Is Montreal’s Club Scene on Life Support?

Artists and venue owners are worried the city is losing the very things that make up its charm: affordable costs and a thriving cultural scene.

Artists and venues are sounding the alarm about a suffering cultural scene in Montreal. PHOTO: Lou Seltz, @lou.celsius

Montreal’s nightlife is internationally renowned.

But artists, venue owners and dance floor aficionados fear it’s on its way out.

It’s no secret that rent prices are skyrocketing in Montreal, seemingly following in the footsteps of Toronto and Vancouver. Combined with the overall increase of the cost of living, creatives say they fear the will be pushed out of the city. On top of that, small venues have had to contend with hefty noise fines, sometimes leading to their demise.

“The reason people come to Montreal is dying,” Vicky B. Ouellette, an artist and art curator told me over a loud DJ set in Casa Del Popolo’s small concert space. She’s also the co-founder of Studio ZX, an organization that showcases marginalized artists.

I spoke with some of these people at the March edition of Collide, an underground nightlife networking and advocacy event series organized by FANTOM (Fédération des arts nocturnes de Montréal) and Studio ZX. FANTOM does advocacy work and research with after-hours artists, workers, and organizers.

Ouellette said Projet Montréal, Montreal’s current municipal administration, is “investing money and time in looking good in the public sphere and seeing [nightlife] as something to conquer rather than something to empower, something to support, something to fund.”

Mathieu Grondin is the director MTL 24/24, an advocacy group that has hosted all-night parties sanctioned by the city as “pilot projects.” Grondin said it’s getting harder to be an artist in Montreal with the incessant increase in the cost of living.

Support Independent Journalism.

“A lot of the culture we had in Montreal came through these Canadian artists that came to Montreal, [where] they could have a barista job and still play with their bands, and they became Arcade Fire, you know?” said Grondin. “So if we don’t have that, what are we going to have left? We’re going to be a Toronto that speaks French. Who’s going to be interested in that? We’ve got to fight for that. We’re going to fight to keep this uniqueness we have in Montreal.”

Pierre Carrère, who is writing his thesis on Montreal nightlife, said the underground scene is a safe haven for communities in need of protection.

“One thing that comes [out] really often in my thesis and my interviews is the intimacy [of Montreal nightlife], an intimacy that you can’t find in bigger cities like New York. […] Here in Montreal, it’s really more about communities, and it’s so important for me and for a lot of people, more than the music sometimes,” said Carrère.

Oliver Philbin-Briscoe of FANTOM, who grew up in Montreal, said it’s getting harder to access the city’s nightlife, and, by extension, find community.

“I think what a lot of people are fighting for is just having a space that they can go to where they feel as comfortable as the person who’s making $90,000 a year going to the wine bar,” said Philbin-Briscoe. “I want everyone to have access to their version of that experience, whether it means like being up until seven in the morning or going to a screaming punk show by the side of some train tracks. I want everyone to have access to that because essentially it’s just having access to community.”

Le Projet de politique de la vie nocturne

At Collide, Grondin gave an info session on the city’s proposed Projet de politique de la vie nocturne montréalaise and the recommendations in MTL 24/24’s full-length report submitted to the city.

The Projet was published in January, on the heels of Mayor Valérie Plante’s announcement that MTL 24/24’s funding would not be renewed.

This project came after three years of consultations with organizations like Tourisme Montréal and Culture Montréal, and the Creative Footprint Report outlining the underground nightlife community’s expectations.

The March edition of Collide, an underground nightlife networking and advocacy event series organized by FANTOM, at Casa del Popolo. PHOTO: Emelia Fournier

Devoid of concrete policies, it states the city wants to revamp its nightlife regulations, including its noise complaint policy, “extend and develop Montreal’s nights” with 24-hour nightlife boroughs and permits, and figure out how nightlife and residents can “cohabitate.” The policy will be announced next week.

Grondin told Collide attendees the overemphasis on “cohabitation” and economic benefits leaves the project rudderless.

“Normally, there’s a preamble that says why we’re doing this policy. The safe way would be to say for them, ‘Well, nightlife has always been part of the DNA of Montreal.’ That would be the context. ‘We want to save this DNA!’”

Cohabitation or gentrification?

With all of its emphasis on cohabitation, Montreal’s nightlife project makes no mention of gentrification, rent increases, or the imbalance of power between landlords and tenants — and mentions the word ‘artist’ only once.

Projet Montréal does not mention access to housing at all in their Politique sur la vie nocturne. FANTOM raising the alarm of access to housing to preserve art. On top of a housing supply crunch, the recent passage of Bill-31 allows Quebec landlords to unilaterally refuse their tenants’ ability to transfer their lease to another person. This allows landlords to terminate the lease and list the property for a higher rental rate on the market. Philbin-Briscoe said that rent increases push artists out of Montreal.

“Affordability or access to space, that’s the number one concern,” said Philbin-Briscoe. “Way more than anything about being able to sell alcohol at certain times. It’s really about making sure that spaces can continue to exist, and that we’re able to open them or operate them in areas of the city that are still affordable while they’re still affordable, because that’s very precious and already under a lot of threat,” he added.

Carrère said that by ignoring the issues of skyrocketing living costs, the city is “promoting this cultural vibe, but killing it at the same time.”

Artists whan the City of Montreal’s nightlife policy to secure the fate of Montreal’s internationally-acclaimed cultural scene PHOTO: Emelia Fournier

“At the end of the day, it’s the responsibility of the state and of the economy. (They are) permitting investors to buy up housing and speculate. That’s the main problem. Artists don’t have a responsibility there. It’s about protecting the housing of people, it’s about protecting the culture of people,” said Carrère.

Agent of Change

Other cities, like Toronto, London and Melbourne, have protected venues from noise complaint fines by adopting the agent of change principle. That means that new buildings in the neighbourhood must adapt their constructions to their surroundings and be responsible for their own soundproofing. This is a key policy that could already be adopted to protect venues from exorbitant noise complaints is the agent of change principle, says Grondin. After all, it’s a policy that has worked in other cities, he points out.

Grondin said the agent of change principle concept has been brought forth to Montreal through the Creative Footprint Report and public consultations, yet was absent from their Projet de vie nocturne.

Philbin-Briscoe says he’s seen dozens of venues shutter due to noise complaints over the years, and more are sure to follow as the city dawdles on policy-making.

“You’ve got these cultural creative hubs that are meeting places for dozens or hundreds of people and one person’s able to take that all away, which is, to me, such a bizarre power dynamic to exist in a city, right? It doesn’t really make sense,“ he said.

Currently, any resident of Montreal can make a noise complaint at any time of day. There is no pre-determined allowable decibel level, and it’s up to the discretion of the police officers who respond to the complaint whether a fine will be issued, which can range from $1,500 to $12,000.

This dynamic was exacerbated by new tenants moving in during lockdown while venues were shuttered, leading to an increase of noise complaints when they reopened. As reported in The Rover, this exact scenario happened to Turbo Haüs, a St-Denis St. club that brings in hardcore and punk bands from across North America.

Closing time

While most people I talked to are supportive of the city offering 24-hour liquor sale permits for specific venues or events, they were unanimous in saying that creating designated 24-hour “nightlife zones” would create more problems than it would solve.

“By making a zone, we will concentrate all the problems. It can be turned against us,” said Grondin, who also fears that venue rent increases would skyrocket in 24-hour zones.

Attempting to consolidate all late-night permits to a single neighbourhood, bringing together the “mainstream” crowds also poses dangers for queer people, said Ouellette, who is a trans woman.

“Montreal nightlife has always been a sanctuary of freedom for me, both for artistic exploration and identity exploration,” she said.

PHOTO: Lou Seltz, @lou.celsius

Ouellette said allowing certain spaces to remain open past 3 a.m. in different parts of the city could prevent dangerous interactions that occur when all the bars let out at the same time.

“It’s been years since I’ve faced direct violence on the street, but it’s something I’ve witnessed many times, and I’ve heard ten times more stories about people who have experienced verbal and physical aggression after the bars close at 3 a.m. When you have everyone leaving the bar at the same time, drunk people yelling transphobic and homophobic slurs, that super dense exodus of drunk people from bars makes that worse,” said Ouellette.

‘Not a cent put on the underground scene’

Grondin also suggested that tourism revenues should be reinvested into local artists, venues and events, like in Berlin.

“Evaluate the impact of tourism revenues and reinvest a part in the creative content and the local scene in order to maintain and develop the cultural attractiveness of the metropolis. Berlin has done that. There’s a tax that Tourisme Montréal takes on each hotel unit, but there’s a small amount of this tax that we could give to artists, to those who create local culture and alternative culture,” he said.

By failing to include underground art in their funding, Carrère says the city is failing a key part of Montreal culture.

“I genuinely think it’s good to have the Jazz Festival and Quartier des Spectacles. But we need to have the choice of going mainstream in these spaces, to these big shows… All this money [is] put there and not a cent put on the underground scene, which is maybe the future of this mainstream culture,” said Carrère.

‘Cohabitation is key,’ says Projet Montréal

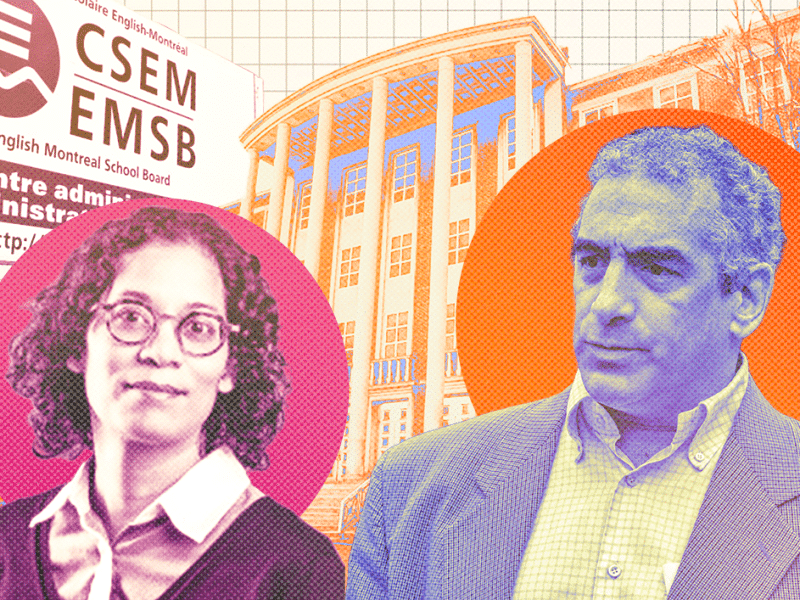

City councillor for Rosemont–La Petite-Patrie Ericka Alneus said she’s open to hearing what people have to say. She emphasized that nothing proposed in the project is set in stone.

“We’ve heard talk of the Latin Quarter [for a 24-hour zone], we’ve heard about rue Saint-Laurent… We’re not decided on the locations that could have that [24-hour permit], or the establishments that could have it. We’re not at the point to confirm anything. There’s still an openness that it’s not necessarily a fixed zone, but maybe it would be based on specific venues.”

She said the city will be working on revamping noise regulations to improve “cohabitation.”

“It might not be an issue that seems directly linked with artists, but if we offer the artist the opportunity to make the noise they need while assuring the comfort of others, we’re working on that cohabitation. Because one thing we’re realizing is that the noise regulations are the same all over the island, but there aren’t the same activities taking place all over the island,” she said.

Austin Wrinch stands in front of 3965 St. Laurent, where his venue the Diving Bell Social Club used to be. PHOTO: Emelia Fournier

“It’s about, how do we get everybody to get along knowing that some people are chilling at night and others are chilling during the day, but we’re all citizens of the same city?”

Alneus said that she has been hearing about people’s struggles with increased costs of living in the city through the public consultations that have taken place, and said these voices would be taken into consideration when the final policy is released on April 10, 2024.

The Diving Bell closure: a case study

Sitting in a café across from 3965 St. Laurent, where the Diving Bell Social Club used to be until December 31, Austin Wrinch told me his venue’s location was never ideal. It was on the third floor, with low ceilings, above three other bars. But, it was a venue home to small shows, karaoke nights and more. A new landlord combined with frequent noise complaints from people who moved in next door during lockdown made their exit a lot hastier.

“This guy’s trying to sell the building, the roof is leaking, all the windows need to be replaced, the pipes leak. We’re going to sign this guy’s [five-year] lease, then either we leave on Dec. 31, 2023, or it’s Dec. 31, 2029. So we made the decision then that, hey, the Diving Bell is working culturally. It’s never been better, but we’re not going to win here.”

They’ve also been subjected to Montreal’s “Wild West” noise complaint system. During lockdown, people moved into the now-tranquil apartments right next to 3965 St. Laurent, home to Barbossa, Champs, Blue Dog, and, at the time, the Diving Bell. Those liquor permits have been in effect since the 1970s, said Wrinch, but after the new tenants moved in during lockdown, he started getting noise complaints when the Diving Bell was allowed to reopen. While they never got fined, it was always up to the discretion of the police officers who showed up.

“It’s like moving in above Schwartz’s and then [saying] ‘I didn’t know it would smell like smoked meat here.’ Dude, you moved into the place that people want to live [in] because it’s in the centre of town,” said Austin.

He went into the landlord’s apartment next to the Diving Bell to check the noise level during a soundcheck when she texted him that they were playing too loud.

“It was this riot girl punk band playing Blink-182 covers during the sound check. So that’s literally the worst noise it could ever be. Obviously I’m biased, but she had to shush me as we were talking [to hear the sound check]. I was like, literally the sound of Saint Laurent street traffic is drowning that sound out.”

“I also saw that the wall that we share on our side where we put in a huge, thick $6,000 soundproofing, no soundproofing this side. It’s all the nice exposed brick, which is obviously to [show] ‘Oh, what a nice, cool apartment.’ The fact that she could have bought that building 30 years after these bars have been operating and then be like, ‘I don’t have to do any soundproofing.’ And she can just call the cops for whatever reason,” said Wrinch.

“Obviously, housing is an issue. But to me, it’s not even about housing as much as it’s about just allowing for residential landlords to have all the power.”

Wrinch says that implementing the agent of change principle and having clearly defined acceptable decibel levels would help prevent those issues. He and his fellow venue partners are on the hunt for a more accessible venue, but no matter what they find, the power imbalance between landlord and tenant will still be at play.

“Mark my words, in a couple of years, [3965 Saint Laurent] is going to be empty. They’re just waiting for it to rot so they can rip it down and turn it into some sort of condo with a juice place in the bottom or whatever. That whole building has and continues to kind of just be an example of holding on for as long as you can, for the sake of just trying to make space useful for the community versus literally this building here that’s been sitting empty for longer than the Diving Bell was ever there.”

Wrinch said Projet Montréal needs to listen to the people who are creating nightlife in the city.

“Culture and good [music] scenes aren’t just inevitable. In fact, they’re the opposite of inevitable. They’re unlikely to occur unless you’re putting protections on and actually deciding to protect the things that we want.” said Wrinch.

Projet Montréal will be announcing the adoption of recommendations on its nightlife policy on April 10, 2024 in a virtual public assembly. If you would like to voice your opinion on Montreal’s nightlife, you can submit a written opinion to la Commission sur le développement économique et urbain et l’habitation to commissions@montreal.ca or contact your borough’s representative.

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.