Mohawk Researchers Find Contamination in Kahnawake’s Air, Soil and Water

Armed with borrowed gear and a do-it-yourself attitude, Mohawks are uncovering a cocktail of contaminants near their homes and playgrounds.

Kerry Diabo is convinced that the land he lives on and the air his children breathe are slowly poisoning them.

“We’ve been plagued with rashes, nose bleeds, headaches. The kids, too. It’s scary to think we can’t protect them,” said Diabo, who lives in Kahnawá:ke, Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) territory.

“And sometimes when we test the air quality, it says we all need to be inside. It’s a summer day and our kids should be able to play on our land, in our territory, without having to breathe in chemicals. Instead they have to take shelter and wait until it’s safe.”

When we met with Diabo and his wife Katsisahawi on a sweltering day in August, they sat on lawn chairs and watched their two youngest roughhouse in the tall grass. Every couple of minutes, a dump truck rumbled by, kicking up a cloud of dust on its way to the JFK Quarry just a few hundred meters away.

In the forest that sits between his land and the quarry, Diabo has quietly been collecting soil, water and air quality samples. The results of one surface water sample — tested by a laboratory across the river in Montreal — showed levels of the metal manganese to be 10 times higher than what Health Canada considers safe.

Another water sample, collected by a dirt road that snakes around the quarry, found concentrations of fluoride 28 times higher than the maximum acceptable level. Though both elements are naturally occurring, their presence can be exacerbated by mining, blasting and other industrial activities.

Continued exposure to high levels of these elements can cause tremors, muscle spasms and cognitive deficits among a litany of health problems. And that’s not taking into account what the air might be doing to Diabo, Katsisahawi, their four children and the baby she’s due to deliver next month.

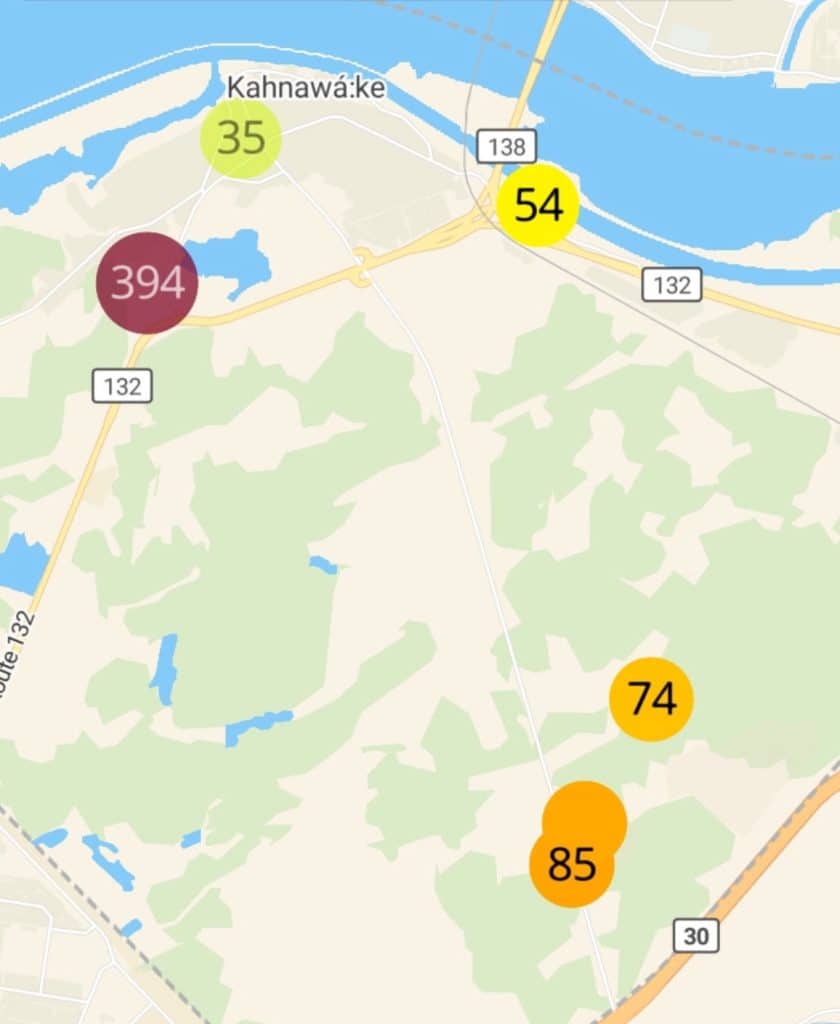

An air quality index (AQI) sample, taken near Diabo’s house on Monday, found levels of carbon dioxide and particle pollution well beyond what’s considered safe. The AQI uses this data and produces a score between 0 and 500. Anything below 100 is within environmental norms. The reading outside Diabo’s home was 394.

That number is over eight times higher than two other AQI samples collected at the exact same time at nearby sites on Mohawk territory. These are considered “emergency conditions,” according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, which invented the AQI scale.

Diabo says he is certain the cause of this contamination is the JFK Quarry and all the trucks passing by his home. But two experts working with him say there’s still not enough data to make that conclusion.

“The lab tests, and I’ve looked at them, they should worry anyone who lives on the territory,” said Daniel Green, an environmentalist and former deputy leader of the federal Green Party. “But they’re incomplete. What we need is comprehensive testing over longer periods of time. Without that, we only have one piece of the puzzle.

“It’s like if you ask me what the score in the hockey game is and I told you, ‘Montreal 5, Detroit…’ We’re missing information.”

Marcia MacDonald is a geneticist and researcher who offers her services to communities experiencing the effects of global warming or environmental degradation. While praising Diabo’s fieldwork and deferring to his knowledge of the land, she says more research is needed to isolate the source of contamination.

In Kahnawake, on Montreal’s South Shore, there’s such a well-documented history of outsiders poisoning Mohawk land by dumping fuel and industrial waste that it can be challenging to figure out where pollution comes from, according to Green.

When the St. Lawrence Seaway was built, during the 1950s, construction crews dug up acres of Mohawk shoreline and dumped thousands of tonnes of refuse on the south side of the reserve. Mohawk land was also expropriated to build the Canadian Pacific railroad, the Mercier Bridge, Highway 30, Route 132 and the transmission lines that export electricity from Quebec to New York State. Each of these massive projects contributed to the degradation of Kahnawake’s land and the welfare of its 8,000 residents.

Now, the JFK Quarry is moving forward with a plan to 100-acre crater with 8 million cubic meters of contaminated A-B soil. The quarry’s owner, Frankie McComber Jr., says the term “contaminated” is misleading.

“Most of the soil in and around Montreal, if you were to test it, would fit the criteria of contaminated A-B soil,” said McComber, in a telephone interview with The Rover. “Anything that isn’t exactly as it would be found in nature is considered contaminated. A cigarette butt, a beer bottle poured out on it, these are all technically contaminants.

“I have kids in this community, I wouldn’t do anything to harm them. What I tell everyone who criticizes us is this: ‘Come visit the quarry. We’ll show you everything we do. We have nothing to hide.’”

In Quebec, soil is considered “A-B contaminated” if it has between 1,000 milligrams of manganese per kilo and 2,200 mg/kg. The average manganese concentration in Canadian soil is 80 mg/kg, according to Environment Canada.

While the mineral is naturally occurring, the combustion of gasoline and the disposal of industrial waste can dramatically increase its presence in soil, surface water and — if left unchecked — all the way into the community’s groundwater. Still, AB is the lowest level and most common type of contaminated soil in Quebec.

Accepting 8 million cubic meters of it would mean taking in roughly 350,000 truckloads of contaminated soil onto Mohawk territory over a 30-year period. McComber said he doesn’t anticipate an increase in the volume of trucks that pass through his quarry.

“The people dumping soil will be the same people who buy our crushed stones,” McComber said. “We’re going to make it efficient. … I don’t want my legacy, on our land, to be a giant hole. I want us to fill that hole and, yes, this is a very long time, but maybe one day we can build over it.”

When contacted by The Rover, the Kahnawake Environmental Protection Agency (KEPO) waited eight days before providing the following response:

“It was determined that the MCK (Mohawk Council of Kahnawake) will not speak on the issue until there are further developments. We have your request and will keep it open until those developments occur in the next few weeks.”

That was three weeks ago.

Support boots-on-the-ground journalism.

Unsatisfied with KEPO’s handling of the quarry issue, Diabo has started taking drone footage of the site and sometimes sneaks onto it through the woods to gather his samples. With minimal resources and learning what they can from professors, university textbooks and the internet, Diabo and Katsisahawi are slowly building their case.

“I don’t think either of us anticipated we’d be doing this much learning and sneaking around but it needs to be done,” said Katsisahawi. “This is for our kids and their kids and generations after that.”

This summer, they attached a water bottle to the drone so that Diabo could lower it to the bottom of the quarry and collect water to have it tested in a lab.

“I warned him not to jerryrig a $2,000 drone, those things aren’t built for collecting samples,” said Green. “But I also understand that he’s desperate for answers.”

During Diabo’s first attempt at collecting a sample from the air, the drone crashed.

KEPO has led projects to restore land destroyed by the construction of the Saint-Lawrence Seaway and revitalize a system of creeks that’s under threat on the territory. They’re also working to mitigate any damage that might come with the JFK landfill project and a proposal to reopen an asphalt plant in the quarry.

Their silence on the matter feeds into Diabo’s criticism of the band council. As a traditionalist, Diabo is one of thousands of Mohawks who refuse to vote in band council elections, which he considers an extension of the federal government. He derisively refers to MCK Grand Chief Cody Diabo as “the mayor of Kahnawake” and belongs to a longhouse — where issues of Mohawk spirituality, sovereignty, land management and governance are often intertwined.

One of Diabo’s research collaborators, Stewart Myiow, is so opposed to any acknowledgement of an outside government that he refuses to pay his hydro bill, opting instead to live without electricity.

“I’m not going to pay for stolen electricity taken from stolen rivers,” said Myiow, during an interview outside Diabo’s home last month. “We are a self-governing people and there’s no band council that can tell us otherwise.”

One expert who has studied land use in Kahnawake says the territory’s proximity to Montreal, its rock quarries and access to the river make it incredibly valuable. And that value, he argues, is often exploited by outsiders.

“Quarrying in Kahnawake goes back at least 200 years, but the decisions about who gets to mine rocks and how it’s done have often come from the outside,” said Daniel Rück, an associate professor of history at the University of Ottawa. “Because of the way colonialism operates, the decision-making about how quarrying gets done, who owns the quarry and what rates would be charged was handled by Indian Affairs until the early 20th century.

“So you’d hear stories about people being concerned about dust, quarrying equipment being left on public land, piles of rubble being left all over the place. … The larger issue we’re getting at, is basically ‘What’s up with reserves? Why is there so much more dangerous and disruptive industrial activity on reserves than in neighbouring communities?

“It goes back to the Indian Act effectively giving Ottawa more power over what goes on in a community than the communities themselves. Because the community sits on extremely valuable land, and it’s a huge part of the economy. But when you look at all the pollution in Kahnwake, from the seaway to the highways to the railroad, it’s pretty clear Ottawa did a bad job protecting it.”

Over at the quarry, McComber has worked with an engineering firm to identify the risks that might come with backfilling the quarry with A-B soil. Among them, the presence of a peregrine falcon habitat that biologists will have to study and find ways to protect.

“I’m acting in good faith,” McComber said. The business owner has seen what’s happened with illegal dumping in Kanesatake, where outside trucking companies dumped thousands of tons of contaminated soil for over a year before the government intervened.

“We don’t want what happened in Kanesatake to happen here,” he said. “This is my land too, and I don’t want to see it go that way.”

For Diabo, the plan is an ecological disaster waiting to happen.

“I don’t have any other choice but to fight,” he said. “I’m going to keep going into the woods, collecting my samples, building our case. There’s four kids living in that house and another one on the way. If we can’t protect them, what the hell are we doing?”

Did you like this article? Share it with a friend!

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.