Quebec Schools, Muslim Students, and the “Problem” of Where to Pray

Last year, Education Minister Bernard Drainville banned the use of campus space for prayer. Parents worry their children are taught to be ashamed of their religion.

Every lunch period, Amir slips out of class, puts on his coat and goes to the only place he’s allowed to pray: in the parking lot next to a dumpster.

“Even if it snows, even if it rains, he prays outside near the garbage,” said Yusef*, Amir’s father. “I tell him not to, that he can pray inside and if he gets caught I’ll deal with the consequences. It’s almost like they’re teaching him to be ashamed of his religion.”

It didn’t used to be this way.

Through four years of high school, Amir and a handful of Muslim students prayed in the library with little fanfare. They attend a secular private school on Montreal’s South Shore but, until recently, the administration was flexible.

“Prayer, in our faith, is this moment where you tune out all the stress, all the noise from the outside world and you find peace,” said Yusef, who did not want his real name published for fear of reprisals against his son. “It’s pushing you, all the time, to clear your head, to be honest, to be humble. It’s like meditation, it’s how many of us try to make sense of ourselves in this big world.”

The trouble began last year during Ramadan. That’s when students were told they’d no longer be allowed to pray on campus. There had just been some controversy over prayer space at two high schools in Laval. At the time, Cogeco Nouvelles reported that students were allowed to gather in a vacant classroom after some were caught praying in parking lots and stairwells.

In response to the uproar in conservative media, Education Minister Bernard Drainville denounced this accommodation as going against Quebec’s “values of secularism.” Last April, Drainville issued a directive to Quebec’s public school system banning the use of campus space for prayer.

“Schools are places of learning, not places of worship,” the minister said.

Support Independent Journalism.

Though Amir’s school isn’t bound to Drainville’s directive, they chose to obey it anyway. Even so, the boy’s father wrote a letter to the school asking for accommodation and received one. Amir could pray in school as long as it wasn’t in a group or blocking emergency exits.

But earlier this winter, when Amir went to the room where he usually prays, a teacher was waiting for him. He was then informed his accommodation was no longer valid.

“They took my son to the principal’s office like he did something wrong,” Yusef said. “So even though we already had permission in writing, we applied for another accommodation. It was rejected. I asked my son if he wanted us to get a lawyer and fight this but he said, ‘Look, it’s my last year of high school, I don’t want trouble. I’ll find a place to hide and pray.’

“That’s a huge problem for me. He’s a good kid, he’s not hurting or bothering anyone, he just wants a quiet space for a few minutes at lunch. We’re not asking to turn the school into a mosque.”

Though Yusef asked The Rover not to publish the school’s name, he provided a copy of the latest accommodation request and the principal’s rejection letter.

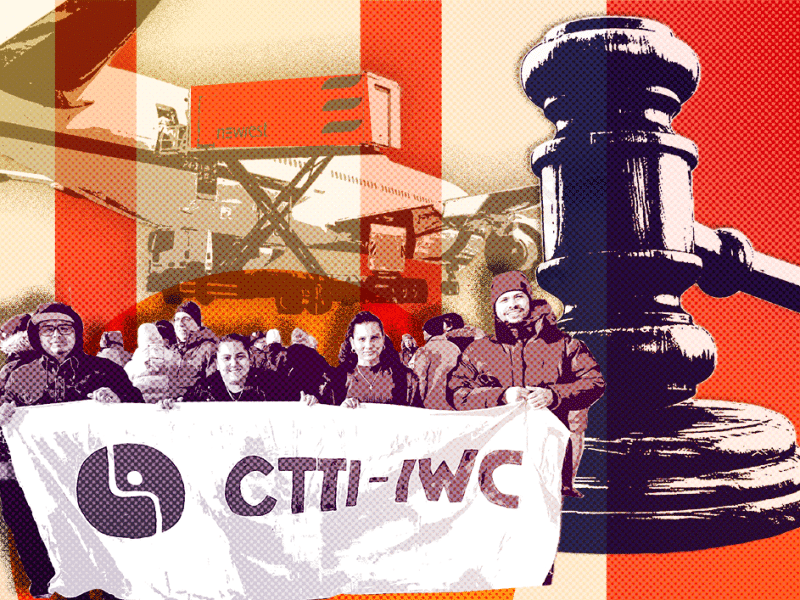

The struggle over prayer space in Quebec schools comes as the province secured a victory in Quebec court Thursday to uphold Bill 21. The bill bans teachers, police officers and judges from wearing hijabs or other religious garb on the job. Though it applies to all religions, a previous ruling by the Superior Court called the law “morally repugnant” and found that it disproportionately discriminates against Muslim women — preventing their full participation in Quebec society.

Thursday’s ruling says that while Bill 21 violates the Charter right to freedom of conscience, Quebec’s use of the notwithstanding clause allows it to bypass those rights. Combined with last year’s directive on prayer space, Muslim families say they feel unwelcome in Quebec.

“When does it stop, when do they stop coming for our rights?” said Samer Majzoub, president of the Canadian Muslim Forum. Majzoub’s group is suing the Quebec government over access to prayer space.

“At least with Bill 21, we’re talking about adults who are old enough to understand this is political. But when you tell a child they have to go hide to pray, how are they supposed to take that? You’re telling them that they’re not welcome in their own school if they take a few minutes to pray. That’s a dangerous message.”

Majzoub and the other parents failed to get an injunction against Drainville’s directive last year but a judge will rule on the matter once it undergoes a full constitutional review. The families’ lawyers will still have to prove that their children’s right to practice their religion doesn’t impose undue hardship on their schools.

“What’s going to make the government’s case hard is that these schools had already worked out accommodations with students,” said Robert Leckey, the dean of McGill University’s Faculty of Law. “What Drainville did was sort of freak out at the idea that schools had already made arrangements by which kids would be given space they could use to pray. He intervened in a situation where schools had already concluded that they were perfectly able to manage.

“It would be different if the students were asking for access to a room 24 hours a day. But the fact that they had already come up with solutions tells you it probably didn’t impose undue hardship on the school. So for Drainville to take this and react how he did looks like more than just a failure to accommodate. You could make the case that this is discrimination based on religion.”

The Office of the Minister of Education did not respond to The Rover’s request for comment.

Majzoub says generations of Muslim students have gone through Quebec’s public school system without seeing their freedom of conscience interfered with and attacking it now sets a dangerous precedent.

“This is a manufactured crisis,” said Majzoub, president of the Canadian Muslim Forum. “There had not been a single complaint in decades and now, all of a sudden, children praying quietly during their lunch break is a problem. We had solutions in place but instead, the Minister inflamed the situation.

“What exactly are these kids doing wrong?” Majzoub continued. “They’re doing their studies, they’re not involved in gangs, they want to take a few minutes to pray.”

Majzoub says he’s afraid Quebec is following in the footsteps of France, which has adopted a series of laws targeting the rights of Muslims to display their faith in public since the 1980s.

The French concept of “laïcité” places the neutrality of the state above an individual’s right to religious freedom. Muslim students aren’t allowed to wear their hijab to school, it is illegal for women to wear the burqa or niqab in public and other limitations imposed by laïcité laws severely limit how people can practice religion outside of their homes.

Legal scholars argue that this crosses the line from secular neutrality to a form of anti-religious prejudice.

But while Mazjoub warns of a continued erosion of civil liberties, Drainville’s government has argued this vision of secularism strikes the right balance between individual and collective rights. Previous attempts at legislating laïcité pushed much further than Bill 21, preventing hijab-wearing women from working in any public-facing government job including nurses, daycare workers and clerks.

Bill 21, on the other hand, limits the ban of religious garb to people in positions of authority: public school teachers, principals, judges, government lawyers, police officers and prison guards. Even so, Yusef worries that it creates two categories of Quebecers and that his family finds itself on the wrong side of that divide.

“My son, he’s a regular teenage kid, he’s obsessed with soccer, he loves his friends, he plays too much Playstation, he can name every statistic of every major soccer player in the world,” Yusef said. “His best friend is a non-Muslim Quebecer, he stays out of trouble at school, he’s the kind of kid any parent would want. It just so happens that he likes to pray at lunchtime.

“I’m not worried about him so much. He’s tough, he’ll stand up for himself. I worry about his little brother. A much gentler kid, someone who might not fight back because he doesn’t want to cause a problem. I don’t want him to grow up thinking he’s a problem.”

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that Bill 21 was upheld in a federal court in Thursday, Feb. 29. In fact, it was upheld in a provincial court. The Rover regrets the error.

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.