Revitalizing the Creeks in Kahnawake

The creeks of the territory carry in their streams the memories of the community. Even though their waters flow slowly due to their deteriorated state, the Kahnawà:ke Environment Protection Office seeks to restore the creeks and revitalize the community’s connection with these ecosystems.

Kahionhanó:ron Canadian and Tekaronhiané:ken Alfred, members of KEPO staff, removing invasive plant species from the North Creek. PHOTO: Courtesy KEPO

Carlee Kawinehta Loft was visiting her uncle when she saw a muskrat come out of the creek and start to fight her uncle’s dog.

She thought the scene was terrifying — because the muskrat bit part of the dog’s ear off — and interesting — she got to see this animal living along the creek’s waters — at the same time.

The North Creek, or Whákeras Creek, passes through the heart of Kahnawà:ke (Kahnawake). It is one of the four major creeks that flow through the wetlands, forests, agricultural fields, and heavily developed areas of the territory.

Loft is the Policy and Outreach Coordinator at the Kahnawà:ke Environment Protection Office (KEPO). She didn’t grow up along the creeks, but those streams of water are part of her history and memories too. She remembers going to her uncle’s place and swinging with a rope hanging from a tree, trying her best not to fall into the North Creek.

The state of Kahnawake’s creeks has been deteriorating. They have lost their biodiversity and, in some parts of the community, the water no longer flows or is affected by invasive plant species.

In 2023, KEPO launched the Entewahnekahserón:ni’ project, which means “We are rejuvenating the water” in Kanien’kéha, the Mohawk language. This initiative seeks to improve the habitat of Tekakwitha Island — created artificially after the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway — Recreation Bay, and three creeks: North Creek, Little Suzanne River, and Suzanne River.

Before this project started, KEPO’s field staff visited the creeks and aquatic habitats in the territory to monitor and conserve them. While taking water or fish samples, community members approached them to share their memories of the creeks.

“It was really powerful to perceive those feelings that people had towards the creek,” says Tyler Moulton, a biologist at KEPO.“You could really feel that sense of loss because it has become quite a bit less natural over the years,”

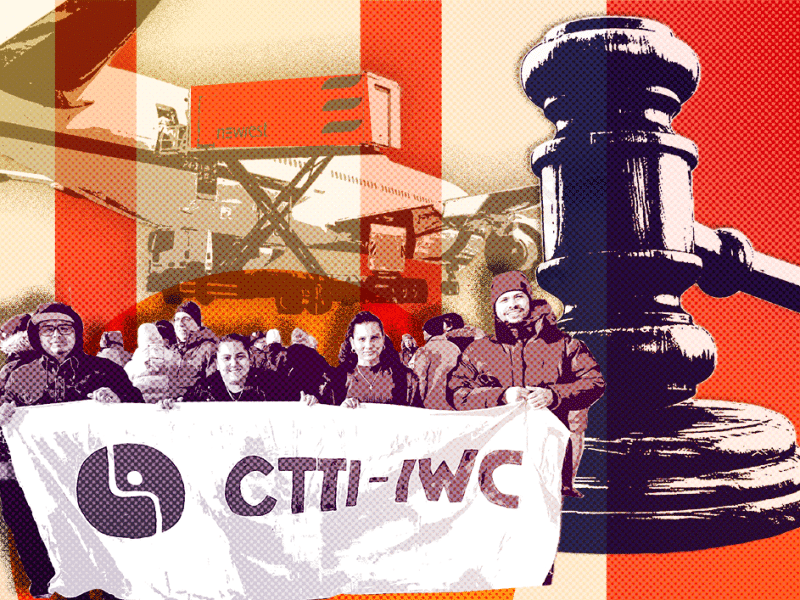

Support your local troublemakers!

Years ago, people used to fish in the creeks. Others used the streams to wash corn in a basket every weekend to prepare cornbread. For some kids, the creeks were a means of transportation from one end of the community to the other with makeshift rafts they created. During winter, people skated in the frozen waters. Some still do in areas where the North Creek still has enough water.

For KEPO’s team, these stories were an indicator of the previous healthy state of the creeks. The memories were the fuel to start the restoration of these bodies of water, but especially, the revitalization of the community’s relationship with them.

“These are stories of a time that we can’t really revisit, but those stories can be passed from person to person. That is also a part of the creek that we want to make sure it stays alive, not just the environmental aspects,” says Moulton.

Before the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway, the riverfront was a gathering place for many community members and a livelihood for others.

Kahnawà:ke before the construction of the St. Lawrence Seaway. PHOTO: Courtesy KEPO

“We had fishermen, a lot more fishermen. This was their life. Even if you weren’t a fisherman, families would go to the river. They would go to the waterside and wash their laundry,” says Loft. “They would spend the whole day out there having picnics, catch up with people and look out for each other’s kids if they headed off somewhere. There was a sense of community around the water.”

The St. Lawrence Seaway was built to connect the Great Lakes to transatlantic shipping along the river. Its construction started in the summer of 1954 and ended in 1959. This process was traumatic for the community. The federal government expropriated 1,262 acres of land in Kahnawake. Many families in Ontario and Quebec were relocated, and others were evicted from their houses.

The Seaway project left a mark in the community due to the lies, confusion, empty promises and forced evictions. During the process, a lawyer representing 13 residents argued that the Seaway Authority was using pressure tactics and intimidation by taking bids on expropriated buildings before the settlement and sending notices of sale.

“Elders in our community have talked about it for generations. It was so long ago but they remember that their whole lives changed after that and that there was a feeling of helplessness because there was nothing that could be done,” Loft says.

Today, community members must take a 20-kilometre detour by car to the nearby town of St. Catherine to access the river. PHOTO: Courtesy KEPO

The clay soil and riprap stones from the seaway construction were placed on a series of islands that existed in Kahnawake, which ended up creating what is known today as Tekakwitha Island and the Recreation Bay. The community has adapted to the conditions of the environment and found ways to use the island and the bay for paddling, fishing or swimming, among other activities.

Wildlife also adapted to the rocky soil. Nevertheless, KEPO continues to work on restoring this place by removing contaminated soils — which are a hazard for the community and wildlife — creating turtle nesting sites, and increasing the water flow to improve fish habitat.

The Seaway’s construction also changed how the community could interact with the river by blocking their access. What was once a 10-minute walk to swim or fish on the riverfront turned into a 40-minute drive. This also affected the health of the creeks and the relationship the community had with them. Urban development around the creeks also affected these ecosystems. Some culverts are too small for fish to pass, and digging and dredging changed the meanders of some of them.

“Now, instead of nice, flowing, clean water of the creeks, you have the seaway, which is much much slower moving, deeper water. There’s not a natural shoreline. It’s all big boulders,” says Moulton.

The revitalization of these ecosystems starts with a community-centred program, the North Creek Visioning Project, where the KEPO’s team collected testimonies by phone calls and messages through social media about the community’s memories of the North Creek to construct a collective memory. Nine elders were interviewed about the significance the creeks had to them in the past, what they mean to them in the present and what they hope for their future.

They shared memories about playing around the creek when they were kids, hunting muskrats or seeing different types of fish, like sunfish, in the streams.

The result of these interviews is a documentary called We Are Rejuvenating The Waters that brings these memories to the present to involve the community in the restoration process of the creeks. It’s a call to the next generations to love and protect the river as their ancestors did.

“We’re not going in there and just doing a one-time construction project. It’s about improving some of the infrastructure around the creeks, but also about having this community stewardship of people who live along the creeks, taking care of it and understanding how to take care of it better and relearning how to do that,” says Tyler.

Brandon Atéhrhanonhne Rice, Project Support Technician at KEPO, releasing fish in the North Creek. PHOTO: Courtesy KEPO

As humans, memory gives us a sense of self and connects us to our environment. Rivers and creeks also have memories. They can remember their old meanders and the areas they occupied. Water is part of the history of humanity and our memories too. Even though our respect and sense of responsibility to take care of aquatic ecosystems have been damaged, humanity’s relationship with water can still be revitalized, as it’s happening in Kahnawake.

In Kanien’kéha, Kahnawà:ke means “By the rapids” or “On the rapids,” depending on who you ask, Loft explains.

This connection and respect for aquatic ecosystems is still in the territory. Some members of the community are engaged in the project and contribute with their opinions to elaborate the community-centred restoration plan, others put their boots and gloves on to remove invasive plant species during the cleaning sessions of the creek.

“The great thing about our community is that even if they’re a bit further removed from the history of the creek, once you start talking to them about what it was and how it used to be, that care is just there,” explains Loft. “There is a respect for water, a connection and a deep understanding of what it means for our community to be separated from the water that is a vital part of our life, specifically the St. Lawrence Seaway cutting us off from the St. Lawrence River.”

Did you enjoy reading this article? Share it with a friend!

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.