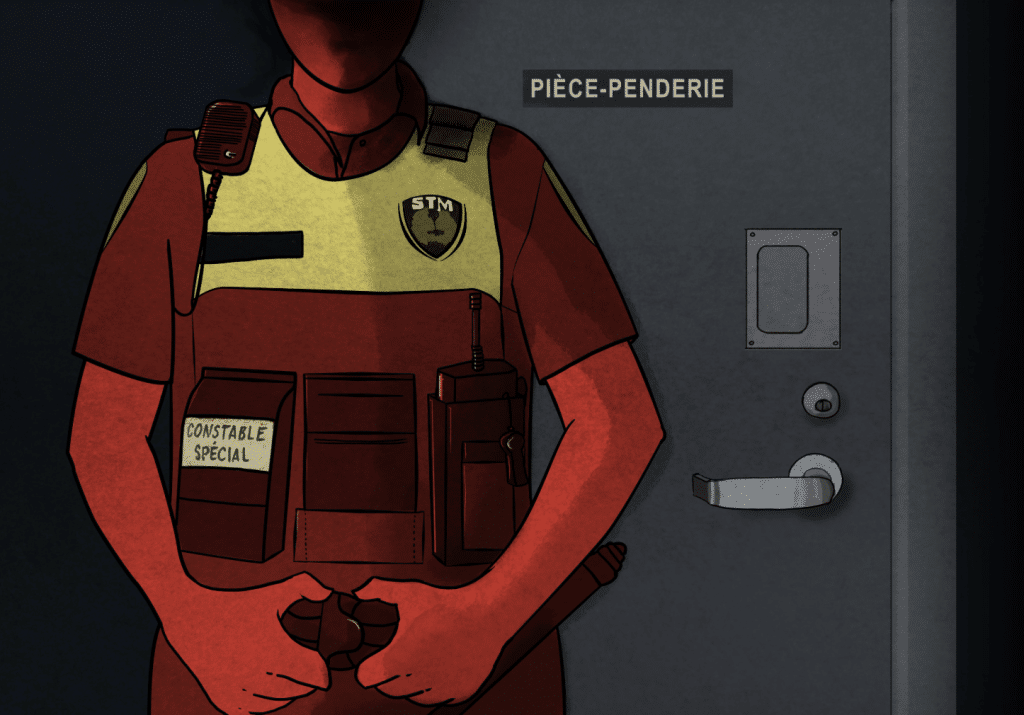

Police Ethics Commission Probes Sexual Assault Allegation Against Metro Constable

Witnesses say an Inuit woman was forced into a closet and groped by the constable for resisting a “move-along” order.

“He touched me. He grabbed (me). He hurt me.”

The following is based on eye-witness accounts of the events of the evening of March 16, 2025. These allegations have not been proven in court. Names have been changed to protect the victim, the witnesses and intervention workers from retribution. The accused will remain anonymous until an investigation into the allegations is completed.

On the evening of March 16, Mary*’s crying reverberated across the Atwater metro station from behind a locked janitorial closet.

“He’s putting his hands down my pants!” she screamed from behind the door.

Mary is a young Inuit woman, precariously housed, who frequents the Cabot Square area. A male STM special constable, X, was conducting a “search” behind closed doors after Mary resisted complying with the STM’s move-along order.

“He’s hurting me!” she yelled.

Ten minutes before she was ushered into the janitor’s closet, Mary and her friend Quin* approached community intervention workers Abe* and Brent* to ask for a metro ticket. These workers told her they didn’t have one, and Mary began to get upset and raise her voice.

This drew the attention of two STM special constables: a man and a woman. They ordered Mary and Quin to leave the metro. Days prior, the transit body had instructed constables to kick out individuals who were not using the metro to “effectuer un déplacement” — effectively instituting an anti-loitering law. The constables escorted Mary and Quin to an exit while Abe and Brent stayed back — but someone told them Mary was being arrested.

Abe and Brent ran to the exit and identified themselves as mediators, because they knew Mary well. X told them to “Stay back, don’t impede my investigation or I will arrest you.” Abe and Brent stepped out of the metro station to avoid an escalation. From outside, they saw the two constables open the janitor’s closet, usher Mary inside, and close the door. The female officer left Mary alone in the room with X. Then, the screaming started.

A few minutes later, the female constable returned, a Tim Horton’s coffee in hand. She let the intervention workers in the room, where Mary was sobbing, sitting on the floor in handcuffs, clothes in disarray, including her bra.

“He touched me. He grabbed (me). He hurt me,” she repeated between sobs. Mary said that X had put two fingers down her pants and rubbed her crotch. As Mary recounted this, X and his female colleague were writing up tickets for Mary and Quin. One of the tickets was not legible, the other one was written for “yelling in the metro.”

Intervention workers said that they lost contact with Mary for weeks after the incident.

The STM stated that the special constable accused of assault “n’est pas en fonction actuellement” (is not currently on duty). The transit authority did not specify how long he had been off-duty, nor did it provide a reason for this. An intervention worker said that he had last seen the constable patrolling metro stations back in June.

A lengthy investigation process

After hearing about this incident, Simone Page knew she had to take action to hold this STM special constable accountable.

“It was like (the constables were) trying to silence her by exerting their power over her, trying to show that they could do whatever they want, even in front of the mediators,” said Page.

Simone Page is a program coordinator at the Iskweu Project, an organization that addresses the crisis of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women, Girls, Trans, and 2-Spirit (MMIWG2S+) individuals in Quebec and supports Indigenous women in Montreal.

She says the STM’s special constables aren’t properly trained in de-escalation.

“It seemed like the search was a retaliation for resisting being physically pushed out of the metro,” Page said.

Her coworkers advised her not to contact the STM directly, but to submit a formal complaint to Quebec’s oversight body, the Bureau des enquêtes indépendentes (BEI).

Since 2021, STM constables can take specialized training at Quebec’s police academy to become “special constables.” These special constables are subject to the SPVM’s ethics code and, therefore, to the investigation process of the BEI. They do not carry firearms, but are equipped with batons and have the authority to make arrests.

Support your local indie journalists.

Page gathered the witness statement, images and other testimony — including images of a tearful Mary with marks on her chest taken just after the alleged assault. She submitted the complaint to the BEI on May 9, 2025. But only the victims themselves can directly trigger BEI investigations into sexual assault allegations — other complaints have to first go through the police ethics commission (Commissaire à la déontologie policière, or CDP).

On May 21, 2025, the CDP notified Page that it had opened a file regarding the complaint. Then, it was radio silence for months.

The Rover contacted the BEI on Sept. 29 to verify the status of this complaint. Communications officer Jérémie Comtois said the BEI had not received anything regarding the incident, but that the case would be under its purview to investigate.

On Oct. 1, a representative from the CDP contacted Page, saying that the CDP had been trying to contact the witness whose statement was part of the complaint — despite Page insisting that she would be the point of contact for the file moving forward.

The CDP said it would like to set up a “conciliation” meeting as part of its protocol before transferring the file over to the BEI, where the accused officer would sit down with the witness who authored the statement — not the victim — to give “his side of the story” and offer an apology.

Page said that would be inappropriate.

“It should not be us that’s asked to accept an apology, especially when it comes to discrimination or assault,” said Page.

As of writing, the BEI has not confirmed whether an investigation has been opened against special constable X, a process that takes on average five months. If the BEI determines the validity of these allegations, they are then pursued in court.

Comtois stated that only one other investigation into an STM constable had taken place, after which no charges were laid. This is despite reported abusive behaviour from STM special constables.

When asked what people should do if they witness an incident involving an STM constable, the constable’s union advised people to file a complaint via its online portal. The BEI said it is then up to the STM itself to file a complaint to the police ethics commission if a concerning incident is flagged.

Witnesses and third-party organizations that represent victims, like Iskweu, can still submit claims to the CDP directly. Victims themselves can submit a complaint directly to the BEI.

The STM stated that any disciplinary action would be determined after the ethics investigation has taken place and would not comment further on the investigation.

Meanwhile, Ensemble Montréal mayoral candidate Soraya Martinez Ferrada said she’d increase the number of STM special constables from 160 to 230 to address a “deterioration in the public’s sense of safety,” despite Montreal’s crime severity index declining to pre-pandemic levels.

She’d also install surveillance cameras in public spaces, and would like to double the “mixed” SPVM patrol teams, where police are accompanied by a social worker.

Martinez Ferrada and Projet Montréal’s Luc Rabouin both proposed investing in body cameras for police officers as a way to hold law enforcement accountable, even though a 2019 pilot project concluded body cameras were costly and ineffective. Officers were permitted to turn off their body cameras “in exceptional cases,” contributing to public skepticism.

Rabouin has promised to protect rooming houses and invest in shelter spaces, and Martinez Ferrada has also promised to invest $30 million annually in organizations and outreach workers and $100 million for emergency shelter spaces.

Transition Montréal’s mayoral candidate Craig Sauvé pledged to invest $30 million annually to address homelessness, including increasing shelter spaces, which would come from taxing wealthy individuals.

Page: City needs more shelters for women

With few shelter spaces and an oncoming winter, Page fears violent altercations between STM constables and vulnerable people could increase. Page says she also worries there’s no efficient way to hold problematic officers accountable.

“You’re pushing someone out of the only place that’s actually keeping them from freezing, or that’s keeping them from having to sleep in a dark alley or an abandoned building,” she said.

She is frustrated with the lack of shelter spaces and medium-term housing, particularly for unhoused Indigenous women in downtown Montreal.

“Predators that hang around (Cabot Square) saddle up to them and offer housing. There are multiple cases right now of young women who have aged out of the Department of Youth Protection with middle-aged drug dealers, because they are like ‘at least he provided a place to stay tonight,'” said Page.

When Page started at Iskweu prior to the move-along order being in effect, her team took her around to different metro stations to meet clients and offer what little resources are available. She says that the increased policing of metro stations can exacerbate the MMIWG2S crisis.

“If people have bad experiences with the STM constables, then they feel that the metro is not a comfortable place, they’re going to go looking for other places,” says Page.

Page says that intervention workers have the training and relationships to keep themselves safe on the job, and law enforcement could work alongside community workers rather than pushing them out of interventions.

“We want to continue to work (with STM constables and SPVM officers). I also really care about their safety and their workers’ rights, having worked in this milieu for a really long time,” Page said.“It’s not safe if you don’t understand trauma, if you don’t understand mental health and if you don’t know the right words to say to somebody. That learning takes years. It’s an entire group of professions on its own.”

While Page acknowledges that metro stations are not appropriate overnight shelters, she does not see enough effort being made to increase shelter spaces and housing to prevent people from using metros in the first place.

“What’s really needed, and what I’m really pushing for, is a woman-centric and LGBTQ+-centric space near Cabot Square. Have it be somewhere where people who are in active addiction can come and stay, but where they can also get support and where they can get more long-term housing.”

Great reporting. One helluva story!