Housing Crisis: What Is the Ultimate Solution?

During the 2025 federal election, we heard a lot about the problems surrounding the housing market, but only about one solution: “Build More.” Is it really that simple?

Moving day has just passed, and as thousands settle into their new home, there is a growing number who find themselves on the threshold of being homeless.

The cost of housing has nearly doubled across Canada in the past decade. Meanwhile, there has been a 33 per cent increase in Montreal’s unhoused population between 2018 and 2022, reaching 4,690 people according to a study by Centraide of Greater Montreal.

Experts say the lack of affordable housing is a major factor driving people onto the streets.

Hussein left Kuwaït for Canada after the Iraqi army invaded the country in 1990, and he chose Montréal to start fresh. Hussein then moved to Toronto in 1998 for a major promotion, until he finally returned to Montréal in 2023, full of hope.

Support The Rover: we get results!

“I came back to Montréal with the best memories of it,” said Hussein. “This is where I started my life in Canada. I had two of my children here. I have never felt like I wasn’t welcome here. My family is proudly francophone because of my francophone education, and I’m a big advocate for the French language.”

Despite medical problems, including his struggle with diabetes, a recent cancer diagnosis and an ischemic stroke that affected his ability to work and bring home an income, he considered himself lucky to have found a one-bedroom apartment for $950, where he was also on great terms with his landlord.

All that changed last July when the building was sold to new owners who increased the rent from $950 to $1,500. He claims they harassed him because he couldn’t pay. This ordeal and his worsening physical health took a toll on him.

“I even attempted to commit suicide twice,” he said. “I was in an extremely dark place at the time.”

After searching for a new apartment for months, L’Office Municipal d’Habitation de Montréal (OMHM) finally contacted him and told him they had found a home for him at a low-income housing building.

“I thank the OMHM every day,” Hussein said. “They saved me.” He was weeks away from either being homeless or having to depend on his children to help him financially.

Why are people like Hussein facing the threat of homelessness? Will Prime Minister Mark Carney’s “Building Canada Strong” housing plan really help Canadians?

The Supply and Demand Argument

During the federal election, Carney promised that a Liberal government would build 500,000 homes annually through a new Crown corporation, Build Canada Homes (BCH).

This declaration presented building as the only solution to stabilize the price of homes, but what about the price of rental units that push people like Hussein closer to the street? Is building more what Canadians really need?

Even though vacancy rates have reached over 2 per cent in cities like Montreal and Vancouver, with a 3 per cent vacancy rate being a sign of a healthy rental market. So why are rents increasing at a historic rate just the same? Experts disagree on the cause.

The supply and demand argument has dominated public discourse surrounding the housing crisis. But to assume that building more will result in landlords lowering rents seems optimistic, especially in big cities like Montréal, where land for new housing is a finite resource. But if supply goes up, will demand (and prices) come back down?

Ricardo Tranjan, a political economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) and author of the book The Tenant Class, is an expert on the housing crisis and points out these contradictions.

One of the main takeaways from his book is that the supply and demand argument overlooks landlords’ decision to increase rents for profit. He attributes the rising vacancy rates to landlords preferring to leave units vacant rather than lowering rents based on market demand for affordable housing.

In an interview with The Rover, he also explained that cyclical factors like immigration or high interest rates are often used to justify the lack of affordability because “they avoid addressing the fundamental inability of the housing market to deliver affordability.”

“You have to hold on to the idea that if the market worked as it should, it would deliver affordable housing,” he said. “At any given year, you’ll be able to find one or a couple of cyclical factors to explain why the market didn’t deliver affordability,” instead of questioning the market itself.

Véronique Laflamme, spokesperson for the Front d’action populaire en réaménagement urbain (FRAPRU), considers the supply and demand argument to be an oversimplification of the housing crisis.

“There’s a big disconnect between what is being offered on the private market and renters’ needs,” she said.

Faiz Abhuani, founder and director of the non-profit organization Brique par Brique, which has just begun construction on its first social housing project, also considers the supply and demand argument irrelevant when it comes to big cities like Montréal.

“For big cities, it isn’t really a question of supply and demand because we already have vacant housing,” said Abhuani. “I think that there are certain economic factors that make real estate promoters not want to build truly affordable housing.”

So, why is the supply and demand mismatch often presented as the main reason for the lack of affordability?

Tranjan said that this argument is maintained by “a powerful coalition” of three forces.

“There’s the orthodox economists who believe in free markets and refuse to take into account the specificities of the housing market,” he said. “There’s the whole real estate industry who directly benefits from the supply and demand argument through financial incentives (…), and finally the political parties and politicians, because the ‘build more’ argument is more comfortable in the sense that it prevents them from having to use regulatory powers.”

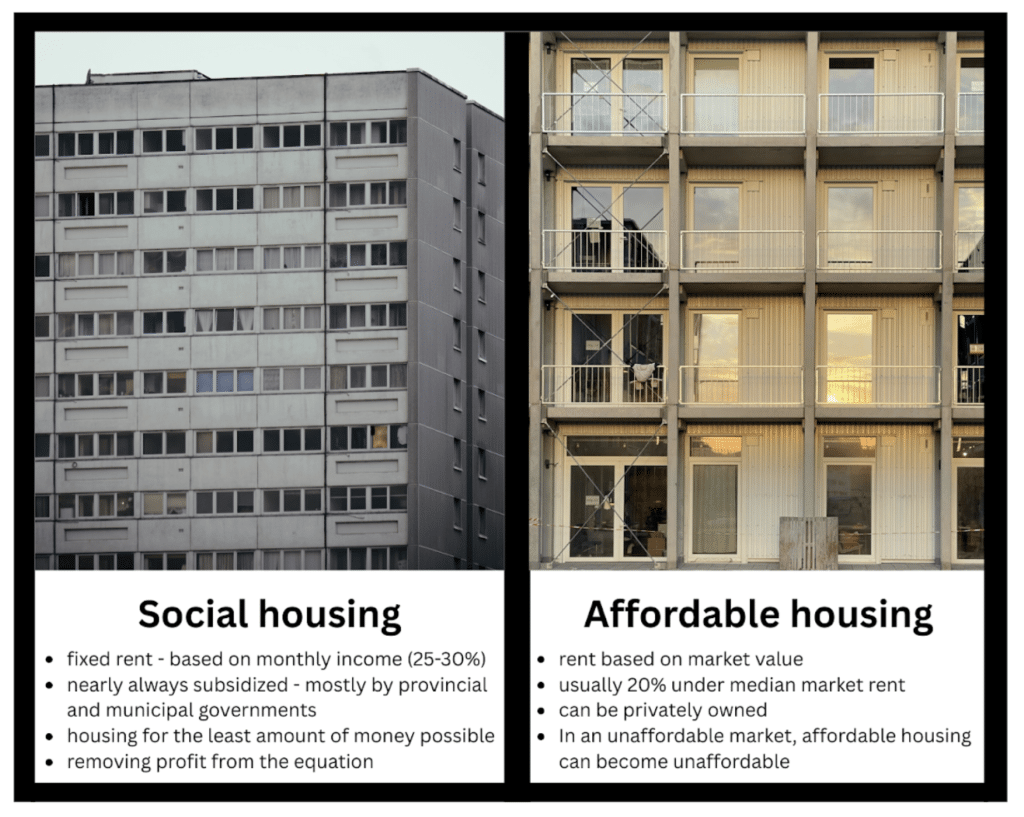

Tranjan says that because the supply argument simplifies the housing crisis to the extent of “we need to build more,” most solutions focus on financial incentives for developers based on the assumption that it automatically translates to lower costs for renters, instead of higher profits. He believes that removing profit from the equation by building more social housing — also called community or non-market housing — is the first step to affordability.

“The biggest misunderstanding is that we only need economic solutions, and not a political response,” he said. “A political response would be the advancing of an alternative way of thinking in building and delivering housing, that removes profit from the equation. That would be a political response.”

The Absence of Social Housing

In 1993, the federal government transferred the responsibility for building social housing to the provinces and territories, while also reducing its funding to them.

Québec and British Columbia created their own social housing programs — which were eventually replaced with affordable housing programs — while the other provinces and territories passed this responsibility on to municipal governments.

Building social housing is now a shared responsibility that is often set aside or avoided. This led to a now historically low number of social housing in Canada of 3.5 per cent of the market compared to 14 per cent in France and 16 per cent in the United Kingdom.

Regarding social housing, Laflamme shared the FRAPRU’s anxieties concerning the Liberal housing plan. “We feel like Mr. Carney is intentionally playing with words, so it’s difficult to know if his plan will make a real difference,” she explained.

The $6 billion in funding to “deeply affordable housing” mentioned in his election platform could be a gamechanger, she said, but it hasn’t been made clear if “deeply affordable housing” refers to social housing or the same affordable housing projects that aren’t really affordable.

The Rover inquired about “deeply affordable housing” and Housing Infrastructure and Communities Canada (HICC) responded that “while there is currently no standard industry definition of deeply affordable housing, the term generally refers to low-cost, below-market housing that is affordable to lower-income households.”

This response at least clarifies that the goal is to provide below-market housing, but it remains unclear how, especially in large cities where land is a finite resource.

HICC also added that social and community housing is “one of the models that can provide deep affordability,” but it did not confirm that social housing will play a role in its plan to provide affordability. As Laflamme told The Rover, it is still unclear what Carney’s minority government is actually planning.

Laflamme’s other concern is that the Liberal housing election platform doesn’t specify which projects will receive subsidies and which projects will get loans. HICC did not respond to our questions about this distinction. If social housing projects are funded with loans, they could end up having to finance these loans through higher rents, despite being non-market housing.

Abhuani also said that social housing is the best way to deliver affordability, but he doesn’t believe that the housing crisis can be solved by the federal government.

“It’s really at a municipal level that things must change,” he said, because of the multiple municipal laws and zoning issues that complicate the process of building social housing.

Red Tape: Zoning and Municipal Laws

Politicians tend to address these obstacles as “red tape” that needs to be cut to make building easier and more affordable — delays in obtaining building permits, restrictive urban planning regulations (zoning), high municipal taxes and municipal laws that prevent building under specific conditions.

While discussing the impact of zoning and municipal laws, Erkan Yonder, professor of Real Estate Finance at Concordia University, explained that for the rental market to be healthy in big cities like Montreal, Vancouver and Toronto, “the amount of rental units being built needs to go up by five to 10 times,” which is no easy feat. To achieve such a level of building, he said that zoning issues must be addressed to facilitate building and encourage investments in the housing market.

“The only way to help the rental market in cities like Montréal, where supply is limited and inelastic, is to address zoning issues to add new supply,” said Yonder.

These issues do make building harder, but a study by the Institut de recherche et d’informations socio-économiques (IRIS) found that bureaucracy and red tape aren’t the main obstacle to affordability, but rather a lack of will from private developers to build affordable housing.

Making building easier or less expensive for private developers does not automatically result in lower rents, according to Tranjan. He views these arguments as excuses to push for fewer regulations surrounding the real estate industry, using the metaphor of “cutting the red tape.”

Most discussions surrounding the housing crisis revolve around regulations.

The FRAPRU advocates for rent control regulations, while construction companies ask for fewer building regulations, and private developers want fewer financial regulations. Based on this, Tranjan describes the housing crisis as a political class war, where each regulatory decision can sway in favour of renters or landlords.

For example, Abhuani said that “asking for government subsidies to build social housing is unrealistic,” so instead he advocates for preferential zoning for off-market housing to allow organizations like Brique par Brique to compete with private developers. This perspective highlights Tranjan’s view of regulations as a political lever that can help certain people but also disadvantage others.

The Rover asked HICC if the use of regulatory powers was part of its housing plan to deliver affordability, but did not receive a response.

In a city like Montreal, where more than 60 per cent of people are renters, households are frustrated with the lack of rent regulations and the difficulties in protecting tenant rights. Obtaining an audience with the Tribunal administratif du logement can take months, and even up to a year for less urgent cases, while renters struggle to make ends meet. In most of Quebec and Canada’s rural areas, a majority of people are homeowners, so the political will to regulate rents isn’t there.

Because of this contrast, it’s important to remember the huge amount of vacant space in Canada. Yonder mentioned this and said that he believes “the best solution to the housing crisis is building new economic regions to ease the demand on cities such as Montréal, Vancouver and Toronto.”

Abhuani, meanwhile, has a similar perspective.

“Mark Carney has a vision of better colonizing Canada, of opening new borders up north, building new cities, and building new roads to better occupy the Canadian territory. He wants to hit two birds with one stone,” Abhuani said. “We’ve reached a point where we can no longer cramp ourselves in Toronto, Vancouver and Montreal”.

Did you like this article? Share it with a friend!

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.