By and For: Exhibit Traces History of Sex Worker Resistance

Sex worker support organization Stella wants to change the public’s perception of sex work with an exhibit at the Centre des mémoires montréalaises.

More than a century ago, two women met in Montreal’s Red Light District.

In 1915, Maimie Pinzer opened a house for sex workers called the Montreal Mission for Friendless Girls, and it was there that she met Stella Phillips.

“(Maimie) talks in the papers of Stella as this most beautiful, most amazing woman. She speaks about her quite intimately, and so when the sex workers in 1995 were trying to come up with a name for the organization, they said, ‘We should call it Stella, a friend of Maimie,’” says Jenn Clamen, Mobilization and Communications Coordinator at Stella.

Today, their friendship endures through Stella, l’amie de Maimie, the organization named in their honour.

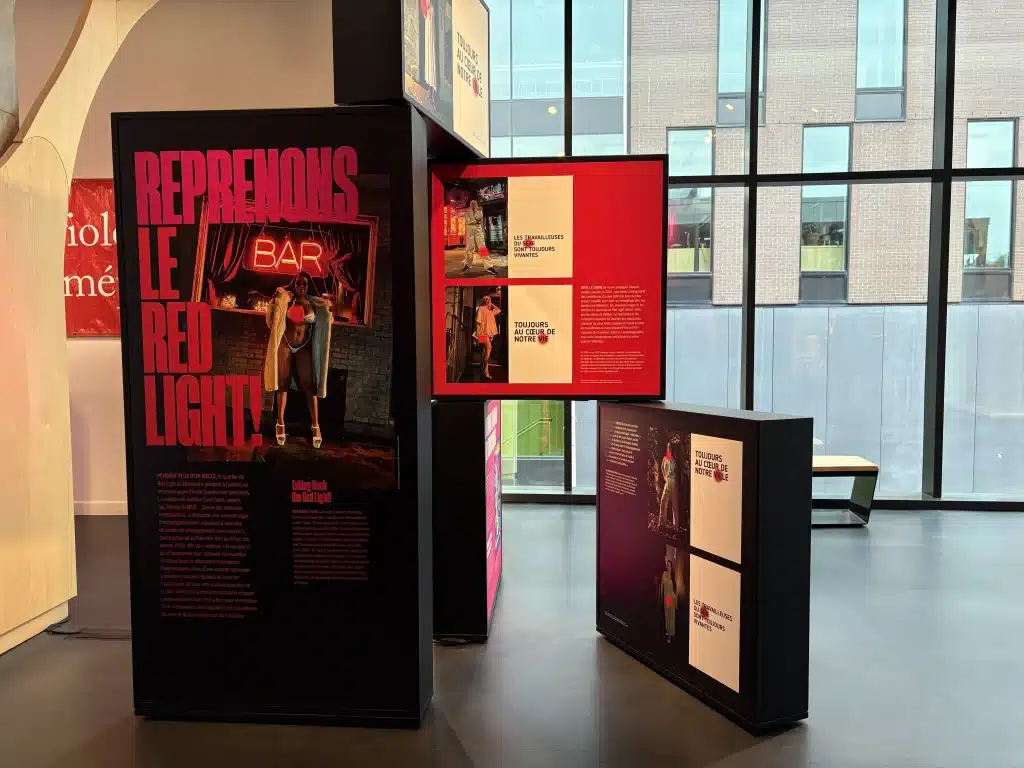

From now until March 15, the Centre des mémoires montréalaises (MEM) presents By and For: 30 Years of Sex Worker Resistance. This multimedia exhibit serves as a living archive, showcasing the sex workers’ rights movement in Montreal.

Stella, a network of survival and solidarity

At Stella, sex workers determine their own goals, and Stella offers them the tools to achieve them.

“We are there to support sex workers in whatever they want to do. People want to leave the industry. People want to start working in the industry. People hate their job, they love their job. It doesn’t matter for us,” Clamen said.

Stella makes an average of 8,000 contacts per year with sex workers across the island of Montreal. This happens in the workplaces, on the streets, or in Stella’s office space. The organization also gives out an average of 160,000 condoms a year, a basic but essential form of harm reduction.

Support your local indie journalists.

Sandra Wesley, the Executive Director of Stella, emphasizes that the organization is part of a broader movement that challenges how society views sex work.

“People have a very voyeuristic and sensational idea of sex work, and they don’t necessarily realize that we’re also a political movement, that the work that we do is very serious, not particularly sexy, and that sex workers’ rights are relevant to all kinds of social movements,” Wesley said.

This grassroots organization has had a huge impact on Canada’s legal landscape surrounding sex work. In 2013, Stella intervened at the Supreme Court for the Canada (AG) v. Bedford case, which struck down Canada’s old laws, ruling that they infringed upon sex workers’ right to security as outlined in Section 7 of the Charter.

But in June 2014, the Harper government introduced Bill C-36, the Protection of Communities and Exploited Persons Act (PCEPA), which re-criminalized sex work under a new legal framework.

“(PCEPA) defines all sex work as inherent exploitation,” Wesley explains. “The mere existence of sex work, based on Parliament’s analysis, is victimizing women and children… so we are defined as exploited persons, and the community is the real victim of the existence of sex work.”

In response, sex worker groups created the Canadian Alliance for Sex Work Law Reform and, in 2017, the Alliance published a document outlining the recommendations for legal reform. All of the legal analysis and arguments were developed entirely by sex workers.

“We went from just saying, ‘We want decriminalization’ to ‘Here’s the exact bill that we want passed and all of the justification,’” explains Wesley.

In 2021, the Alliance launched a national Charter challenge against PCEPA — a collective effort led by 25 organizations, including Stella.

The exhibit

The exhibit tells Stella’s story of resistance and how it has always been intertwined with the fights of other social movements. Marginalized groups face many of the same struggles — stigma, policing, harassment — and they’re fighting for the same goals: safety, justice, autonomy.

A wall of plaster cast breasts. A blanket decorated by female prisoners in the now-closed Maison Tanguay. A pink room filled with sex workers’ personal items.

Stella set out to showcase the collective experience of sex workers in Montreal. Wesley explains that the personal testimonies of sex workers can trigger some extremely emotional responses, and often those stories will be used against them.

“We find it really important… to showcase the stories of sex workers who have the ability to tell that story in an interesting way,” Wesley adds.

So the exhibit organizers got creative.

Visitors won’t see the faces of sex workers, but they can see plaster moulds of their breasts hanging from the wall, individual and unique, like a portrait. Visitors won’t see the names of sex workers, but they’ll learn about them through direct quotes and sift through their personal belongings in the pink room.

“I still have the roses he gave me as a reminder of the sweetness that exists in everything I do, sweetness that so many refuse to see,” reads one quote.

“I worked in Toronto, and in parts of Ontario, strippers are required to be licensed. You get this license by going to a government building east on Eglington, where you sat in a room waiting with cab drivers, who were also trying to get licenses. I’m not saying it was obvious who was there for what, but you could definitely make a game of it while you were waiting,” reads another quote.

It makes sense for Stella to have chosen the MEM to host their exhibit — the museum is situated right in the heart of what once was Montreal’s Red Light District. And even though the Quartier des spectacles is branded as a tribute to the Red Light, sex workers were displaced from that area and their work was criminalized; the neon nostalgia splashed across Montreal’s official tourism website is for show.

The city doesn’t get credit for supporting sex workers, but here’s who does: the HIV/AIDS community, migrant justice movements, Jewish communities, Indigenous communities, LGBTQ+ groups, and homelessness organizations.

The exhibit tells Stella’s story of resistance and how it has always been intertwined with the fights of other social movements. Marginalized groups face many of the same struggles — stigma, policing, harassment — and they’re fighting for the same goals: safety, justice, autonomy.

“Most sex worker rights organizations in Canada that were born in the 80s, 90s came out of the HIV movement,” explains Clamen. “Sex workers were named as one of four groups that were vectors of disease… and because of that, sex workers couldn’t get access to health resources the way that they needed.”

Even today, Stella continues that fight, ensuring sex workers can access the services they need.

“Having organizations like Stella and other groups like us across Canada is huge. It’s the idea that we could be here for 30 years, be funded by the government and be able to openly support sex workers, openly give services to sex workers, even just openly being able to give condoms to be used in criminal activity,” says Wesley.

“The fact that when I meet a sex worker who tells me about something horrible that happened to her…” says Wesley, “I actually have the power to do something. I can write a brief to Parliament. I can call someone, I can make sure that her needs are integrated into our political demands.”

It is clear that there is a need for sex workers. There always has been an available service since the beginning of time. So many people feel lonely and in need of that type of companionship and are unable to meet that need for various reasons. It is an important service for those not wanting to invest in a ‘typical’ relationship because of life circumstances, or any other of the 100’s of reasons. Can this also possibly help reduce sexual violence? perhaps … having a regulated service with support for the sex workers is the least that can be done. When they are safe then the clients are also safe. After all we are all conscenting adults!