Montreal Election: The Year of Magical Thinking

Soraya Martinez Ferrada wants to use AI to help solve the city’s orange cone nightmare. Where have we heard this before?

In his only successful bid for mayor, Denis Coderre pitched Montrealers on a tech utopia.

Back in the heady days of 2013, long before doomscrolling, we still thought of our phones as evidence of progress, and Coderre seized on that enthusiasm.

“You take your smartphone, take a picture of (the pothole), send it back to public works and then, within 24 hours, they can manage it,” Coderre said, in an interview with The Link. “If you can have that kind of a relationship, it means that it works and that people can have a closer link to that (government) institution.”

It is easy, with 12 years of hindsight, to look back and laugh at how absurd Coderre’s promise was. As if the solution to an overworked and underfunded department was to flood them with requests from every citizen with a smartphone.

Of course, Coderre never came through on the fix-it-within-24-hours pothole promise.

Instead, he was a one-term mayor plagued by improvised policy ideas, a police force he weaponized against his enemies and an infrastructure deficit that ate up what little remained of his political capital.

Twelve years later, the tradition of magical thinking lives on in Coderre’s party. Ensemble Montréal — they renamed the team after Coderre quit politics the first time — is going to make this city “a pioneer in innovation.”

An administration led by Martinez Ferrada would use artificial intelligence to “bring the city closer to its citizens and deliver services that meet their expectations.” AI could speed up permit applications and coordinate construction sites to minimize chaos. Sound familiar?

As with Coderre’s smart city, Martinez Ferrada’s team is oversimplifying a vastly complex problem by leaning on our relative ignorance of AI. That’s not my opinion. Three engineers inside the industry told me this after reviewing Ensemble’s platform. None wanted to go on the record for fear of creating a conflict between their firms and a party that could well form government after the Nov. 2 elections.

Support Independent Journalism.

“There’s so many variables on these job sites that we can’t account for,” said one engineer. “It’s an old city. When you tear up the road you get surprises. The weather doesn’t always cooperate and that can throw scheduling off. And you’re dealing with subcontractors and sub-subcontractors.

“It’s a lot of moving parts.”

The problem of poorly coordinated job sites was one of the key findings in Montreal’s 2024 Auditor General Report. The report found that 37 per cent of Montreal’s roads are in poor condition, which is exacerbated by the fact that our city lacks a formal system to coordinate construction sites.

But it also revealed that some boroughs weren’t spending their entire pothole budgets. In the Sud-Ouest, for instance, only $5,000 of its $100,000 annual pothole budget was used. Why? Because so much of the equipment needed to fix asphalt was damaged or broken. So they just stopped filling potholes.

There’s not much an algorithm can do to address that.

Last summer, dozens of blue-collar workers in the Sud-Ouest refused to collect garbage and do maintenance one morning in response to a toxic climate and poor conditions. The straw that broke the camel’s back? Management threatened to dock their pay if they didn’t attend an employee appreciation barbecue.

On June 5, the morning they walked off the job, the workers told me that four of the borough’s 10 garbage trucks were out of commission and that two of its three sidewalk sweepers didn’t work. The team tasked with repairing sidewalks was also cut for the summer. They did not, in other words, feel appreciated by their employer.

I checked back with one of the workers last week.

The source said the following:

- Equipment and trucks are breaking down, but the mechanics don’t have the parts to repair them.

- Since the city’s parts procurement was centralized, mechanics sometimes have to wait days for a part they would normally have in stock.

- That’s going to be an even worse problem come winter when the trucks really take a beating.

Montreal employs about 6,600 blue-collar workers and hundreds of mechanics. If there’s a bottleneck in procurement, that’s a fortune in lost productivity.

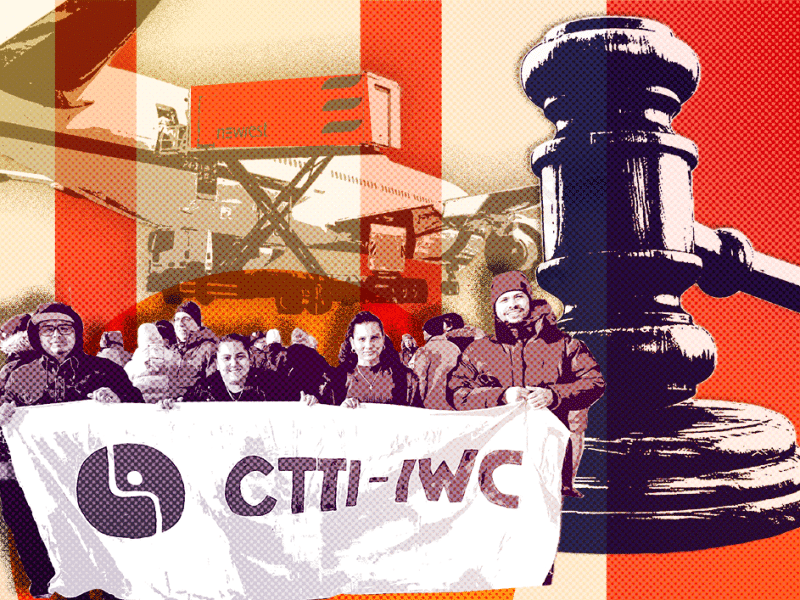

Another possible snag with the blue collars? Over 98 per cent of their union’s members voted in favour of a strike mandate three weeks ago. It’s just pressure tactics for now, but a strike isn’t out of the question.

These kinds of crises predate Ensemble Montréal and will long outlive the party. They are woven into Montreal’s political fabric.

Now, to be fair, the party isn’t relying on AI magic to fix everything. And the Sud-Ouest has been run by a Projet Montréal borough mayor since 2013, so you can’t exactly pin that on Ensemble.

Mirandez Ferrada says her administration would have a complete inventory of all current and future construction sites on the island within the first 100 days of its inauguration.

Poor management culture, overly centralized services and not enough boots on the ground are all addressed in Ensemble’s platform. Notably, Ensemble recognizes that after eight years of Projet Montréal in the mayor’s seat, “the number of managers and senior managers has increased by 18 per cent… while the number of blue collar workers has barely changed.”

The party’s solution is to freeze hiring for managers, to “streamline” the city’s organizational structure and ultimately reduce management staff by about 1,000 jobs. And, of course, to lean on AI to create new efficiencies.

But as with Quebec’s 2014 healthcare reforms, where Minister Gaétan Barrette got rid of around 1,300 managers throughout the system, cutting those jobs means losing expertise and offloading more work onto the workers.

Projet Montréal leader Luc Rabouin promises to heed the auditor general’s recommendation and centralize the coordination of construction sites under one boss. Recognizing the sheer amount of jobs that have been farmed out to subcontractors, Projet’s platform promises to give boroughs a bigger role in overseeing and executing major works.

Voters are understandably skeptical.

Rabouin is three points behind Martinez Ferrada in the polls, and with 41 per cent of voters undecided and an upstart party outflanking Projet’s left wing, the new leader faces an uphill battle.

Former Projet Montréal stalwart Craig Sauvé left Projet and later founded his own party, Transition Montréal, which borrows heavily from the platforms that helped elect Valérie Plante in 2017 and 2021.

How much borrowing? Well, just last week, Rabouin’s campaign manager quit Projet to join Sauvé’s party. And his solution for the construction nightmare — to create the Infra-MTL team tasked with patrolling the city’s busted infrastructure and fixing it in-house — has echoes of Plante’s 2017 platform.

Whoever takes the reins after the election will be faced with problems that no amount of cost-cutting and creative thinking can solve.

By the city’s own estimates, it will have to invest $10 billion over the next 20 years to keep our water infrastructure from collapsing. You cannot fix Montreal’s 3,600 kilometres of corroding pipes without closing roads, causing bottlenecks and upsetting merchants.

Our transit system, meanwhile, faces a $6 billion maintenance deficit that requires an injection of provincial spending at a time when our government is slashing essential services. Oh, and the transit workers are on strike this week.

Put mildly, we’re in for a rough few years. Or decades.

AI will not save us.

Did you like this article? Share it with a friend!

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.