Police crack down on Chinatown homeless encampment

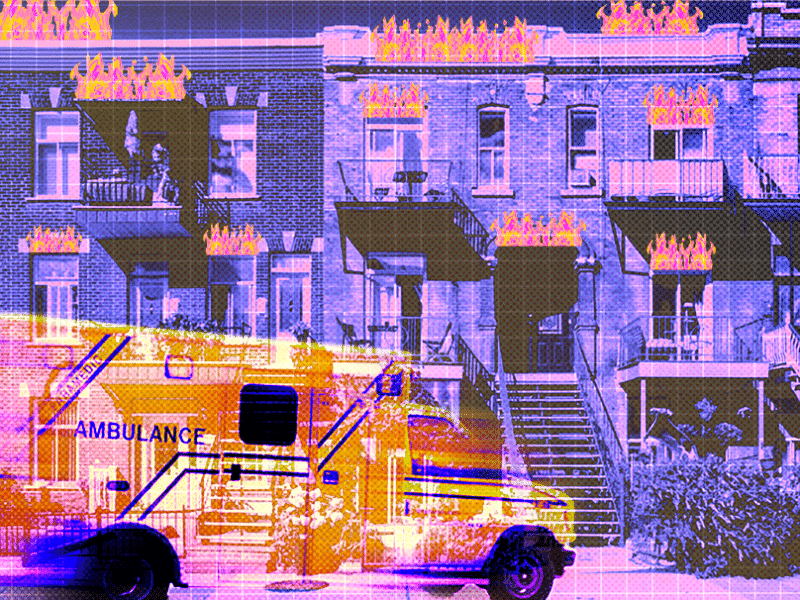

With homelessness on the rise and no long term solutions on the table, police are just displacing people from one desperate situation to another.

With homelessness on the rise and no long term solutions on the table, police are just displacing people from one desperate situation to another.

“Where the hell are we supposed to go now? To Berri Park, so we can be stabbed and beaten like dogs?”

Aside from that outburst, Michel Chabot took his eviction in stride. Chabot, 60, was one of at least 12 people police kicked out of a homeless encampment in Chinatown early Tuesday.

Most of those expelled from the camp were elderly and about half were Indigenous — including a pregnant woman who had to pile her belongings under a tarp to keep them from getting rained on. Two psychosocial workers from the city stood next to the police, occasionally offering words of encouragement.

“We’re putting them in touch with homeless shelters but there aren’t many spaces left,” one worker said. “It’s not a part of the job I particularly enjoy.”

This was the second time cops kicked Chabot out of an encampment in Chinatown. Six weeks ago, when he was staying in a tent near Viger St, officers waited for Chabot to leave camp for breakfast before swooping in.

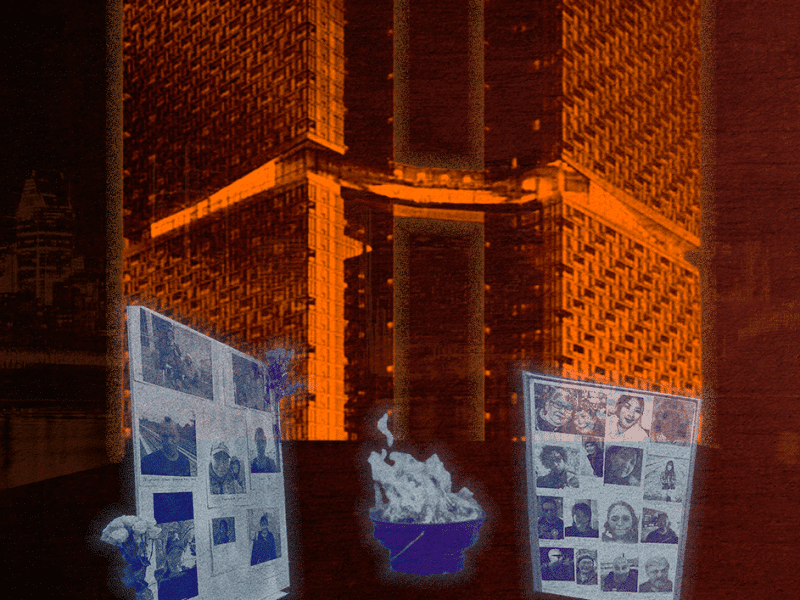

“They took everything I had in the world — including photos of my dead children — and left me with the clothes on my back,” said Chabot. “The only thing I had left was the clothes on my back and my dentures.”

Now, Chabot is being ousted from the vacant lot at 177 de la Gauchetière St. E., where he and a dozen others made a community out of five tents, and back onto the street.

“Some of us might have to find a garage or a backyard to sleep in for the next bit,” said a woman who wished to remain anonymous. “I don’t want to do that. But there’s no choice.”

Montreal’s homeless population has grown significantly since the beginning of the pandemic, when a lull in the economy pushed thousands of Montrealers into financial crisis. Sources at city hall say there are as many as 1,000 more people living outside than there were three years ago — when a census of the unhoused population found just over 3,000 people in Montreal sleep on the streets every night. Across the island, shelters are at or near capacity and many don’t feel safe sleeping in a crowded room with strangers. So they band together and form camps.

Last year, the provincial government introduced a five-year, $280 million plan to fight homelessness across Quebec. The city, meanwhile, doubled its annual spending on homeless initiatives to $6 million this year. Experts say it’s a good start, but it may not be enough to make a long-term impact on the crisis.

“It’s like if your sink is overflowing, should you invest in more pots and pans to catch the excess water, or should you address the root of the problem?” said Sam Watts, the CEO of Welcome Hall Mission. “Because right now, with homelessness, we’re investing in pots and pans. This won’t end until we realize that housing is a right and these people belong somewhere safe with a roof over their heads.

“It’s good to open up more emergency shelters, like we’ve seen in the past two years. But that’s just the symptom of something much larger.”

In the four blocks between Chabot’s encampment and the entrance of Chinatown on Saint-Laurent Blvd., you can see pockets of extreme poverty. People sleep on stoops outside a Buddhist temple, in laneways, by an abandoned school and under the trees that line de la Gauchetière.

Chabot keeps a clean tent and makes himself indispensable to whatever camp will take him in. He’s got a first aid kit and carries a pouch of the life-saving drug naloxone, which helps reanimate people who overdose on fentanyl.

Now that he has to leave Chinatown, he worries the only place left to go is one of Montreal’s most notorious haunts — the blocks surrounding Berri-UQAM métro.

“There’s hard drugs at Berri and they play rough there,” he said. “I can’t keep going on like this.”

***

Eviction at the encampment loomed all summer long.

Part of it came from a meeting between Chinatown business owners and the Montreal police in July, when concerns about cleanliness, sex work, and drug use in the neighbourhood were raised. The police report of the meeting didn’t include any mention of unhoused residents specifically, but it was presumed that they were the cause of all the neighbourhood’s problems.

The city responded by forming the Concertation Quartier Chinois, a multi-sectoral committee composed of community organizations, police and city officials. The committee is coordinated by the Faubourg Saint-Laurent, which aims to encourage communication between residents and the municipal government in the district.

The Chinatown Roundtable — created after widespread opposition to gentrification and neglect of historic buildings — represents the neighbourhood on the committee. Throughout the summer, it pushed for the city to respond to the issues being raised. But eviction wasn’t part of their requests.

“I was surprised by news of the eviction,” said Andy Hiep Vu, a coordinator of the Chinatown Roundtable. “Because I was reporting problems stated by citizens to the committee, and saying, ‘Hey, what’s the solution? What can we do to help people feel secure?’ And then they came with the eviction, so we were pretty surprised by it.”

Vu might also have been surprised because he received an email reply with the city’s eviction plan less than half an hour after he sent a follow up on the situation Friday.

But Marie-Ève Grenier wasn’t surprised with the news.

“I can’t say I was surprised because this year, Montreal has zero tolerance for encampments,” said Grenier, a social worker who sits on the committee. “Since March, we’ve received emails almost every week from people camping in discrete areas — where they don’t disturb anyone — and still they receive notices on tents saying they will be moved.”

Grenier is a community liaison for Spectre de Rue, an outreach organization that works to prevent the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases, HIV and hepatitis in Montreal’s Centre-Sud district. Their work has brought them to Chinatown, where Grenier meets regularly with drug users in an effort to promote safe injections and prevent overdoses. They said that since the spring, outreach workers have seen a concerted effort by city officials and law enforcement to look for camps and clear them out.

They recognized some of the new faces in Chinatown from nearby Place Émilie-Gamelin, which was cleared to make way for summer programming at the park. Displacing the homeless from Montreal’s downtown core isn’t as popular as comedy or jazz festivals, but street workers know it as an annual event paid for by those living with the most precarity. After all, evidence of overlapping housing and opioid crises hardly generates tourist dollars.

Grenier wasn’t present at the eviction on Tuesday. They said that given their work with some of the camp residents, they didn’t want to give any impression that they supported the operation in any way.

“We (at Spectre de Rue) are totally against evictions,” said Grenier, who uses they/them pronouns. “Every time we move someone and put their stuff in the garbage, they have to restart. And it’s often stuff that we give out as resources, like tents.”

“If your sink is overflowing, should you invest in more pots and pans to catch the excess water, or should you address the root of the problem? Because right now, with homelessness, we’re investing in pots and pans.”

—Sam Watts, Welcome Hall Mission

Both Spectre de Rue and the Chinatown Roundtable argue that eviction isn’t a solution for Chinatown. They say it merely shuffles unhoused residents to other pockets of the neighbourhood, and does not address its needs for long-term resources.

“We know that the pandemic pushed so many people out of their homes,” said May Chiu, a coordinator of the Chinatown Roundtable. “Nobody has been able or have the good will to tackle this issue, and so people are shoving it in each other’s courts.

“I think it’s a shame that people who are at the intersections of discrimination — vulnerable women, Indigenous and Black people, Chinese seniors — are all kind of thrown into a situation where they are pitted against each other, who end up pointing the finger at each other, rather than at the state, which has a legal obligation to make sure that its people are safe and housed.”

***

“Julie” came down from her apartment as police oversaw the eviction. Visibly angry about the situation, she says the camp has gotten out of control over the past few months.

“It used to be okay, the homeless who camped here used to keep to themselves,” she said. “But lately, there’s music until 2 a.m, prostitution, drugs being sold on site and it’s getting violent. The police are here every day.”

Julie — who did not give her real name — said she was assaulted last spring when a man broke into her apartment. When she told Chabot this story, he was empathetic but asked her how he knew her assailant lived at the camp.

“That’s what the police told me,” she replied. “They say they think it’s someone from this camp.”

Residents in Julie’s building sent a letter to city councillor Robert Beaudry on Sept. 2, outlining their grievances about the Chinatown camp. The city then added pressure to the vacant lot’s owner, fining him for not properly closing off the lot and ultimately forcing him to call 911.

Beaudry’s press attaché did not respond to The Rover’s interview request.

On Tuesday, as police oversaw the camp being dismantled, officers chastised the lot’s owner, imploring him to do a better job fencing his property in.

“We could be somewhere else, helping people,” one officer said. “Instead we’re here, doing this.”

There was little, if any, interactions between the unhoused residents and the cops. If anything, police appeared resigned to the fact that — once this camp is packed and gone — it’s just a matter of time before another one pops up and they get called in to clear it out.

“This is a sword strike in the water,” the officer said, gesturing at the eviction. “We’re just going in circles.”

***

On Tuesday, Chiu watched as people packed their lives into garbage bags and trickled out of the place they called home.

She stood in the rain and kept her eyes on police, making sure things didn’t escalate. The only time Chiu left the scene was to pick up water bottles for the unhoused pregnant woman and her friends.

Her voice broke as she spoke about the eviction.

“You can tell that they were a community,” Chiu said through tears. “They had just established themselves in what they thought was a safe space. It just broke my heart to see them all having to start over and scatter elsewhere, possibly into less safe situations.”

Chiu and Vu will convene a board meeting on Sept. 26 with other members of the Chinatown Roundtable, where homelessness is on a long list of pressing issues for the neighbourhood. They’re hopeful that it’ll be a step towards finding community-centered, long-term solutions for all of Chinatown’s constituents.

“We have to recognize the expertise of the people who live in Chinatown, which includes the housed and unhoused,” Grenier said. “They’re the experts, and they know what they need. It’s in respecting the fact that when people organize among themselves, they are better equipped to live with dignity and security.”

Chabot has no illusions that this is a dangerous life. A few weeks back, he had his head split open while trying to prevent someone from stealing a bicycle out of the vacant lot.

“I thought it was a fistfight but the fucker hit me with a metal bar,” Chabot said. “I know there are people out here who are dangerous but there are many more people just trying to survive. I’m 60 years old and just want to be left alone, what possible danger could I pose to this neighbourhood?”

Just then, Chabot turned to his tent.

“You can’t just pitch this thing any old place,” he said. “I’ve heard there’s a small camp under the (Ville-Marie Expressway). Not the one everyone knows about but another one, hidden from everything. I guess I’ll try living there.”

Oh, hi there…

Your support means the world to me and to my colleague Diane, whose intrepid reporting broke this story. These kinds of boots-on-the-ground stories used to be the cornerstone of daily news coverage in a city like Montreal. But with the industry collapsing, so many newsrooms barely have enough resources to chase daily headlines never mind invest weeks on an investigation. When you subscribe to The Rover, you’re supporting a return to the roots of muckraking journalism and helping people like Diane get paid to do what they were to. So please, if you can spare the cash, do us a solid and subscribe.

Your friend,

Chris