Quebec’s New Healthcare Reform Scrambles to Fix a Broken System

Physicians and patients agree that Quebec’s new Bill 2 will drain human care from the province’s healthcare system.

Last January, Eli Varvaro started to wake up in the middle of the night from a sharp pain in her torso, so intense that she would end up on the floor in excruciating pain.

Each episode would last one or two hours, and she convinced herself that it just wasn’t that bad. Then one summer morning in June, the pain came back, and this time, it didn’t go away.

Varvaro asked her sister to drive her to the ER, and when they got there, Varvaro fainted from the pain. She felt pressure in her torso, as if an inflated balloon was inside her, and every exhalation made her scream. “I was swearing a lot. I remember because later I was apologizing to the nurses for swearing,” she says.

“Everything took six times longer than it should because it was clear that everyone was running around putting out fires,” she says.

After hours of waiting, the ER physicians found gallbladder stones in Varvaro, and she had the surgery to remove them the next morning. One of the most common causes for surgeries at the ER, gallbladder stones can be debilitating.

Varvaro says that if she had access to a family doctor, someone she could’ve seen back in January when the pain first began, she might have avoided the whole ordeal. A physician could have recommended a dietary change to help reduce bile build-up in her gallbladder, which led to the stones. She could also have had hormone testing to see if that was a factor in the issue, which is the case for many women. All kinds of preventive measures could have been done for this very routine issue, says Varvaro.

The last time Varvaro saw a family doctor was when she was a teenager, still living with her parents. She has been on a waitlist for a family doctor for five years.

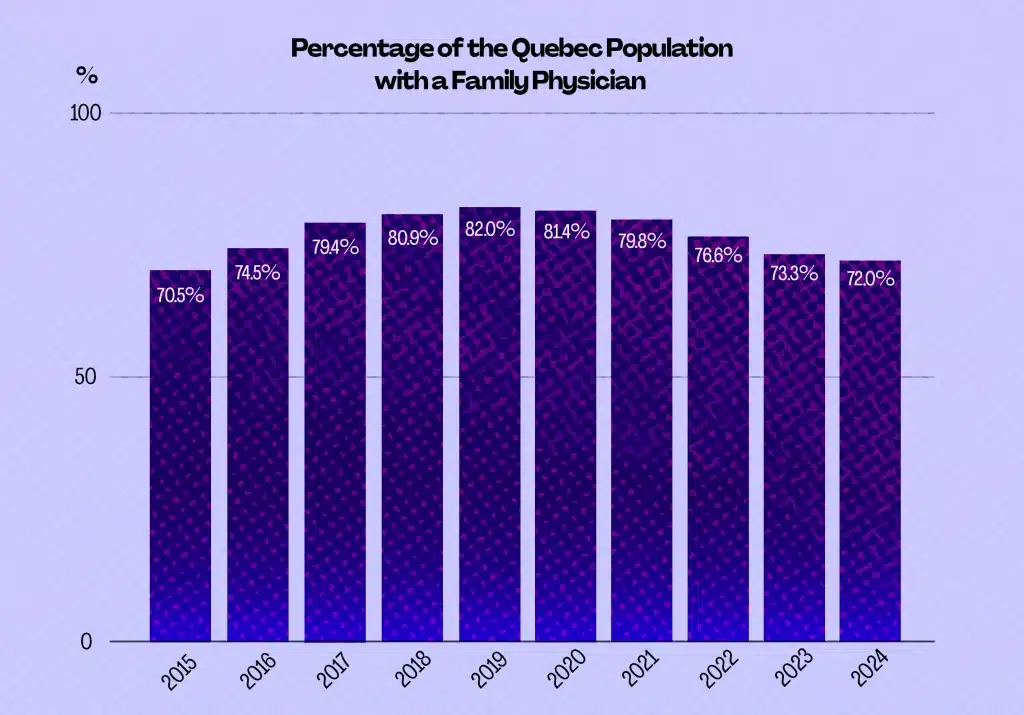

She has developed a mentality common among people who struggle to access healthcare: the one that convinces them that their health problems “are just not that bad” until they become impossible to ignore. Like Varvaro, more than 1.5 million Quebecers don’t have a family doctor and often choose to push aside their non-life-threatening health issues simply because they have no other choice.

As a solution to get more access to family doctors, the governing Coalition Avenir Québec (CAQ) introduced new legislation, Bill 2, which notably sets new targets for the number of patients family physicians should see per year and ties their pay to capitation, a fixed price based on the number of patients assigned to them.

There has been significant pushback within the medical community about how this legislation will affect a public healthcare system in Quebec that is already strapped for resources. Some medical associations like La Fédération des médecins omnipraticiens du Québec (FMOQ) argue that the bill fails to consider patients’ views and experiences and to build a healthcare system that works for patients rather than the government.

Without more family doctors, specialists, and nurses, experts argue that the new targets will force practitioners to see more people but won’t give them enough time to provide real care and attention.

The law is supposed to be enacted by Jan. 1, 2026.

Support your local indie journalists.

Understanding the bond between doctor and patient

After finishing her degree in international relations and a master’s in international law, Pascal Breault switched careers to become a physician. She now works as a family doctor at the Hochelaga-Maisonneuve local community services centre (CLSC).

For her, the most significant part of family medicine is the relationship between the patient and the physician — a relationship that grows over time and transcends medical issues, says Breault.

When a patient arrives in her examination room, she knows something is going on in their lives, beyond their health issues, just by looking at them.

In her eyes, Bill 2 will affect this relationship. “There is just no way that this bond and the importance (it has) is recognized by the law,” says Breault.

One of her main concerns is the classification of patients into three colour categories: red, yellow and green, depending on their medical record. This means that the patients classified as red and yellow will have priority when accessing the healthcare system.

“We cannot only mitigate the situation and the needs of someone regarding their medical diagnosis. We are taught in university to consider the broad biopsychosocial aspect of anyone,” explains Breault.

This colour-coded system will also affect physicians’ financial compensation. Doctors who serve “green” patients will receive less compensation than other physicians who care for more urgent cases.

Green is the colour of youth, says Breault. In the green category, even patients who must attend regular appointments, such as kids or pregnant women, will face multiple challenges when accessing healthcare.

This system will also exacerbate the difficulties already faced by populations in marginalized neighbourhoods, like Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, in reaching healthcare professionals.

“They deserve quality and time, but the system, the way it is presented in the law right now, just doesn’t match reality,” says Breault.

“Why are the patients in the emergency department? It’s because the system is really complicated. When a patient goes into the emergency department waiting room, they sit, and they know they will be seen.”

Claudel Desrosiers has worked as a family doctor at the same clinic in Hochelaga-Maisonneuve as Breault for the last five years. A lot of the patients she sees have a history of living in poverty and often have complex mental health issues like post-traumatic stress disorder.

One of her patients with long-term mental health issues has been struggling to afford groceries because of the increased cost of living. She managed to live off cheap, hyper-processed food for a while because she couldn’t afford anything else. This, of course, has a compounding effect on her physical and mental health. But recently, she found better, more affordable accommodation, so she could finally have access to healthier food options. She recently told Desrosiers that she’s doing much better now simply because she can eat fruits and vegetables.

The myriad social problems that affect people in a neighbourhood like Hochelaga-Maisonneuve, such as food affordability, housing, and climate, often fall to the healthcare system. But these are symptoms of larger issues that cannot be treated in a clinic — they are matters of municipal and provincial policy.

“I cannot, in my office, fix the housing situation. I cannot fix the pollution that my patients breathe on a daily basis,” says Desrosiers.

Many of her patients struggle to find a stable housing situation, and most don’t have private insurance to pay for a therapist, which they often need. The public system offers these patients a few meetings with a social worker, which doesn’t help them understand and deal with the complicated issues like PTSD and chronic pain.

“The only way of access to a professional that they get is me — what they need is not me. They need a psychologist, they need a physiotherapist, and those professionals are not within the public healthcare system,” says Desrosiers.

At Desrosiers’ and Breault’s clinic, they see about 13,000 patients a year. With Bill 2, Quebec’s government plans to assign “orphan” patients to existing care providers, such as Hochelaga-Maissoneuve’s CLSC.

According to Desrosiers, Bill 2 will require them to see 29,000 patients by the end of 2026 — more than twice the clinic’s capacity. Right now, 30 doctors work at the clinic, and there will be no additional support to handle the influx of new patients. On top of that, the clinic’s only physiotherapist will soon be on leave for three months, with no replacement.

“We don’t have the resources that we need to work with more than half the patients that come see me on a daily basis,” says Desrosiers. She says that the law does not address the profound problems that family medicine is already facing throughout the province, yet it asks family doctors like her and Breault to do more and see more patients with only bare-bones support.

The problem with standardizing public healthcare

“The bill is built around statistics, objectives, and goals. Administration requires supervision; it requires audits and statistics, but a patient requires care,” says Breault.

When Breault isn’t in her examination room at the CLSC, she is at Santa Cabrini Hospital as a hospitalist doctor.

Physicians like her, with less than 15 years of practice, must commit to 12 hours of specific medical activities (Activités médicales particulières, AMPs) per month. In addition to their clinical practice, family doctors are required to work on-call shifts in emergency rooms, residential and long-term care centres, and detention centres, among other settings.

Breault usually does her AMPs every four weeks. At the hospital, she cares for 20 patients per day. Though her schedule is demanding because she must be available at any time, she says she likes her work.

She is aware that the mandate in Bill 2 to receive more patients as a family doctor will increase her workload and the hours she must work to provide healthcare for her patients at the CSLC.

“We provide amazing care. All my colleagues, all the doctors I know, are heavy workers. We can handle a lot,” says Breault.

However, she believes the rate of burnout will intensify, not only because of the increase in workload, but because of the loss of sense and meaning in her work due to how Bill 2 is shaping the practice of family medicine: a system built around numbers, statistics and goals.

“The perfect recipe for burnout is the lack of understanding between what you need to do and what your boss requires you to do, and the government is doing that perfectly,” says Desrosiers.

Breault thinks that in reality, the healthcare system outlined in Bill 2 isn’t about the patient’s needs, but rather the government’s.

“The bill is built around statistics, objectives, and goals. Administration requires supervision; it requires audits and statistics, but a patient requires care,” says Breault.

Leigh Hoffman, who worked as a registered nurse in Quebec for 4 years, says she watched the province’s public healthcare system degrade rapidly from 2021 until she finally decided to leave at the beginning of this year to work in British Columbia.

She says that even before Bill 2, the 2023-2024 transition for Quebec’s public healthcare system to be managed by a centralized agency, Santé Québec, was a move she knew would make her life as an ER nurse significantly more difficult. It promised outcomes similar to those in Bill 2, to improve access to primary care. According to Hoffman, it did nothing to improve the day-to-day experience of people accessing services or the material realities of those providing those services.

The new structure only added more bureaucracy as a result of the internal restructuring. Hoffman had new managers and different people to answer to, and more paperwork to do while adjusting to a completely new system.

“I think (Bill 2) is like a direct consequence of the move to Santé Québec,” says Hoffman “It’s this idea that they can centralize all care and standardize it in a way that is naïve to the reality on the ground. There are certain standardizations you can have in health, but the level to which they’re trying seems like it’s coming from a business model and not from a public health model.”

Other practitioners in Quebec are feeling similar frustrations. Just a few weeks after Bill 2 was passed, nearly 400 doctors in Quebec had applied to practice medicine elsewhere in Canada. Four head physicians at the Outaouais health authority resigned over the changes in the law. In Montreal, one of the largest family clinics lost nine of its 51 family doctors due to the bill.

Support your local indie journalists.

Quebecers funnelled into the private system as a last resort

When Varvaro went home after her gallbladder surgery, a wave of panic rushed through her, and her body temperature shot up all over. She thought she could be dying and called 911.

When she was patched through to a nurse, they went through every possible side effect she could be having after the surgery, and they figured out she was having a panic attack. The nurse told her it was normal for her body temperature to fluctuate after surgery and told her to stay somewhere cool. But Varvaro knew she needed to have consistent care after her surgery as she was recovering.

“Ultimately, I caved in for the time being, and I’m seeing a private family doctor just so that I have someone who can follow through with my care,” says Varvaro.

Countless Quebecers have made the same choice: to bite the bullet and pay more for a private doctor or specialist rather than wait weeks, months, or even longer to be seen in the public system, risking their health.

Megan Mills, who recently went to the ER for debilitating oral pain, didn’t choose to go private, but the price to pay for a broken public system was steep.

At the ER, she was triaged as an urgent patient early on, but she waited hours longer than she should have. In the waiting room, a man suffering from a mental health episode had to be escorted out of the space two separate times; another woman was vomiting in pain, someone else had CPR performed on them in the waiting room, all while Mills sat alongside them, crying in pain. After waiting for hours, she asked the nurse whether she had been triaged incorrectly, and after talking with her, Mills understood the delay was because the hospital was understaffed.

“I believe that the government is manufacturing consent for private healthcare by making (public healthcare) such a non-functioning system,” she says. “It’s just really frightening to think this should be the government’s responsibility to set an appropriate budget and to make sure that people are trained appropriately and are doing jobs that are within their capacity. That responsibility is now being pushed onto individual physicians.”

What’s to come in the next year is uncertain, experts say

Damien Contandriopoulos, a professor of public health at the University of Victoria who previously taught at Université de Montréal, says that while physicians are sounding alarm bells about how the law is a disaster, the solution isn’t to throw it out completely.

“There would be glitches, and there are many disputable elements in the bill, but currently, access to care in Quebec is really bad,” said Contandriopoulos. “There are a very large number of people who do not have any way to get to a family doctor, and the system is also deeply unfair: if you are older, sicker, and poorer, your odds of getting a family doctor are much lower. So just maintaining this status quo is not really something anyone should be looking at as a big win — It’s not.”

He adds that in the context of a pre-electoral year, as physicians are exerting significant pressure for the legislation to be changed, he wouldn’t be surprised if the law is watered down so much that it doesn’t really change much.

If the law goes forward as written, Contandriopoulos says it’s not great news, but if a change isn’t implemented, Quebecers will be stuck with the system that’s in place, which is not much better.

Some of the proposed changes, like shifting the compensation model to capitation rather than a fee per service, could in fact be useful, according to Contandriopoulos. He says it would incentivize team-based care where doctors delegate patients based on their needs to other medical professionals in a clinic rather than taking on every patient themselves.

“You can’t stop the system and reset it— it needs to be seamless, transforming that funding model,” Contandriopoulos said “RAMQ is going to suddenly stop receiving fee-per-service billings and instead send out checks for enrollment based on what timeframe? All of this is going to take time. So when you look at 11 months before the election, maybe things are going to be implemented, maybe not.”

For Breault, problems in the healthcare system are due to temporary measures governments have implemented before, such as the Primary Care Access Point (GAP), which don’t address the issue in the long term. In her eyes, the GAP was helpful to register and provide access to thousands of orphan patients, but, as Breault says, it was supposed to be a short-term measure.

“There were many critiques regarding that system,” says Breault. “It was still an innovation and an improvement, but ultimately, the biggest challenge and the biggest critique we can provide is that patients didn’t have their say regarding the way it was put in place.”

If the question was supposed to be how to address access to healthcare, the appropriate response isn’t Bill 2, says Breault.

“If you want to improve things, you need to really consider the root of these things,” says Breault. “And the root of the healthcare problem isn’t medical care. It’s too late when they arrive at my examination room. It’s even too late when they go to the hospital.”

In the midst of every crisis lies a great opportunity, says Breault while reflecting on the current state of Bill 2. For her, this is a great moment to have a proper discussion, as a society, about Quebec’s healthcare system, especially to amplify patients’ voices and experiences and finally shape the system around them.

This optimism is accompanied by uncertainty, since the instructions for implementing the changes proposed by Bill 2 aren’t clear, and the Quebec government is still trying to answer questions the physicians have raised.

“What’s next? How should we face that?… We are really clueless about how it is supposed to work.”

Did you like this column? Share it with a friend!

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.