Behind McGill Admin’s War on Dissent

A deeper look at how McGill’s administration has criminalized pro-Palestinian protesters over the last two months.

SPVM riot police stand in front of McGill University’s Arts Building after forcing protesters away from the Administration building during a raid on June 6, 2024. The SPVM had been called to campus after pro-Palestinian protestors occupied the university administration building. PHOTOS: William Wilson @williamwilsonphotography

In the early 1980s, a group of McGill students got together to explore the act of divestment.

The McGill South Africa Committee was concerned by the apartheid in South Africa and focused on campaigning for their university to divest from businesses operating in that country. Their work was similar to what we are seeing today at pro-Palestine protests on university campuses across Canada: they wrote letters, campaigned, organized demonstrations regularly, and even occupied university offices until the board of governors agreed to discuss divestment.

After years of protesting and raising awareness, McGill became the first Canadian university to divest from apartheid South Africa in 1985. The decision was a big win for the student groups who continued their work of educating people even after the divestment.

McGill also divested from Burma in 2006, and cut ties with Russian institutions and the Chinese-based company Huawei, all for geopolitical reasons. Most recently, the university also divested from fossil fuels thanks to enormous pressure from community members deeply concerned about the climate crisis. There is precedent for divestment. In fact, it’s well within the realm of possibility for divestment to happen again.

Support Independent Journalism.

All these historical moves were only possible through student protests, continuous effort and pressure on the administration to act responsibly for where they allocate their funds.

But despite McGill’s history of divestment for geopolitical issues, McGill president Deep Saini wrote in his Montreal Gazette op-ed last month that divestment from organizations due to their location would “compromise McGill’s mission and ability to create a healthy, safe environment.”

Saini overlooks the university’s past. McGill has supported international causes that reflect the interests of its community. If divestment has happened before, what makes this time different?

A “misleading” use of language

McGill staff, faculty, students, and alumni published an open letter on June 7 in response to Saini’s op-ed. They call out the “hypocrisy” in his statements and point to the power and value of student movements in making global change. The letter ends by saying that while Saini claims to want to remain neutral, the administration’s silence about Palestine is telling.

The letter was quickly circulated and signed by 210 people in the McGill community. Rine Veith, a McGill alum who signed the letter, said they could’ve had a much larger list of supporters had they campaigned longer, but the goal was to get the letter out as soon as possible.

“It’s been incredibly frustrating to me to see incendiary language in the framing of students, community members, alumni and faculty,” says Vieth. “I was also really frustrated that juxtaposition and facts didn’t seem to matter to the administration.”

In addition to the op-ed, Vieth points to emails from the McGill administration, as well as their official statements on its website depicting the encampment as a violent and unlawful space.

“What is happening at McGill isn’t a peaceful protest; it’s an unlawful occupation,” Saini writes in the Gazette op-ed.

In their own experience, Vieth says this isn’t what they’ve seen.

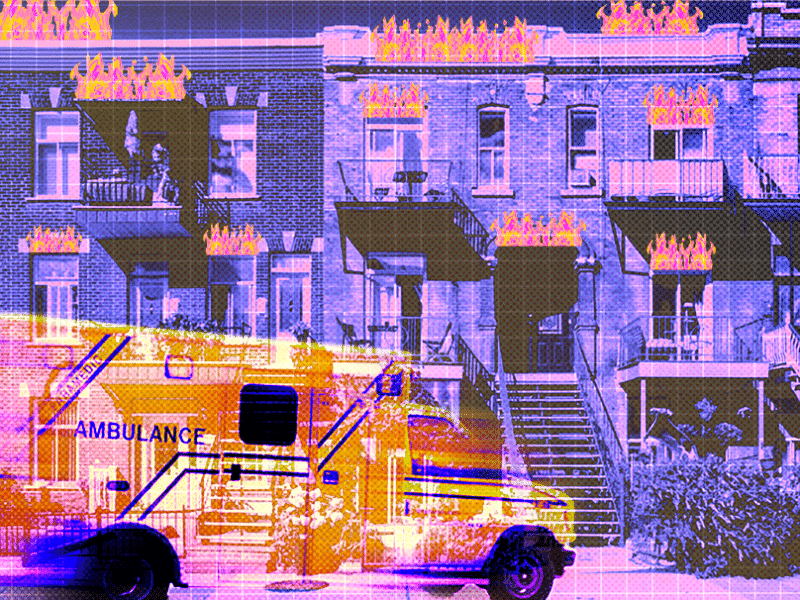

SPVM riot police charged and beat protesters outside of the McGill Administration Building after being called by the university to clear a pro-Palestinian occupation on June 6, 2024. PHOTO: William Wilson @williamwilsonphotography

“I’ve walked by the encampment, I’ve read books next to it; I’ve never seen anyone appear to violently threaten anyone else. This idea of the encampment as a dark, violent, scary space doesn’t seem to match up with my reality,” they say.

Ted Rutland, a professor at Concordia, agrees. He’s been helping out at the McGill encampment nearly every day since it started, alongside about 100 other professors from both McGill and Concordia. The professors gather and distribute tents and camping materials, manage water issues caused by the rain, and even do laundry for the students.

“It’s been a real honour to be able to be there with students from Concordia and McGill primarily who are doing this really bold, principled, and necessary action,” says Rutland.

Rutland explains that he feels enraged by the McGill administration’s official messaging which he says has no relation to the reality on the ground.

In reality, Rutland says that every day, people go to the encampment to make donations or just talk to each other. He says that it’s become a meaningful space for people both politically and emotionally.

“It’s just really magical, I think the way the encampment has become a hub for the broader community in Montreal who are deeply upset about the genocide in Gaza, and the total lack of responsibility taken by our elected officials and institutions,” says Rutland.

But he says that for many people who have never seen the encampment, McGill administration’s official statements and mass emails can be misleading.

Take the example of June 6, 2024, when a group of independent pro-Palestinian protesters occupied McGill University’s James Administration Building. Footage from that day shows a large group of protesters chanting together when police began spraying tear gas and pepper spray, dispersing the crowd. When some protesters tried to stand their ground, police were seen forcibly pushing them back with barricades.

A spokesperson for the Solidarity for Palestinian Human Rights (SPHR) McGill who wished to remain anonymous said the students who occupied the administration building were peacefully protesting to gain more attention to the need for immediate divestment.

The McGill administration called the Montreal police to campus and the subsequent raid ended with 15 protesters arrested. Others (including staff, students, and faculty members) were tear-gassed and pushed to the ground.

McGill’s official statement about the event states that students blocked several entry doors and staff inside the building were forced to shelter in place. “We strongly condemn the use of intimidating, aggressive, harassing or illegal tactics such as those seen yesterday,” the administration wrote on June 7.

SPVM officers advanced on pro-Palestinian protesters, using their batons and pepper spray, after protestors occupied McGill’s Administration building on June 6, 2024. PHOTOS: William Wilson @williamwilsonphotography

A few days later, Academics for Palestine, a Canada-wide network of academics supporting Palestinian liberation, published a faculty eyewitness report of the June 6 incident from McGill and Concordia faculty members who were present. The report focused on correcting several misconceptions about that day, specifically highlighting that those who occupied the administration building were peaceful and non-violent.

“Importantly, when entering the building, students made sure to keep the back door open to ensure the safe and immediate evacuation of the staff… students were intent on ensuring that everyone working in the building could leave freely and indeed before riot police entered, we watched staff come out the back door freely, unimpeded by any of the students,” states the report.

Still, the McGill administration has reiterated in their messaging over and over again that the encampment is not peaceful and threatens the safety of community members. Yet two rejected injunctions, as well as the police’s refusal to dismantle it, suggest otherwise.

The McGill administration ignored multiple requests to provide comment for this article.

“When I receive emails, it seems to me as if senior administration is so detached, not only from students, faculty, staff, alumni, but they’re also so detached from the City of Montreal that they see McGill as this sort of very isolated island within an island. And I just find that really heartbreaking,” says Vieth.

McGill’s proposals are missing the mark, say protestors

Last week, McGill administration announced that they will no longer negotiate with the encampment members and will resort to “disciplinary action.”

This was following the encampment’s rejection of the McGill administration’s last proposal to the encampment.

The proposal listed four main initiatives: that McGill will review their investments through a committee on sustainability and social responsibility, review how they can support Palestinian scholars, disclose their investments under $500,000, and give amnesty to any McGill members who were part of the encampment prior to June 15.

Zeyad Abisaad, general coordinator for SPHR McGill, explains that the language in the proposal deflects the main demands of the encampments. He questions what more the administration needs to “review” of their investments if it’s already made public that the institution invests millions in weapons manufacturers that supply the Israeli military.

“It’s actually coercion. It’s not a true proposal, because we want commitments and not committees. They keep speaking about their board of governors and committees as if these Zionist institutions and bureaucratic systems suddenly will come to their senses if we go through a committee,” says Abisaab.

“Our demands are clear. I don’t know why there is this give and take on these demands,” says Abisaab. “Through this coercive messaging, people forget that our demands are simply not to be complicit with colonialism and genocide. That’s it.”

Protesters clash with police after McGill University called in the SPVM to disperse an occupation of the Administration Building in support of Palestine on June 6, 2024. PHOTOS: William Wilson @williamwilsonphotography

Vieth says they were shocked when they read the proposal, specifically the part about reviewing how the university can support Palestinian scholars. The university’s existing Students and Scholars at Risk program provides emergency financial support for international scholars impacted by conflict. The proposal aims to create a report on how to leverage and support this program for Palestinian scholars by November 15, 2024.

“I do think that the Scholars at Risk program is great. I also know that McGill has acted very swiftly around students and faculty who were impacted by civil war in Syria. As well as most recently in Ukraine,” says Veith.

When the war in Ukraine started, McGill was quick to publicly condemn Russia’s invasion and kickstarted several initiatives to help Ukrainians, including fundraisers, educational talks, and supporting students and scholars. Vieth was part of the group at the time that was working quickly to help Ukrainian students.

“Students in Ukraine who wanted to transfer quickly were able to get expedited university transfers,” Vieth explains. “So there is actually a neat history of supporting scholars who are impacted by incredible violence. And to me, it’s just heartbreaking that it gets kicked down the road to a consultation in the fall when that safety and support is needed now… and we know that McGill can do this.”

Who is considered part of the university?

In his op-ed, Saini also states that “Experience has taught us that maintaining a neutral institutional stance on geopolitical matters best supports — as a whole — our 50,000 members who hold varied political views, represent diverse identities, origins and beliefs, and ardently espouse various causes.”

Vieth says that in many of these official statements, the language suggests that the administration is speaking on behalf of the university “as a whole,” when in reality, it’s perhaps the opinion of “a dozen people in the administration building.”

What’s more, Vieth says, is that the language also incites an insider/outsider rhetoric which isolates the encampment from the rest of the university and community. This outlook ignores the enormous community support the encampment has received in the last two months. It ignores the 210 signatures of faculty, alumni, and students on the open letter to Saini. It ignores over 100 professors like Rutland who have been supporting the encampment since the beginning.

“A university is students, staff, faculty, maybe even as broad as alumni — it’s the people who make it up. And I do think that senior administration should be there to serve the interests of the university broadly, not just their own self-interests,” says Vieth.

Ultimately, they argue that the board of governors calls the shots. Rutland compares modern universities to a hedge fund where the primary consideration is a return on capital invested.

“But it’s a place where people come together. It’s a place where people meet each other, where people learn together, and sometimes they get ideas about how they can act together to make the world better,” says Rutland. “And that’s not what university administrators want — but it’s what a lot of students, staff and faculty end up wanting to do. And the encampment is an expression of that.”

If we see universities as a space for education, that also includes difficult, uncomfortable education. To learn about the injustices in society, to learn about our connection to them, and to learn how to take responsibility in the face of them.

“I can be as grumpy at McGill for certain things as I would like but in the end, I would just really like the place where I spent far too many years doing a PhD to do the right thing,” says Vieth.

You’ve extensively quoted SPHR, an organization that literally supports terrorism. 4 seconds of googling their name would show you that they use phrases such as “Globalize the Intifada”. It’s right there, front and centre, on their Instagram. In an article that focuses so much on language and rhetoric, it’s beyond disgusting that you refuse to focus on the language and rhetoric of the subjects of your own article.

Imagine if, as a journalist working for a leftist, progressive news organization, you quoted a white supremacist whose activism includes phrases such as “Globalize the lynchings!”. You probably wouldn’t exactly want to be associated with a person or organization who explicitly supports murdering Black people around the world, right? But for some reason, an organization that supports and incites murdering Jews around the world, that’s somehow okay? Wtf is wrong with the Rover? How can you possibly be so blind to the hatred and incitement of violence that’s right in front of you?

Great reporting and actions from the community. As a McGill alumni (M.Sc. 2015), I’ve been watching the administration’s responses with disgust. One example that stuck out to me was in Saini’s May 29 update on the encampment, in which he wrote: “Masked demonstrators have targeted personal residences of senior administrators on more than one occasion. At one such event, the protesters stayed for hours, using amplified megaphones to yell ‘you can’t hide’ and other intimidating slogans.”

As anyone who’s been to a protest knows, “you can’t hide” is the first half of a chant that always ends with “you’re supporting genocide” or “we charge you with genocide.” The statement by McGill’s ruling class conveniently omits this.

Source: https://www.mcgill.ca/president/article/communications-messages-community/may-29-update-encampment

RUTLAND LOOOOOL THAT GUY IS FKN CLOWN