcare network was ill-prepared to meet the needs of trans people. “I had a minor complication and, unable to reach GrS, I was directed to the emergency room when it wasn’t necessary at all,” they said.

“It’s well known that the healthcare system outside of trans professionals is ill-equipped to meet our needs. There should be a competent service to take over. A specifically trained service that isn’t understaffed.”

Limited offer and access

Several people interviewed by Pivot lament the limited choice of doctors and surgical methods at GrS. For each type of surgery, different methods can have different permanent advantages and disadvantages, and the limited number of options available restricts the bodily autonomy of trans people.

For example, GrS offers only one method for vaginoplasty, namely penile inversion. GrS also offers only two techniques for mastectomy, even though there are many more available.

One patient reported that her doctor, Dr. André Brassard, who is also president and medical director of GrS, warned her that he followed a strict model, both medically and aesthetically, for vaginoplasties. “I don’t do custom work,” he told her.

In addition, several trans people also complain about restrictions imposed by GrS on access to care. Under the agreement with the ministry, GrS is responsible for the “clinical assessment” of requests for care and conducts a “biopsychosocial analysis” of patients in light of international standards, but also its own guidelines.

For example, GrS tends to refuse anyone with a body mass index that is too high or who is otherwise unable to obtain a doctor’s note confirming their good health according to a set of criteria established by GrS.

This is in addition to other requirements that already complicate access to care, such as the obligation to provide a letter from a specialist attesting to the necessity of the procedures.

Another recurring theme in the testimonies collected by Pivot is the financial burden of pre- and post-operative care, even though the costs of the surgeries themselves are covered under the special agreement between GrS and the MSSS.

For example, travel costs and most of the essential equipment needed for recovery are not covered and must be paid for by patients out of their own pockets.

This is in addition to the fact that recovery time prevents patients from working for a period ranging from one to three months, depending on the surgery.

All of this is worrying the trans community, to the point where one trans woman who wanted surgery told us she had decided to give up entirely, having no other choice but to turn to GrS. “There are too many horror stories piling up and I don’t trust this clinic,” she said.

Among the people Pivot spoke to, several are concerned that GrS has an interest in limiting costs, or even maximizing profits at the expense of the quality of service.

For Celeste Trianon, limiting surgical options shows that profit takes precedence over the interests of patients.

“The problem is not that GrS Montreal occasionally has medical accidents, which is inevitable in the healthcare system,” she says. “However, the fact that they are in a public-private partnership with the MSSS, holding a de facto monopoly, but nevertheless trying to use a ‘one size fits all’ approach to patient care — which is contrary to the principles of the Health and Social Services Act — is dangerous.”

Isabelle Leblanc, from the MQRP, points out that by going through the RAMQ, it would be possible to train more surgeons and develop more varied surgical techniques.

“If its doctors joined the RAMQ, it could facilitate access to surgery elsewhere in Quebec by having doctors travel instead of patients traveling to Montreal,” she adds. This would remove the burden of travel costs from patients, who do not always have the means to travel.

Incidents and complaints

The National Register of Incidents and Accidents in Health and Social Services (RNIASSS) shows that reports made by GrS and L’Asclépiade have recently increased by 47 per cent, with 143 reports between April 1, 2023, and March 31, 2024, compared to 97 reports for the 2022-2023 period.

Major complications for gender reassignment surgery are rare, according to several studies, but we do not know the figures for GrS specifically.

The Ministry of Health has not confirmed whether GrS is required to report incidents and accidents involving patients from outside the province.

GrS has a high turnover rate, with no fewer than 1,000 surgeries per year, according to the clinic’s report in the Annales de Chirurgie Plastique Esthétique.

When questioned by Pivot, the Ministry of Health insisted that patients can file a complaint with the CIUSSS du Nord-de-l’Île-de-Montréal or the Collège des médecins if they feel that the care they received was not up to standard. The MSSS specifies that it is also possible to file a complaint with the Ombud if the follow-up or response obtained from the CIUSSS or the Collège is unsatisfactory.

In addition, the MSSS mentions that GrS has received an honourable mention from Accreditation Canada, which accredits health care facilities according to national and international standards. However, Accreditation Canada confirmed to Pivot that it does not have specific standards for gender-affirming care.

According to Celeste Trianon, people who are in poor health following serious situations are not necessarily in a position to file a complaint, while others are afraid or lack the education necessary to navigate these processes.

“It’s clear that members of the trans community, a highly marginalized community, do not have the same means to defend their rights as service users,” she said. ”Addressing this, particularly by building partnerships between the trans community and the entities responsible for reviewing their complaints, is imperative.”

“Patients deserve access to the same quality of care at GrS as anywhere else in the public system. And it should be the job of the ministry, not just the patients, to ensure adequate oversight,” adds Celeste Trianon.

Anne Plourde explains that it is more difficult to obtain information, collect data, monitor service quality, and follow up on private care.

“If the MSSS is shirking its responsibility, that’s worrying,” she adds.

Canadian alternatives

Other facilities offer gender-affirming surgeries in Canada. This is the case for two hospitals in Ontario (in Ottawa and Toronto) and one in British Columbia (in Vancouver), and several gender-affirming surgeries are available in Nova Scotia through the public health care system.

Most provinces and territories in the country allow patients to seek care from GrS through the public system, even if services are available there. However, Quebec does not allow patients to seek trans-affirmative care elsewhere in the country.

Isabelle Leblanc, from the MQRP, explains that integrating gender-affirming surgeries into the RAMQ would allow patients to seek care elsewhere in the country under interprovincial reciprocal agreements on public care, which the special agreement does not currently offer.

The Ottawa Hospital (OH) opened a clinic offering gender-affirming surgeries in early 2024. It specializes in care for medically complex cases, which is not the case for GrS. With access to the OH clinic, trans patients would potentially have more flexibility than what GrS offers.

Elle Alder, a trans woman who lives in Toronto and travelled to Montreal for a vaginoplasty, also explains that information circulating in trans discussion groups suggests that the care offered by OH produces better aesthetic results for this surgery.

However, the wait time is much longer than at GrS.

Alder explains that Ontario’s public health system allows patients to choose between OH and GrS. “I chose to go to GrS because the wait is shorter,” she says.

The MSSS does not consider it necessary to open access to care offered elsewhere in Canada for Quebec patients, since GrS already offers the services here.

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.