Rent Increases Set to Worsen the Housing Crisis

Experts warn that homelessness continues to grow as Quebec’s housing tribunal proposes a new way to calculate rental increases.

When Lyn Lee started working with a tenants’ rights group five years ago, she never imagined that part of her job would be accompanying folks to the emergency room.

But faced with an out-of-control rental market that’s pushing hundreds of Montrealers onto the street each year, some of Lee’s clients are buckling under the pressure.

Sometimes she takes them to the hospital.

“It’s catastrophic,” says Lee, a community organizer at Comité d’Action des Citoyennes et Citoyens de Verdun (CACV). “I’m not supposed to work at a crisis intervention centre, I’m supposed to work at a tenants’ rights association. But we deal with a lot of mental health issues stemming from the stress of evictions. So I spend time waiting with people at the Douglas (Mental Health University Institute), at the hospital, a community clinic, in court.

“We’re not funded to provide mental health services, we’re not funded to be a crisis intervention centre. But what other choice do we have?”

Support your local indie journalists

Lee’s concerns aren’t unfounded. In 2019, two months after receiving an eviction notice from the new owners of his building, a 73-year-old Verdun man took his own life. The owners, a limited liability corporation, offered a cash settlement to the elderly man so they could get him out of the rent-controlled unit and flip the property.

In the end, the tenant’s health declined rapidly after he received the notice. Faced with the prospect of leaving his home of nearly 50 years and being pushed into a brutal rental market, he chose to die. That’s according to a coroner’s inquest into the man’s death.

Lee expects her already busy schedule to ramp up now that Quebec’s housing tribunal (TAL) published its recommended rent increases for this year. Using a new formula that factors in school taxes, variations in insurance cost and inflation, the tribunal determined that a fair increase for renters would be 3.1 per cent. That number jumps to 5 per cent for tenants whose landlords carried out “major renovations” to the unit after Jan. 1.

This follows last year’s whopping 5.9 per cent increase, which capped off a six-year period that saw rent jump by 71 per cent across the island of Montreal.

Those years coincide with a dramatic increase in the city’s unhoused population, which grew by roughly 33 per cent between 2018 and 2022. And while the last official “homeless count” put Montreal’s homeless population at just under 5,000 in 2022, two sources inside city hall say that number has grown by at least 1,000. They say it could be as high as 9,000 when you count invisible homelessness — people couchsurfing, sleeping in their cars, or squatting.

“I cannot think of a harder period for renters in Montreal than these past five years,” said Steve Baird, a community organizer with the Coalition of Housing Committees and Tenants’ Associations of Quebec, also known as RCLALQ.

The old rent increase formula asked landlords to factor in that year’s rate of inflation but now they get to use a three-year average. Which means that even though inflation has come down in Canada this past year, tenants are still on the hook for the previous two years of abnormally high inflation.

Baird says changes to the way Quebec’s housing tribunal calculates increases will only make things worse.

These policies are the brain child of Quebec’s former housing minister France-Élaine Duranceau, who made a career out of real estate speculation before joining the Coalition Avenir Québec in 2022. In 2023, Duranceau had to apologize after famously declaring that tenants should “invest in real estate” if they didn’t want to face rent increases.

That same year, an investigation by Quebec’s ethics commissioner found that Duranceau used her position as housing minister to “abusively favour” her former real estate partner by giving her priority access to the government.

Groups like CACV and RCLALQ say the financialization of Montreal’s housing market has played a massive role in rent increases. The median price of a home in Montreal jumped from $340,200 in 2015 to $630,000 last year. But the profits from the city’s real estate boom have disproportionately benefited a fraction of Montreal’s homeowners.

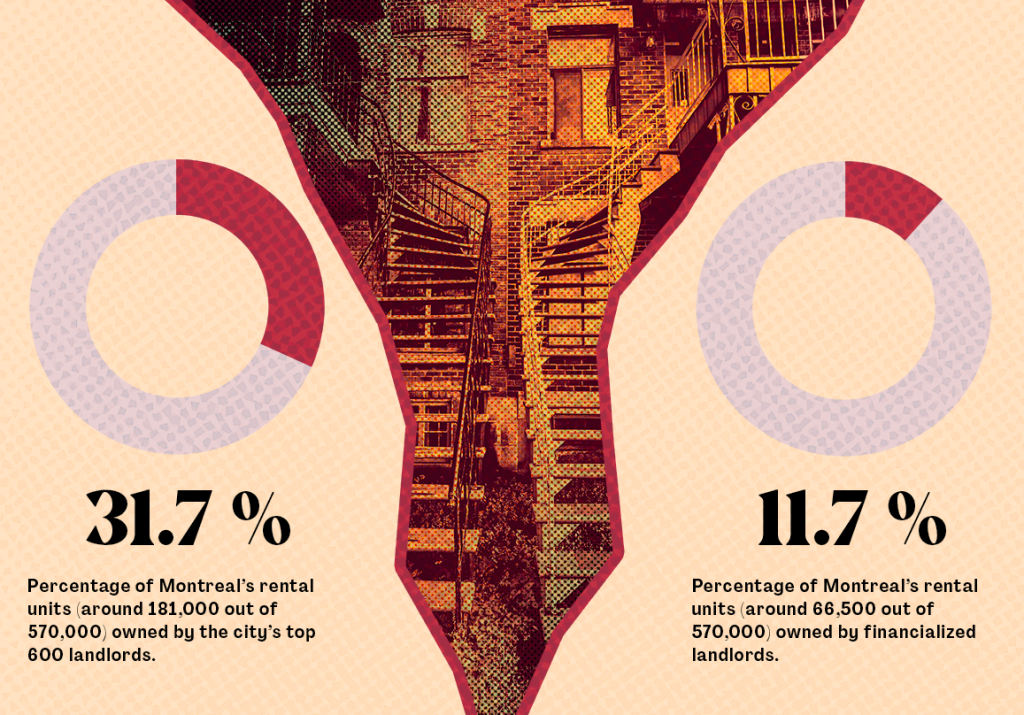

In Montreal, where a majority of residents are renters, the top 600 landlords own 31.7 per cent of the city’s 570,000 rental units. That’s according to a 2024 study published in the Journal of the American Planning Association. To see a return on their investment, these corporate landlords have resorted to a series of borderline and sometimes outright illegal tactics to evict tenants and increase rent.

“Ever since the (Montreal) boom really took off, there’s been a critical consciousness that making money off people’s basic need for shelter is an inherently unethical thing to do,” said Fred Burrill, a housing organizer and professor of history at the University of New Brunswick.

“There is more of a willingness to entertain the idea that tenants need to organize and resist. Anecdotally, I’ve seen middle income people who would never entertain the idea of refusing a rental increase start to resist. And this will not change without a consistent and collective resistance movement.”

In 2024, Duranceau imposed a three-year moratorium on evictions where landlords oust tenants so they can subdivide or enlarge a dwelling. Once the landlords modify the dimensions of their rental unit, they can dramatically increase rent. These “renovictions” were common in rapidly gentrifying neighbouroods like Verdun, where groups like CACV are struggling to keep up with demand.

“We used to be able to have a few days a week where people could walk in without an appointment and get advice on evictions, rent increases and all that,” said Lee. “But now it’s by appointment only. These tenants don’t have access to lawyers, they’re not going to get justice. So we’re the next best thing, I guess. We’re going to see an even bigger bottleneck at the renter’s tribunal this year, it’s out of control.”

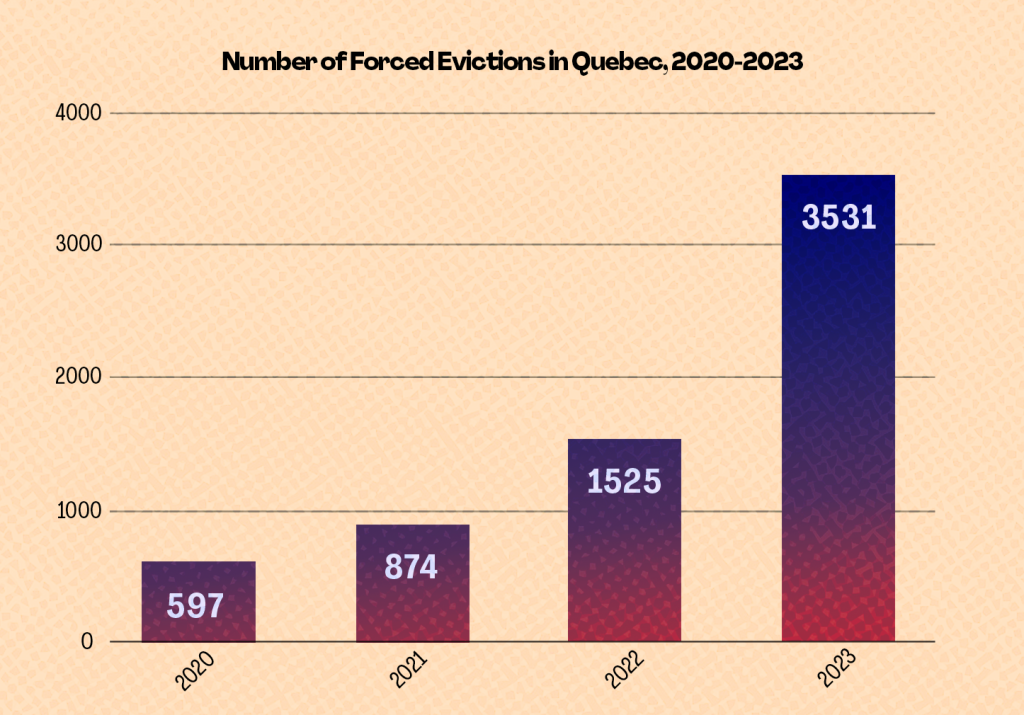

Duranceau’s moratorium came on the heels of a report, by RCLALQ, that found evictions in Quebec had reached an all time high, with 3,530 tenants filing complaints with the TAL that they’d been forced out of their homes between July 2022 and June 2023. When reached for comment, a representative from the TAL said it does not keep comprehensive data about evictions and therefore could not say if things have improved.

In the first budget tabled by new Montreal mayor Soraya Martinez Ferrada, the city injected an extra $3.4 million in funding to the municipal housing authority — the Office municipal d’habitation de Montréal (OMHM). Last year, the OMHM helped 471 households find a dwelling and provided services to some 2,400 households in total, according to city spokesperson Camille Bégin.

Martinez Ferrada argues that one of the main factors driving the rental crisis is a lack of supply. But this ignores the vacancy rate for apartments in the city was 3.1 per cent last year, according to data from the Canadian Mortgage and Housing Commission (CMHC). That’s nearly two times higher than it was in 2020.

In reality, the rental crisis is one of haves and have-nots. For people who can afford a dwelling priced between $1,800 and $2,800 per month, the vacancy rate is 6 per cent. But that number drops to 1.5 per cent for anything $1,300 or lower. The problem isn’t the overall supply, but the supply of affordable units.

There is a proposal from three private developers to build 2,500 housing units in Montreal for about $300 million. Once the units are built, the city will spend upwards of $15 million a year on mortgage payments for those homes. But at least one of the developers, Cogir, has a history of trying to evict vulnerable tenants.

In the end, the partnership between Montreal and private developers amounts to a public subsidy for private profit, argue Burrill, Lee and Baird.

“I understand that investors want to recoup their investment, that’s how capitalism works,” said Burrill. “But maybe if your business model requires people to spend upwards of 50 per cent of their monthly income on rent, you made a bad investment.”

Did you like this article? Share it with a friend!

Thank you for this informative article.

There needs to be more open discussions on renters rights!

Protest if need be!