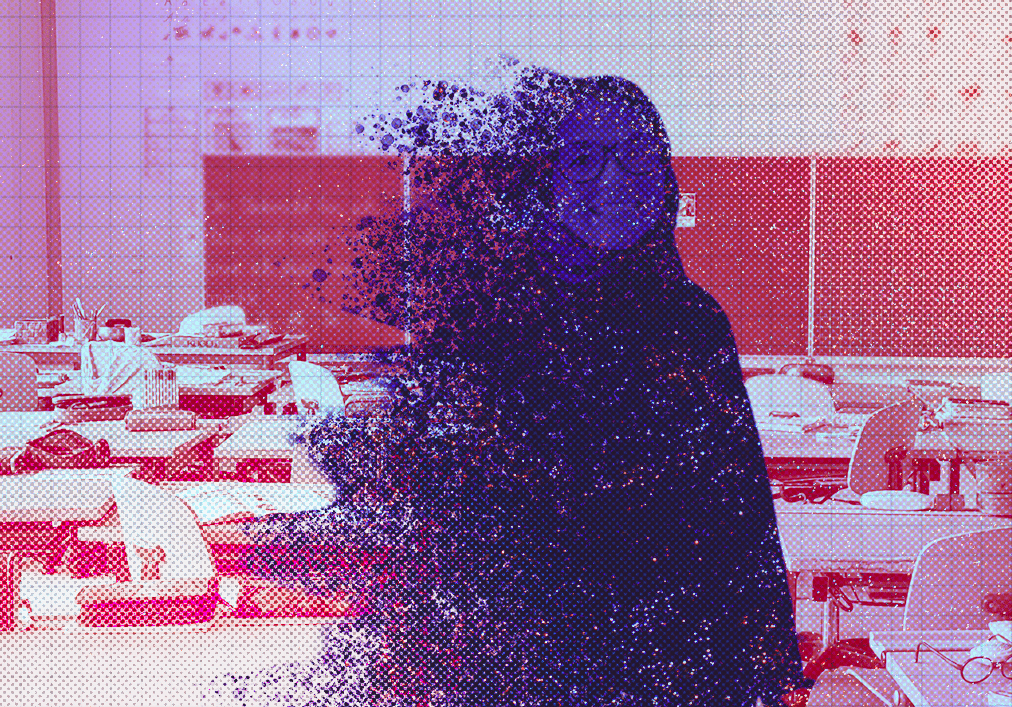

Bill 94 Put Their Teaching Degrees on Hold

Two Muslim women who wear the hijab discuss the moment they learned they could no longer complete their education degrees in Quebec.

Education students Amira Belmadi* and Saloua Salhi* had Monday, Nov. 17, 2025, marked on their calendars, but for different reasons.

For Belmadi, it was supposed to be her first day as a teacher trainee in a Montreal elementary school. She had met her soon-to-be students and their professor in preparation for the traineeship. She had mixed feelings — she was excited, yet worried about what this new beginning held for her, and what the children would say about their newest teacher.

At the same time, in another part of the city, Salhi was studying for her exam, scheduled on that day.

But just three days before, they met the same fate. An email notification from their faculty brought everything to a halt.

Citing Bill 94, which reinforces secularism in the education sector, the email said that any person called upon to provide any service on behalf of the Montreal School Service Centre (CSSDM) must comply with the legislation, prohibiting all staff and volunteers in public schools from wearing religious signs.

The bill was passed last October by Quebec’s CAQ government and is considered to be an extension of Bill 21, which bans religious symbols worn by some state employees, like teachers. Under this new law, the ban on religious symbols in schools has been expanded to include support staff — janitors, secretaries, school psychologists, and interns.

Support your local indie journalists

Belmadi and Salhi both wear the hijab, and we’ve agreed not to publish their real names out of concern for repercussions for speaking out against provincial legislation.

“Nobody saw it coming,” said Belmadi. “They basically dropped the bomb, and then after, we didn’t get any follow-up.”

Most faculties of educational sciences require students to complete internships in schools to earn their degrees. This is the case for both Belmadi and Salhi, who are now restricted from doing them under the new law.

When Belmadi received the email, she called her internship supervisor, pacing her room in distress. “I called them, I was crying, I told them that I didn’t understand the email.”

“Sure, I can’t be employed as a teacher, and I already knew that, but at the very least, they should let us finish our internships.”

The blow was just as personal for Salhi. “It feels like we want to exclude me from Quebec society, as if I didn’t belong, that I didn’t deserve to work in the public sector.”

Dreams interrupted

Although no demographic data is available yet on Bill 94, Statistics Canada’s 2021 census shows that the biggest religious minority in Quebec are Muslims, who represent 5.1 per cent of the province.

A 2022 study by the Association for Canadian Studies showed religious minorities feeling increasingly alienated in the province.

Lead researcher of the study, Miriam Taylor, shared her insight on the links between Bill 21 and now Bill 94, arguing that both laws stem from the instrumentalization of people’s anxieties in the name of values such as neutrality.

“That’s why I wanted to do that research (…) In the name of so-called neutrality, look at the opinions that people have of religious groups. They’re not equal,” she said.

Her research survey also shows disproportionate rates of negative views of religions among Quebecers, with Muslims, the hijab and Islam being the most negatively viewed.

Taylor believes that Bill 94 will only help reinforce people’s prejudices against religious minorities, especially Muslim women.

“Laws are normative. So when seatbelts came into law, people started understanding the importance of seatbelts (…) I think Bill 21 (and Bill 94) normalized this idea of a very false secularism, but it is touted as secularism,” she said.

“We’re putting a target on the back, particularly, of vulnerable, marginalized women (…) who have kind of become the target of this scapegoating.”

Both Belmadi and Salhi were aware of the risks they were taking when they first entered the faculty of education at the French-speaking Université de Montréal in 2023. Yet, both young women had their personal motivation to become teachers.

“It was truly an illumination, I told myself, ‘Ok, this is really what I want to do,’” she recalled.

Belmadi said she wanted to study education since secondary school, having been inspired by an English teacher of hers.

For Salhi, coming from a family of professors, the choice was clear. “I think I inherited that passion because on my mom’s side of the family, they are all French teachers,” she laughed.

“But now I can’t even finish my bachelor’s, knowing that I’m a year and a half in … it shocked me,” said Belmadi.

What’s next?

For both women, the implication of Bill 94 goes beyond their traineeships. “I believe it emboldens people to make it known that they don’t want us here, and it pressures us into making difficult choices,” said Belmadi.

One of those choices for her is between her religious expression and her career — a dilemma that leaves her questioning whether to stay in the province.

“I have two solutions, either I leave for Ottawa, and then I get classes credited… my second option is social work.”

This feeling is also shared by Salhi, who admitted she has begun reconsidering how to become a teacher without going through Quebec’s system.

“I have come to a point where I am thinking of crossing an X on Quebec… We’ve actually reached that point.”

And according to her, they are not the only ones. “We are many who have already started looking at continuing our studies in Ontario,” she said. “It is an idea that is lingering in the mind of many of us.”

Possible economic impacts

Yasser Lahlou, the National Council of Canadian Muslims’ (NCCM) communications and government relations representative, described some of the economic problems that can be engendered by Bill 94:

“At the beginning of the year, we learned that around 5,000 spots were to be filled in the public education system in Quebec, and now we come with legislation that will reduce the number of possible candidates or employees,” he said.

There is no available data on the economic impact of Bill 94, but Lahlou contrasts it with the research and data available on Bill 21. “The amount of economic loss in Canadian dollars to Quebec’s economy caused by Bill 21 is in the billions,” he says, referring to a study on the impact of Bill 21 on Muslim women in Quebec.

The study’s data show a growing desire among Muslim women to leave the province and find employment elsewhere, with around three-quarters of the women surveyed having applied for or considered work outside Quebec. The study estimates the losses related to the emigration of Muslim women from Quebec to be $3.2 billion.

Lahlou fears similar effects with Bill 94. “There is a clear social loss,” he said.

“The economy, inflation, the unemployment rates, and I can name many more — these are the real issues that Quebecers are facing today.”

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.