The Death of an Immigrant

After six months of search parties, rumours and a police investigation that went in circles, Eduardo Malpica’s body was found in the St-Lawrence River last week.

Eduardo Malpica fought his way out of Peru during a time of unimaginable political violence. His body was found in the St-Lawrence River last week.

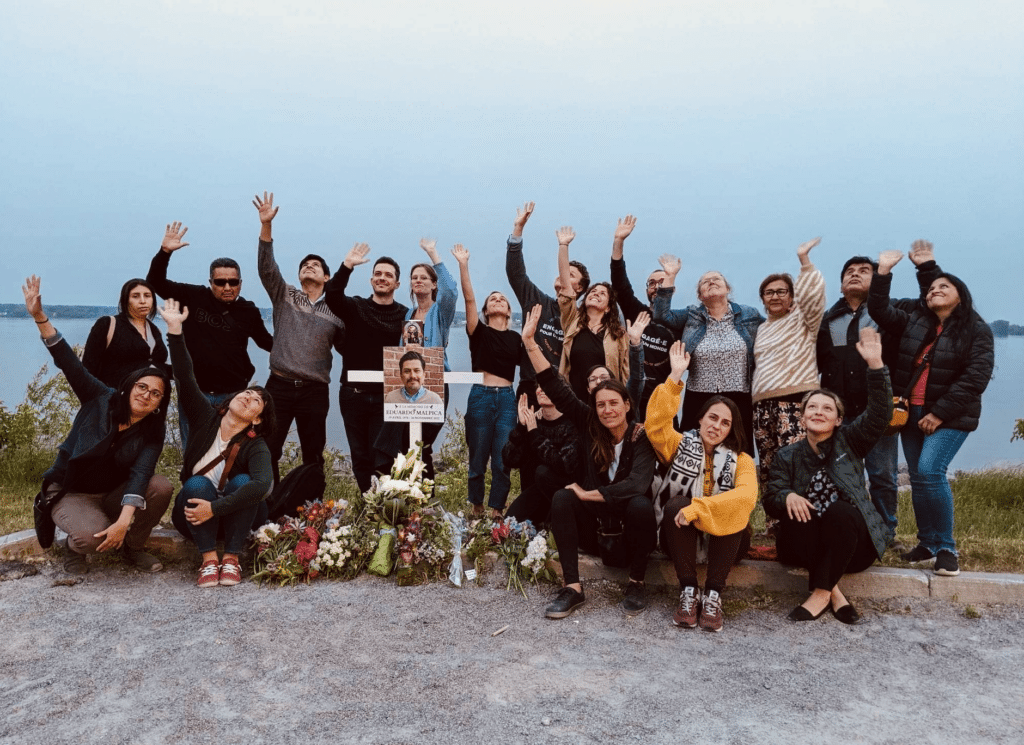

Mourners gathered in Trois-Rivières Monday to commemorate the life of Eduardo Malpica. PHOTO: Courtesy Chloé Dugas

Eduardo Malpica was 12 when his father left the family in Peru and set out for Quebec.

He had no choice; the country was descending into a civil war marked by forced disappearances and death squads. His job as a currency trader meant he carried stacks of cash through the streets of Lima every day. At the height of the violence, one of his colleagues was ambushed, robbed and left to die in an alley.

This was no place to raise children.

So once he crossed the border into Canada, Malpica’s father Pedro claimed refugee status and worked for five years to get his wife and kids over.

Support independent journalism: Subscribe to The Rover

Malpica’s character was forged in the struggle of those long years. Now the oldest boy in the household, it was his duty to help provide for his mom and baby sister. He sold pencils and other knick knacks in the capital city, taking what little he earned back to the one-bedroom flat they shared.

One Christmas Eve, after saving up enough change to buy his family presents, Malpica was beaten and robbed on his way home. That could have broken him but instead he pressed on and when the three of them finally made it to Canada, it was Malpica’s time to thrive.

He buried himself in his studies, going from a 16-year-old who couldn’t speak a word of French to an ace student at Université du Québec à Montréal in just a few years. By the time he turned 44, Malpica was living the perfect immigrant story; a sociology professor who shared a home in downtown Trois-Rivières with his loving partner and baby boy.

Malpica disappeared last November after being attacked in a Trois-Rivières bar, dragged onto the pavement and sent into the cold night without his coat or wallet.

After six months of search parties, rumours and a police investigation that seemed to go in circles, Malpica’s body washed up on the shores of the St-Lawrence River last week.

It may seem like this will finally bring his family closure, that they’ll be able to start healing and get back to some semblance of a normal life. But with so many questions still unanswered, the confirmation of Malpica’s death is just the beginning of a struggle for truth that could last years.

***

Chloé Dugas keeps a shrine to her partner Eduardo Malpica. PHOTO: Chloé Dugas

“Today I woke up feeling like I could change the world, Cholita!”

Alejandra Zaga Mendez’s voice shook as she read the message out loud. For years, Malpica would send these annoyingly positive texts to her on Monday mornings.

Messages like “Happy Monday!” or “Vamos que vamos!”, a sort of rallying cry against the drudgery of another workweek. That may seem corny but it was never insincere. It was Malpica’s way of letting Mendez know he cared.

They were Peruvian immigrants who found each other in a place called Quebec. Over the years their group expanded to include other Latin American expats seeking connection in a foreign land. Within this tight-knit circle, Malpica took on the role of big brother, doting over everyone whether they wanted him to or not.

“On Thursdays, he’d write to us to say his throat was feeling dry. That was his way of asking if we wanted to have a drink,” said Mendez, who remained close to Malpica until the bitter end. “He’d show up to my apartment with a bag of chips and a case of beer and we’d laugh. Now that he’s gone, these messages are a part of him I can keep: his words.”

Mendez sat at a patio bar in Trois-Rivières Monday, scrolling through these digital fragments of a man she loved dearly. In a few hours, Mendez would attend a vigil in his honour, the first public gathering for Malpica since his body was discovered last week.

As she prepared for an emotional night, Mendez spent the afternoon with Malpica’s widow, Chloé Dugas, letting the reality of his death wash over them.

“Sometimes I worry I’ll forget his voice,” Dugas said. “It was the voice of the love of my life, it was the voice of the father of our child. It’s this tiny piece of him I can’t bear to lose.”

Since he went missing last fall, the conversation around Malpica has focused on the violent circumstances leading to his disappearance. And with good reason.

The last confirmed sighting of Malpica was on Nov. 26 in downtown Trois-Rivières, where he lived and worked as a college professor. He was out celebrating with colleagues at a bar but after they left, things took a nasty turn. Malpica, who stayed behind, went from holding a lucid conversation to barely standing upright.

Sometime before 2 a.m, a group of white men attacked Malpica, forced him outside the bar and threatened him. They claim he made unwanted advances towards a woman in their group. But instead of allowing the authorities to deal with the situation, the bar employees let Malpica leave on foot, without his coat or wallet.

Six months later, a fisherman found his body floating along Beauport Bay, some 140 kilometres downriver from the port city of Trois-Rivières.

Malpica’s friends believe his drink was spiked with GHB — a debilitating narcotic known as the “date rape drug.” GHB attacks are so frequent in Trois-Rivières that four months before Malpica’s disappearance, downtown bars and clubs started giving people plastic covers for their drinks, beefing up security and alerting employees to be on the lookout for predatory behaviour. Two patrons who were at the bar the same night as Malpica claim they were drugged.

The police were aware of the possible druggings on the night of Malpica’s disappearance because one of the alleged victims told them about it the following day. It took two months for them to return her call.

Instead, investigators initially claimed Malpica’s case was one of “voluntary disappearance,”, that he essentially abandoned his family without so much as a call or text message. They stuck to this theory for months even though there wasn’t a trace of evidence indicating Malpica was still alive. By March, they settled on a new version of events: Malpica was so ashamed of his actions at the bar that he stayed in the cold all night and threw himself in the river the following day.

Lost in this conversation about that awful night is Malpica himself.

On Monday, as 100 people gathered to pay their respects in Trois-Rivières, a clearer picture emerged: he was a survivor, a friend, a teacher, a voracious reader and an activist who lived by a set of deeply held convictions.

But most of all he was a family man.

Not only to Dugas, Santiago, his sister and parents. But also to the expats who came to depend on him for advice on how to navigate life in Quebec.

Mendez, in particular, had built a deep connection to Malpica and his graduate studies on political violence in their homeland. When she heard the horrible news last week, Mendez went through her things and found Malpica’s 350-page thesis.

“He travelled to Peru and interviewed the families of people who’d been disappeared,” Mendez said. “It was a brilliant piece of work, full of empathy and love and passion. When I found the thesis, I sat down with a beer and read it all the way to the end.

“It was like spending the night with my old friend.”

***

They arranged a picture of Malpica on a wooden crucifix at the confluence of the St-Maurice and St-Lawrence Rivers.

Above the image of her partner, Dugas placed a postcard depicting El Cristo Morado, a painting of Christ draped in purple as he dies on the cross. This symbol of Peruvian Catholicism lives on in Montreal because of families who attend a procession in honour of the El Cristo Morado at an East-End church every October.

“The place would be bursting with people who didn’t normally go to church but for whom the day is sacred,” Dugas said. “We went every year. It was important to him to pass on that tradition to his son.”

She dug up an old photo of Malpica holding Santi inside the Nuestra Señora de Guaedaelupe church. It wasn’t that long ago but the boy looked so much younger then, sucking on his index and middle fingers as he peered from behind his father’s right shoulder.

At first, Dugas wondered if people would show up for Malpica at all. Though the community had rallied behind her after Malpica went missing, the couple was new to Trois-Rivières and didn’t have the same network as they did back in Montreal.

But while his time in the port city was short lived, Malpica had built relationships through his work with a local community group and as a popular new teacher at Collège Laflèche. It was his colleague at a local activist collective, Steven Roy Cullen, who assembled the crucifix and helped Dugas navigate the media storm that followed Malpica’s disappearance.

“I didn’t know him for that long and I regret that immensely,” he said. “Because his family and friends are such a wonderful reflection of who Eduardo was.”

Cullen acted as the event’s master of ceremonies Monday, installing a speaker and microphone for anyone who wanted to share a memory of their friend. Dugas didn’t say much except to thank everyone for coming and both Mendez and Incio were still too emotionally raw to say anything without bursting into tears.

“He couldn’t even swim, he was deadly afraid of water,” Dugas told friends, after stepping away from the microphone. “To be trapped under the ice, I can’t think of a worse fate for him.”

As dozens began pouring onto the shoreline, Dugas’ parents arrived with Santi. Mostly, the boy ran around with the other children and sat with the daycare workers’ who’d shown up for him that night. Towards the end, though, Santi walked up to Cullen and asked for the microphone.

“I… I don’t understand what happened to my papa,” he said. “Thank you for coming.”

***

Mourners left notes for Malpica during a vigil in Trois-Rivières Monday. PHOTO: Chris Curtis

Martín Incio left Mexico for Quebec nine years ago.

Like all immigrants, he said he experienced a form of extended grief in his new home. Though he loved how vibrant Montreal could be, a new language and culture were a lot to absorb. But he stuck to his French lessons and worked hard to make friends, falling for a Québécois woman less than a year into his new life.

When he started dating Marie-Claude, she told him about a Peruvian friend she was sure Incio would love. Years earlier, when Marie-Claude defended her thesis at the University of Ottawa, only one of her friends showed up to support her: Malpica.

“As much as you want to fit into your new country, you have to grieve the old one. Or at least, find a way to stay connected to some small part of it,” said Incio, who was also in Trois-Rivières for the vigil. “My mother’s side of the family comes from Peru and it was through Eduardo that I really gained a better understanding of my own roots.

“It feels funny to say that you’d cross a continent to find out where you came from but that’s how it happened. Over time, Eduardo became a good friend and then more like a brother. We played in the same soccer league, we would watch South American fútbol at Champs bar on St-Laurent Blvd. together or talk about the politics from back home.

“But we also embraced our new culture as well. I remember when the Canadiens made it to the Stanley Cup finals, we would watch every game and text each other throughout the match. I had never been interested in hockey before but it became another thing I could share with my brother.”

Mendez met Malpica in 2009 through her boyfriend at the time. He co-hosted a radio show with Malpica in college. And though the relationship with her boyfriend fizzled, she gained something profound in Malpica.

Together, they became members of Québec Solidaire — a leftist party that advocates for Quebec sovereignty and workers’ rights. By 2018, Mendez was in so deep that the party asked her to run in Montréal-Nord during the provincial election.

“When I told him I was considering it, he sat me down and wanted to know exactly why,” Mendez said. “He wanted to make sure I was doing it for the right reasons and he really put me through the ringer. It was only after I answered all his questions that he gave me his blessing.

“He was like that with everything, deeply inquisitive. If he wanted to go to the movies, he’d send this endless description of each possible choice; what the critics were saying, who the director was, what the cultural significance of the film was. That’s just how his mind worked.”

Though Mendez lost her bid for a seat in the National Assembly, she ran again in 2022 but this time it was in the southwest Montreal riding of Verdun — a neighbourhood Malpica introduced her to some years earlier.

“On the night I was elected, I had COVID-19 so I spent most of the evening on a Zoom call with Eduardo and our friends,” Mendez said. “Even under those circumstances, it was such a beautiful moment we got to share. He was so proud of me and I felt so lucky to have him in my corner.”

It was on the eve of Mendez’s swearing in ceremony, when she would officially become a Member of the National Assembly, that Malpica went missing. Mendez remembers getting to Trois-Rivières that weekend and scouring the city for any trace of her friend.

“It was hard to go back to Quebec City and focus on politics after that,” she said. “The session of the legislature started with his disappearance and now, as we prepare to close up for the summer, they just found Eduardo’s body. In a way, it’s like he was with me in spirit the whole time.

“At least, that’s how I choose to look at it.”

When police first examined Malpica’s body, it was in such an advanced state of decomposition that they couldn’t tell if it was male or female. After they finally identified him using dental records, their first instinct was to send out a press release claiming there were no signs of violence on Malpica’s body.

But the police don’t have the authority to make that ruling. For now, Malpica’s remains belong to the Quebec Coroner, who will conduct a detailed autopsy — including a toxicology report — before determining the cause of death. The coroner also has the authority to interview officers, witnesses and other folks who might help shed light on Malpica’s final hours.

Dugas says she’ll push to have the coroner’s report made public.

Like Malpica, Mendez’s family left Peru for Quebec when she was a teenager. Mendez says it was largely through Malpica that she started to embrace her dual identity as both Peruvian and Québécois.

“We celebrated Saint-Jean with the same joy that we celebrated (the national Peruvian holiday) because we loved our two countries,” Mendez said. “He said that when we love a place, we must get involved and fight for a better future for everyone.”

There was a time, early in my reporting, where I consciously avoided learning too much about Malpica. This is a job and when it starts bleeding into your personal life, you can’t do it for much longer.

But over the course of five months, after meeting Dugas, her parents, Santi, Mendez and Incio, I can’t stop thinking about him.

Not Malpica the victim but Malpica the dad, Malpica the writer of poetic text messages, Malpica the kid who gutted it out on the streets of Lima and made a new life for himself halfway around the world. Until his last day on this earth, Malpica would watch his son Santiago sleep at night to make sure he was okay.

Now that boy will grow up without a father.

“I think what’s saddest here is that Eduardo fought his whole life; for his family, for his friends and against injustice,” Dugas said. “That he died in such an unjust way may be the saddest part in all this.”

***

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.