Municipal Elections: “The City Stops for No One”

Despite a progressive mayor and council, Montreal’s crisis of extreme poverty was the dominant force during Projet Montréal’s time in office. Would electing Ensemble Montréal change anything?

Their bodies turned up in the dark corners of the city.

Amanda died in a motel room on St. Jacques St. They found Nico in a tent under the Ville-Marie Expressway, and, before that, paramedics pulled Elisapee out of an unfinished condo tower at Cabot Square. She had frozen to death after being kicked out of the Atwater metro in November 2021.

I don’t remember where Mohawk Mike was when the drugs killed him, but after he died last year, I stopped going to street funerals. No matter how many you go to, they never get easier.

When I began documenting the rise of extreme poverty for The Montreal Gazette, memorials for the homeless weren’t uncommon. After Marc Crainchuck’s friends found him lying dead under an overpass in 2017, workers at the shelter he frequented held a ceremony for him. Zach Ingles, a youth pastor who knew Marc, sang Amazing Grace as mourners sat and cried in the old Anglican Church on Atwater Ave.

Back then, you might see two or three funeral services over the course of a winter.

The crisis almost felt manageable. You knew who was sleeping outside and who had hustled themselves an apartment for the cold months. When someone stopped showing up to the old church, you knew if it was good news — they got off the street — or bad — they were locked up. You got to know people back then, to go to AA meetings with them or help them bandage a wound in the food court of a mall as shoppers sat and stared.

It’s been eight years since I started reporting on the streets around Cabot Square. In that time, Montreal’s homeless population grew from about 3,000 to 5,000 — that we know of, because the true number is almost certainly higher. That coincided with a doubling in the price of rent and real estate on the island. And as the system began to buckle under the weight of so much misery, the streets got deadlier than ever.

In 2017, some 181 people across Quebec died of drug poisoning, according to public records. Last year, the fentanyl crisis killed 645 people throughout the province. That’s almost twice the number of people who died in a car crash that same year. The vast majority of those drug deaths happened right here in Montreal.

It’s impossible to think about the eight years under Projet Montréal without addressing the elephant in the room: far more people are living on the streets today than were when the party began its mandate. Would things have been any different under a Denis Coderre administration? Almost certainly not.

But when it comes to politics, we can’t live in hypotheticals.

***

The crisis of extreme poverty is being felt in cities across Canada, with Toronto seeing its homeless population more than double since 2022 and Metro Vancouver’s reaching over 5,000 for the first time in its history.

To be fair, funding for homelessness, shelters, and social housing lies almost entirely out of the city’s jurisdiction. Quebec’s health ministry funds anti-homelessness initiatives, Canada is the authority on housing, and the city more or less coordinates everything on the ground.

But even with Quebec investing a record $400 million in homelessness initiatives since 2021, the problem has gotten wildly out of control. Premier François Legault has sought to blame “100 per cent” of the crisis on immigration and a rise in refugee claimants. The latest study on Montreal’s homeless population suggests only about 10 per cent of those living on the streets are immigrants.

The explanation is actually far simpler.

“People don’t have any extra income to inject into the economy. All of their money is going to the landlords and the banks,” said Jason Prince, an urban planner and Concordia University professor who specializes in social housing. “In less than a decade, people went from spending $900 on a two-bedroom apartment to $2,000. So the cash that would’ve been flowing back into small businesses and the local economy is just being funnelled to the city’s richest people.

“And those at the bottom — the ones who were spending 80 per cent of their income on rent — many of them wound up on the street.”

In response to runaway real estate speculation and a rise in house flipping, Projet adopted bylaws to prevent renovictions — using the pretense of major renovations to evict a tenant and jack up the rent. They also promised to create a renters’ registry during the 2021 election. For years, tenants’ rights groups had been calling for a legally binding registry, one where landlords are forced to publish the amount they charge, as a way of stopping illegal increases.

But the city’s renoviction bylaw only applied to buildings with eight units or more, representing just one-third of the city’s rental units. Another problem: making the registry mandatory would require provincial legislation from a government that has consistently weakened tenants’ rights over the past seven years.

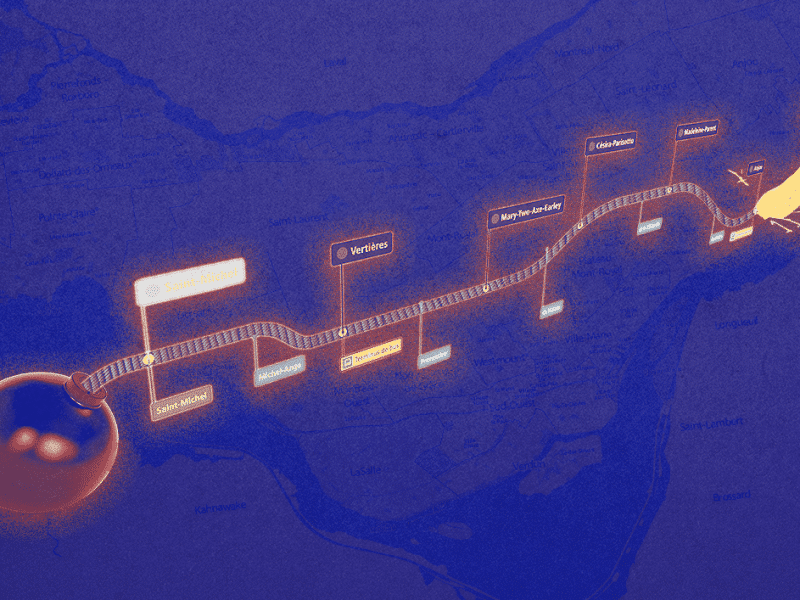

So rather than force landlords to fill out the registry, the city put the onus on renters to enter that information into an interactive map. And because Projet’s map doesn’t require proof of contract or lease, tenants contesting an illegal increase before Quebec’s renters tribunal can’t use the registry as evidence, effectively rendering it useless.

“I know people in Projet Montréal, I have members of the party on speed dial, and I wanted them to succeed so badly, but I’ve been disappointed,” said Ricardo Lamour, a writer, law student and activist. “We’re in a crisis; the city should be requisitioning city buildings and calling a state of emergency. What if the economy gets worse? What if people start losing their jobs because of the trade war, how many more people will wind up on the streets before we do something?”

Ahead of Sunday’s election, Lamour has been pushing a report called Profit Montréal, authored by an anonymous group of activists who outline what they believe is Projet’s failure to address the crisis of extreme poverty in Montreal.

In it, the authors point to the police’s ballooning $800 million annual budget, which was around $600 million when the party came to power in 2017. Projet inherited a police department under investigation for a culture of bullying, favouritism and impunity among its top brass. Even after police chief Philippe Pichet resigned in disgrace and the department consistently ran a deficit, its budget only grew as other departments in the city struggled to stay afloat.

The Profit Montréal report also looked at the construction of over 27,000 new condo units and — because of renovictions — the removal of over 1,000 rental units across the island.

Longtime Projet councillor Marianne Giguère says she’s seen the report and that she’s painfully aware of the crisis.

“We’re living in a crisis the likes of which most of us have never seen before,” said Giguère, who was first elected in the Plateau-Mont-Royal district 12 years ago. “All I can say is these are fundamental concerns, to be able to afford rent and groceries, that’s the basics of life.

“For years, we would compare ourselves and say, ‘At least Montreal isn’t Vancouver, at least Montreal isn’t Toronto,’ but we’re catching up. The divisions between the very rich and the poorest are growing. The minute someone sees that their apartment building is up for sale, they panic at the thought of having to go back into the market. People are fed up, people are scared, and I totally understand the reflex to look to (municipal) leaders and be disappointed.”

Giguère says she knows people are tired of hearing about the Quebec government having way too much say in how Montreal is funded.

“The way it works, in Quebec, is that we’re way too dependent on the minister of municipal affairs to get anything done,” said Giguère. “We’re on the frontlines, we’re the ones out there with folks who’ve been evicted and those living on the streets, but we have almost no levers to be able to deal with the problem.”

The complex nature of funding social housing is also a major problem, according to Giguère. When a property comes up for sale, the city can and has used its “powers of pre-emption” to buy it for off-market housing. But the process can be gruelling.

One landlord, who spoke to The Rover on condition of anonymity, said he was given a notice of pre-emption in 2013 when selling a rental property in the Sud-Ouest borough. At the time, the city offered $200,000, but he refused.

“Over the next four and a half years, I tried to negotiate with the city, but they had no mechanism to do that,” said the landlord. “So it went into litigation. I would’ve accepted $300,000 to $325,000, but it was like talking to a bureaucratic wall. Once the process was over, they paid $550,000 plus expenses.

“(Sud-Ouest) Mayor Benoit Dorais posed for a picture next to the property, announcing social housing with a golden shovel and a hard hat in 2014. To this day, there still isn’t a single social housing unit on the property.”

Compounding the crisis, Montreal’s two main sources of revenue — property taxes and issuing a “Welcome Tax” when people buy a home — seem only to encourage more development.

“The city is addicted to the Welcome Tax,” said Prince. “For each new luxury unit you build, there’s a Welcome Tax and property taxes in perpetuity. It creates an incentive for more expensive housing at a time when we’re desperate for affordable housing.

“And yes, the province sets the framework around how cities are funded. Changing that will require a fight with Quebec City. But previous administrations have shown some creativity. To pay for the Olympic Stadium, Mayor Drapeau introduced a new tax on cigarettes. We’re at a point where we need to think of a new mechanism for funding the city.”

To this point, Giguère said it feels like they’ve tried everything imaginable to get housing under control.

“We’ve met with our urban planners, studied the myriad ways we can try to slow down the runaway housing market, to stop people from evicting working folks, but it just feels like we’re plugging leaks on a sinking ship,” Giguère said. “The free market is a steamroller; it’s a giant machine that can feel unstoppable.

“I understand that people who work in the community, people who are overwhelmingly the victims of this crisis, are exhausted and disappointed. We arrived on the scene as the progressive party ready to attack the crisis, and from the inside, it’s been incredibly frustrating. We hear the criticisms, the criticisms are legitimate, but I have to say we feel powerless sometimes.”

In 12 years of municipal politics, Giguère has served on the Plateau’s borough council, the city council and the executive committee — the holy trinity of local politics. But these will be her last days in office, as Giguère will not seek re-election Sunday.

“It’s a great honour to serve your constituents and I will always feel lucky I did,” she said. “I tried my absolute best to do right by them.”

***

On the question of policing, Giguère says the rules are rigged against municipal governments.

At the height of the Defund the Police movement in 2020, Mayor Valérie Plante said she would be open to looking at ways of re-directing police resources towards crime prevention. But as with housing, Quebec ultimately sets the framework of how the department is funded and what benchmarks the city has to hit in order to respect public security requirements. Essentially, the city would have to convince the Coalition Avenir Quebec government to do a 180 on its tough-on-crime politics. Which feels unlikely.

If public polling around this election is accurate, it looks like these are the dying days of the Projet era. At least this iteration of it. Ensemble Montreal leader Soraya Martinez Ferrada has held a lead in every major poll since the campaign began and voters tell pollsters the city needs a new direction.

Some of what Ensemble is promising for the homeless sounds encouraging: spending $100 million to buy buildings and convert them to emergency shelters and another $120 million towards frontline workers. The city, under Martinez Ferrada, would create 2,000 transitional and permanent housing units with psychosocial support. But again, this would require massive buy-in from Quebec City and Ottawa at a time when both governments are preaching austerity.

More than likely, Ensemble will lean on its network of developer friends to soften zoning laws, densify housing and — according to market logic — stabilize the price of real estate by adding supply. But if that worked, Toronto would be one of the most affordable cities in Canada given how many condo towers have gone up over the past 30 years.

Finally, if it seemed like police had a free hand under Projet, Ensemble wants to increase the number of surveillance cameras across the city and centralize private security footage into a giant database accessible by the cops. Combined with recent news that the police department’s investigators will begin using artificial intelligence to review security footage, this is a recipe for turning the city into a mini surveillance state.

***

It cut deep when Elisapee Pootoogook died in 2021.

A few years earlier, I had helped get her to the airport on a cold winter morning, hoping she would make her flight off the streets and back to Inuit territory. She did, and for a time, things in her life were stable again. In the north, she could go back to sewing Inuit crafts and selling them to tourists. She hoped to find a safe place to live despite the region’s massive housing crisis.

But when she came back down to be treated for meningitis, Elisapee wound up back on the street. One night, when she was kicked out of the metro for loitering, the 61-year-old crawled into an unfinished condo building and sought shelter.

A worker found her body the following morning. Construction resumed the next day.

Even with a progressive mayor and party, this is a builders’ city. And the city stops for no one.

Great article. But I didn’t get your position on the elections. I am still going to vote 4 PM as the lesser of evil.