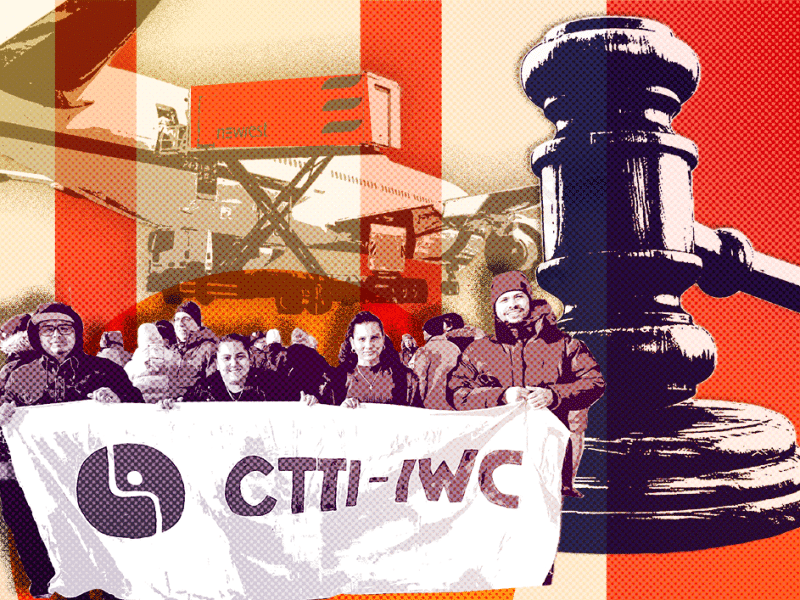

McGill Spent Over $1 Million Fighting Unionization

Union organizers at the university say this is part of a broader trend towards corporatization of the public institution.

McGill University spent $1.1 million fighting its employees’ attempts to unionize over the past five years.

Although the university has its own legal counsel and is in the midst of a $45-million budget cut for fiscal year 2025-2026, it pays a premium to outside lawyers who specialize in fighting unions. That’s according to documents obtained by The Rover and six sources inside McGill.

The sources say that, through its lawyers at Borden Ladner Gervais (BLG), the university has obstructed union business, contested certification at every level, and used stall tactics during negotiations. This period, which they say began four years ago, coincided with an explosion in outside legal expenses.

In 2022, McGill’s law professors voted to unionize. The university spent $96,200 on outside legal fees, more than tripling the previous year’s budget. After the law professors organized, professors in the faculty of education and arts followed suit. By 2024, when the arts profs voted to unionize, McGill was paying nearly half a million dollars in legal fees each year, according to internal documents leaked to The Rover.

“I knew they were spending a lot on outside lawyers, but over $400,000 a year? I was shocked when I saw that number,” said Rine Vieth, mobilization officer for the Association of Graduate Students Employed at McGill (AEGSM) between 2019 and 2021. “When we organized in 2019, we encountered resistance at every turn. Every step of the way, they fought us. But I still never would have imagined they’re spending that much.

“It’s a super irresponsible use of public funds. McGill has in-house counsel. The negotiations are being led by McGill administrators. You don’t need a whole team of fancy lawyers there. This is a publicly-funded university, using public money to fight its own employees.”

Support your local indie journalists

While Quebec saw a wave of unionization in its universities during the 1970s, McGill’s first professors’ union did not form until 2022, when the faculty of law formed the Association of McGill Professors of Law (AMPL). In response, McGill hired BLG, a firm that employs over 800 attorneys in offices across Canada.

One of BLG’s lead lawyers, Corrado De Stefano, represented Walmart Canada when it was accused of union-busting in 2005. That year, Walmart laid off roughly 190 workers from its Jonquière store after they had voted to unionize. Laying off workers for unionizing is a violation of Quebec’s Labour Code.

Even so, De Stafano fought for the American retailer all the way to the Supreme Court, which ruled in favour of the employees, calling their dismissal illegal.

Working for McGill, De Stefano and his colleagues were found, by Quebec’s labour tribunal, to have interfered with unionization efforts by McGill’s law professors in 2024. The tribunal ruled that two emails, sent by McGill to its law professors on the eve of a strike vote, were an attempt to undermine the union’s credibility.

The first email contained an explanation of why McGill withdrew from negotiations with law professors and the second accused the union of spreading disinformation. In its ruling, the tribunal found McGill to be in violation of Quebec’s Labour Code and ordered the university to “cease all forms of obstruction and to refrain from interfering with union affairs.”

One union organizer says it felt like McGill was using their negotiations to send a message to other workers: that any attempt to organize would be fought tooth and nail by the university.

“(McGill) dragged their feet every step of the way,” said Kiersten Anker, vice president of AMPL. “They contested our certification right away. That should’ve been a sign. They lost that. They appealed it.

“We had to negotiate with them, sit across from them in a room and try to hammer out an agreement knowing they were contesting our very existence.”

AMPL went on strike in 2024 after negotiations with the university broke down. Anker says that, leading up to the strike vote, McGill cancelled three negotiation sessions at the last minute.

“By the time the strike vote came around, even our most ‘kumbaya’ members were saying ‘Yeah, I think we need to go on strike,’” Anker said. “Management’s approach to negotiating definitely pushed whoever was sitting on the fence to fight back.”

Though AMPL’s decision to strike nearly cost students their semester, both parties managed to resolve the dispute with a compromise.

One of McGill’s chief concerns was that if law, education and arts professors each had their own bargaining units, it would make for an endless and inefficient negotiation process. To that end, AMPL agreed to take a federated approach to unionizing, where some aspects of their contract would be negotiated by a bargaining unit that also represents arts and education professors.

Other, more faculty-specific working conditions, like salary and course load, would be negotiated by individual unions.

The Quebec government’s decision, in 2024, to increase tuition for largely anglophone international students and for Canadians from outside Quebec has hit McGill particularly hard. This increased pressure on the university to outsource its services to cheaper non-unionized workers and rely on private donations.

Two years ago, the university laid off 65 floor fellows — a group of older student workers whose job was to live in dorms and help first-years adjust to university life. The floor fellows, who were unionized, worked with students who may have suicidal ideation, they received complaints of sexual violence, and were trained in overdose prevention.

After being given just a few hours notice, they were summoned to an eight-minute Zoom meeting and told their jobs were being eliminated. The floor fellows were replaced with a “residence life advisor” who, rather than living among the students throughout the semester, sat at a desk in the lobby during normal office hours, and “residence life facilitators,” whose role is mainly to plan events for the students.

“They gave a lot of reasons for the layoffs, but ultimately I think it came down to money and the fact that these were unionized workers,” said Casey Broughton, a union organizer at McGill during the 2024 law faculty strike. “Ultimately, students lost an essential service over this. It’s just one example, but the university is privatizing much faster than people realize.”

Anker said that, as the university increasingly corporatized over the past two decades, conditions among the faculty deteriorated, leading them down the path of unionization.

“The wisdom, when I joined 21 years ago, was that unionizing wouldn’t make sense at McGill,” Anker said. “Professors would go on to be deans and then cycle back into their role as professors. That was the same with a lot of executive positions at the university where it’s basically a faculty-governed institution. So why would we unionize against ourselves?

“But things have changed. There has been a gradual corporatization of the university, a centralization of power. That kind of cycling in and out of professors to deans to professors that kept the admin in touch petered out. People tend to move up the ladder and then move on. They become judges, go on to another university, bigger and better things.”

One of the most glaring changes, Anker said, was the pay gap between professors and management.

Over the past 10 years, funding dedicated to executive and management salaries at McGill increased by 118 per cent, according to a report by the Association of McGill Professors of Science. During that same period, academic payroll grew by just 6 per cent. Median pay among academic staff, meanwhile, has declined since 2016, according to a report by the McGill Association of University Teachers.

“This is the university going from a public service to being run like a private business,” said Broughton, a graduate student in law. “It doesn’t bode well for anyone who isn’t upper management.”

McGill did not provide a comment when contacted by The Rover.

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.