Montreal Leans on Condo Developers to Fix the Housing Crisis

As the number of unhoused deaths rises every year, experts say corporate interest in the housing crisis excuses the city and province from serving the public.

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this article mentioned Leila Twenish without enough context, and we apologize for the misunderstanding.

Leila Twenish was a young Anishnabe woman and artist whose life was cut short before the release of her first album. She was deeply connected to music and to the revival of Anishnabemowin, and her work became the subject of a documentary focused on language, culture, and the power of Indigenous voices.

Leila was full of dreams. She wanted to create, to sing, and to contribute something lasting to her community. She made her Nation proud while trying to be herself in the city she loved, Montreal.

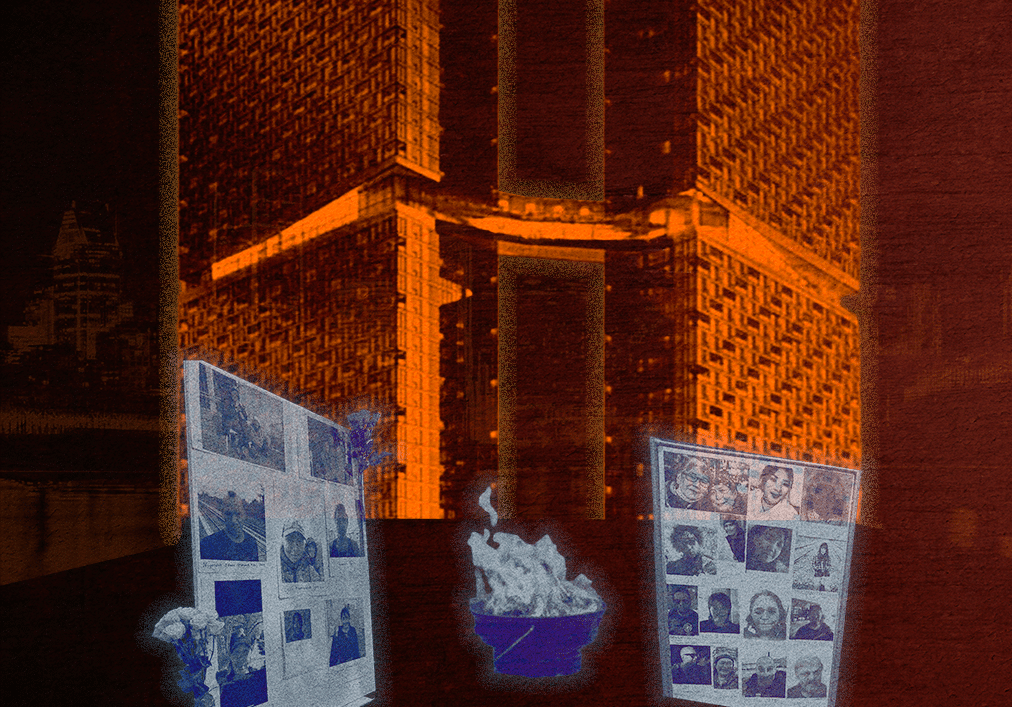

Cabot Square was packed on a cold, snowy day on Nov. 28, 2025, as over 100 people came out to honour and speak at a public memorial for the unhoused people in Montreal who passed in 2025.

Family, friends, and community members shared stories, as well as anger at a system that failed their loved ones.

Thirty-two unhoused people died in Montreal last year, and 24 of them were Indigenous. Similar memorials happen every year. Last year, in June, community organizers held a public memorial for 37 people who passed away over three years.

David Chapman, executive director of Resilience Montreal and one of the organizers of the memorial, says that the city is experiencing an ever-growing death rate on the streets, and Indigenous people are over-represented among those deaths. Yet these are unofficial numbers, because neither Quebec nor the City of Montreal has a system to track unhoused deaths in the same way Toronto, Calgary, or Vancouver does.

“What’s concerning about that is it’s a very convenient figure not to know. See, if you don’t know how many unhoused deaths there are each year, you don’t know that the numbers are rising, then there’s no pressure on you to create an adequate response,” says Chapman.

Montreal’s new mayor, Soraya Martinez Ferrada, built her platform on the promise to end homelessness. In 2026 alone, Ferrada promised $29.9 million for community organizations working with Montreal’s unhoused population, tripling the previous budget under Valérie Plante — who had doubled the Coderre administration’s homelessness budget. Most recently, the city added a new emergency shelter at the downtown YMCA with a capacity of 135, and is planning to add 500 more warming shelter spots across the city. The Hôtel-Dieu hospital site will also host another 50 people as a warming centre.

Support your local indie journalists

Aside from temporary measures the city is implementing, community organizers like Chapman continuously push for sustainable, long-term housing for those facing homelessness.

Last November, three major real estate developers proposed a project to build 2,500 social housing units for the unhoused. The $300-million project would be built on municipal land and would cost the city between $12 and 15 million annually in mortgage payments. After being built, the developers say they will hand over the housing units to the province’s Société d’habitation du Québec (SHQ) to own and operate them.

One of the developers, Groupe Mach, said it would cost the three developers $400 per square foot to build each 1,200 square feet of social housing — something they said they would do “pro bono.”

In a social media post about the project, Martinez said that “building collaboration between the City, the community, and private actors is the recipe for big projects that make a real difference for the people of Montreal.”

Lyn Lee, housing advocate and community organizer at the Comité d’action des Citoyennes et Citoyens de Verdun, is skeptical of the project. Lee spends her days fighting for tenants’ rights, helping people facing evictions and precarious housing situations.

On one hand, she is glad when a new social housing project adds more spaces for people in need. She understands the relief and optimism the community could feel when something like the 2,500-unit megaproject is proposed — people want someone to step up to make a sizable impact on the housing crisis. On the other hand, she’s not convinced that someone should be a corporation.

“At the end of the day, it’s kind of insulting — I spend my day trying to put band aids on gaping wounds that these exact predators, developers, have created, and the way that they make their profit is through this crisis,” says Lee.

Cogir Immobilier, Groupe Mach, and Groupe Devimco are major developers in Quebec, managing hundreds of buildings across the province. Devimco, known for its luxury condos that rent for roughly $2,000 a month for a one-bedroom apartment, has previously opted out of building social housing by paying the city a fee.

In 2021, Cogir threatened to evict at least 50 families living in affordable housing in Côte-des-Neiges. Many were low-income tenants and said at the time that the developer was wrongly accusing them of missing rent or other minor payments.

While real estate developers continue to act in pursuit of profit, they are also increasingly involved in public issues like homelessness and social housing.

Last year, another major Quebec developer, Devcore, built a container home village at the largest encampment in Gatineau. The same developer also set up a temporary shelter for asylum seekers in a hotel and conference centre in Cornwall. Lee says these issues are the responsibility of our governments, and letting developers manage them sets a dangerous precedent.

“I do think it’s just really about normalizing the private sector — normalizing that (the city) can subcontract things to the private sector to replace public services that the government is supposed to be doing, like building social housing,” says Lee.

Another instance occurred in 2021 when a developer in Montreal, District Atwater, took the city to court after it tried to purchase a plot of land in Verdun for social housing. As District Atwater had plans to use that land, the developer challenged the city’s exercise of its right of first refusal. After a two-year legal battle, the city made an out-of-court deal, which ended in the developer keeping the land and promising to build 200 social housing units.

Lee says that, to her, the whole situation showed that developers are above the law; they can keep the municipal government in court for years and make them fold to their demands. Lee and other community organizers in Verdun hoped the entire plot of land would be used for social housing as intended, rather than just a fraction of it.

“People are desperate — I am, too,” says Lee. “On a personal level, I do understand, a lot of the time when I hear any kind of social housing being built, I’m like, ‘Okay, well, it’s something.’ I have people coming here every day who are on the brink of collapsing, not being able to pay rent, on the verge of eviction. So in my mind that’s one more unit to put someone like that in… but it’s not the solution at all.”

Sarto Blouin is a Montreal developer who worked on the project at the former site of the old Montreal Children’s Hospital. He says that the city makes it tremendously difficult to build social housing, even for developers like him who were keen to do so. The project was meant to have 174 units of social and affordable housing that were ultimately never built because the city couldn’t come to an agreement with the real estate developer on the cost and design of those units. The developer finally opted to pay $6.2 million for not building the units rather than continuing to negotiate with the city.

“Social housing programs are entangled in too many standards and implementation conditions (too many people, too slow, too dependent on funding from various sources, too many levels of government involved, too many high construction standards like Novoclimat, etc.),” Blouin wrote, in an email to The Rover.

Blouin also cited that these barriers are why the bylaw for a Diverse Metropolis, known as the 20-20-20 bylaw requiring at least 20 percent social housing, 20 percent affordable housing, and 20 percent family housing in new constructions, never worked. The former Valérie Plante administration that enacted the bylaw wanted to have 60,000 new social housing units built in the city over 10 years, which has not come to fruition. According to the city’s website, the bylaw led to the equivalent of 2,783 social, affordable and family housing units since 2021.

Social housing requirements from the city, according to Blouin, are disconnected from the realities on the ground and also demand higher standards and regulations than they do for high-end condos. He adds that he thinks the change in municipal government will be an improvement to the situation because they have been consulting with construction and housing groups to be able to work better with them.

Yet as these deals and projects are discussed and debated, the reality of people suffering the consequences gets worse each year. In 2024, there were 9,307 people experiencing homelessness during a count of the homeless population conducted across 16 regions in Quebec — about 42 percent of them were in Montreal.

Na’kuset, executive director of the Native Women’s Shelter of Montreal, says she wants the government to wake up. She was surprised and disappointed that nobody from the city showed up at the memorial to honour those who passed away. She asks: if they say ending homelessness is their top priority, then why aren’t they here?

“What happens in Montreal is that everyone points fingers,” Na’kuset said “So the city will say, ‘Well, it’s not really our job to help Indigenous people, it’s the province’s job. And the province says ‘No sorry, it’s federal,’ and federal points back to the city, and it just keeps going on and on and on, and no one actually helps. It freaks me out that the new municipal government says homelessness is our number one (issue)… then you freaking show up if it’s number one. Be here, see who passed away, you make sure it doesn’t happen again. I don’t want to come back in a year and have the same amount exactly.”

When Dr. Stéphanie Mari-Anka Marsan went up to speak at the memorial, she looked at the four boards of photos and read out the names. Through her work as an addiction medicine doctor, she got to know many of the people in those pictures.

She said she listened to their stories, laughed with them, and felt pain and sadness with them. But she said they were not defined by their hardships and that they were storytellers, knowledge keepers, parents, siblings, artists, patients, helpers, and dreamers.

“Each carried a history, each carried a voice, and each one of them carried a future that was left unprotected, that should have been protected. Their passing is not inevitable,” said Marsan. “They’re the result of choices our society makes about housing, about access to care, about whose suffering is noticed and whose suffering is ignored. So as we honour them, we must also hear the responsibility their absence places on us.”

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.