The Devastating Attack on Safe Consumption Sites

As the opioid crisis worsens across Canada, the future of safe consumption sites is on the line — while toxic drugs continue to claim lives.

Content Warning: This article mentions substance use, overdoses, and abuse.

The last time Guy Felicella overdosed, he was unconscious for almost eight minutes.

He was at Insite, Vancouver’s safe consumption site, when nurse Sarah Gill found him unconscious. She immediately gave him a naloxone injection, put a breathing tube down his throat and an oxygen mask over his mouth as he lay on the ground, completely unresponsive. After he woke up, one of the first things he said was, “I don’t want to do this anymore.”

When someone goes into an opioid overdose, their veins collapse as their bloodstream overflows with the drugs. When too much of the drug enters the brain, even three minutes could cause permanent brain damage. They become drowsy and slip into a coma state as their nervous system completely shuts down.

Felicella overdosed six times in his life. Sometimes it was on the street, and luckily, people were around to help him. The other times were at a safe consumption site.

“I was very emotional after that last overdose, and I just knew then that I didn’t want to do this anymore. I didn’t want to die,” says Felicella. “But if that facility wasn’t there then I wouldn’t be alive on those days that I used there.”

In 2003, 10 years before his last overdose, Felicella was one of the first people to sign up at Insite. He remembers the place as welcoming, where nobody would judge him, and people were supportive unconditionally. Over those years, Felicella went to Insite over 4,800 times.

From 2017 to May 2024, safe consumption sites across Canada saw around 4.8 million visits from over 440,000 people. These sites have seen 58,444 overdoses — none of them have been fatal. Insite specifically has seen over 4 million visitors since it opened and has saved over 11,800 people from overdosing.

People go to safe consumption sites with their own substances to use in the presence of trained staff that can help in the case of an overdose. Many of them have medical clinics, drug testing to check for toxic supply, and harm reduction services like clean needle exchange.

Yet across the country, safe consumption sites are under attack.

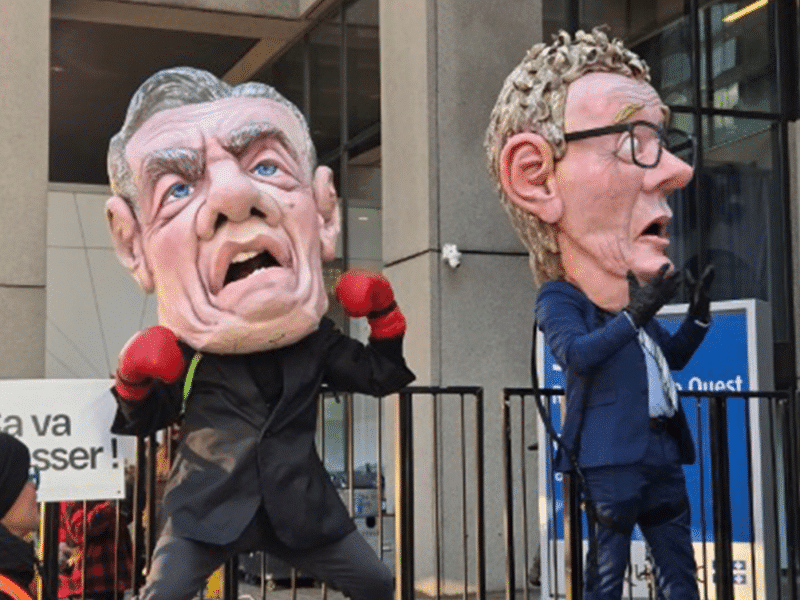

In Ontario, the Ford government is banning safe consumption and treatment services sites that are less than 200 metres from schools and child care centres. This would shut down 10 facilities across the province, five of which are in Toronto.

In Alberta, two safe consumption sites have shut down since 2020 due to provincial funding cuts. One of them, in Lethbridge, was the busiest safe consumption site in North America.

Pierre Poilievre has called safe consumption sites “drug dens” and promises that a future conservative government would shut them all down.

In Montreal, Maison Benoît Labre, a safe inhalation site in the Saint-Henri neighbourhood, has also come under scrutiny because of its proximity to an elementary school. Sud-Ouest borough mayor Benoit Dorais has requested the service be moved following allegations by neighbourhood parents of public indecency around the site.

None of this is new.

There is scientific evidence that harm reduction and safe consumption sites save lives and money. But as the opioid crisis gets more lethal every year due to the toxic supply, the easiest scapegoat is always harm reduction.

When there was a sharp increase in the supply of fentanyl in 2016, the opioid crisis in Canada severely worsened. Fentanyl is 50 to 100 times more potent than morphine and it’s cheap. Those two factors led to fentanyl being mixed into supply of other drugs like heroin and meth. Now it’s in practically everything.

At the same time, safe consumption sites are painted by politicians as an enabling force, while abstinence-based treatment is compared as a morally superior option. But abstinence isn’t an option for many people who use substances and have deep-rooted mental health issues.

***

Guy Felicella was addicted to heroin for over two decades when he had a striking conversation with his doctor Gabor Maté.

“You know, I don’t think your problem is the drugs, Guy,” Maté said to him. Felicella remembers this clearly.

He looked at his doctor and said, “Man, everyone says it’s the drugs.”

But Maté told him he was blown away by the sheer amount of drugs he was using — how his body was able to even consume such an amount. He said he never saw someone use drugs the way Felicella did. Then, Maté asked Felicella about his childhood.

“I just burst into tears. I couldn’t even speak,” says Felicella. “The funny thing about trauma is that you’ll deny it even exists because it’s too painful to look at.”

Felicella grew up in a volatile environment filled with violence and yelling. He would constantly hear negative things shouted at him over and over until eventually he internalized them. He felt like garbage about himself and was scared of other people and how they could treat him. The verbal abuse Felicella faced was, as he describes, the most crippling abuse he’s ever dealt with.

“I could always get over being punched in the face but the voices from the negative abuse… I was just trying to calm those voices from yelling at me all the time,” says Felicella.

At an age when he couldn’t control much in his life, he ran away to the streets of Vancouver and found what felt like the greatest thing in the world at the time: street drugs.

“You know, at 12 I wanted to end my life. And then you find drugs that save your life,” says Felicella. “I knew that what I’m doing is not the best for me but at the same time it allowed me to live just another day to figure it out and survive.”

Felicella continued using through his teenage years and into his adult life. But somewhere along the way he got involved with gangs, and the drugs got harder and faster. It was an intimidating environment for him, but at the same time he felt comforted there on the streets to see that other people were struggling too — that he wasn’t alone.

Between filtering through the foster care system and juvenile detention centres, Felicella also tried treatment many times but the recovery was always temporary. He could get off the drugs for a period of time but what never changed was how he felt about himself. So he would start using again.

It was only after he started going to Insite that he started the process of his long-term recovery.

Since 2016, there have been over 44,000 overdose deaths in Canada, 42,000 opioid-related hospitalizations and over 174,000 opioid-related emergency department visits. While British Columbia and Ontario see some of the highest rates of fatalities in Canada at over 2,500 overdose deaths in 2023, Quebec still saw 536 deaths in 2023, a 150 per cent increase from 2019.

Martin Pagé, the general director at Dopamine, a harm reduction centre in Montreal, says that safe consumption sites have to be creative because they are always under attack. Part of the issue, he says, is the lack of education that creates fear. The reality of these centres is quite the opposite.

When you walk into Dopamine’s drop-in centre, you find a bright, homey and nurturing environment. The centre hosts weekly breakfasts on Fridays, they provide medical services once a week, a needle exchange program, and folks have access to showers, laundry, and bathrooms. It’s a place of relief for the 30 to 60 people who come by every day. Their other location, a safe injection site, is open seven days a week from 8 p.m. to 1 a.m.

“We try to create a good and safe environment for everybody. Everybody is seen as an authentic human being,” says Pagé. “We are an efficient task force to try to diminish harm and to keep human beings alive.”

Another issue is pitting harm reduction methods against recovery treatment.

Access to safe consumption does not somehow diminish the utility of treatment facilities, and vice versa. And yet when the Ford government announced their plans to shut down safe consumption sites close to schools, they stated their intentions to expand treatment and recovery services, presenting them as a better alternative.

“It’s pointless to put us apart, put treatment apart and put harm reduction apart. It doesn’t make any sense to fight a crisis like that,” says Pagé.

While some people choose recovery services, they don’t work for everyone — particularly when they force an abstinence-only approach. In fact, some studies have shown that forced treatment and abstinence is worse than no recovery treatment at all.

A study done by Yale researchers showed that people with opioid use disorder (OUD) who are in abstinence-only treatment are more likely to die than those who receive no treatment at all. Abstinence can be deadly in these cases because the sharp shift from taking high doses of opioids to taking nothing at all can result in fatal relapses.

In Felicella’s case, he tried treatment and recovery programs many times but they were never effective long term. Often he would be in a program but when he got back out on the streets, he would go back to using pretty quickly because the root of his problems was never addressed.

“Somebody like myself that went into treatment for like 90 days, I didn’t even tap into the trauma that I’ve been going through all my life — none of it,” says Felicella. “All I did was stop using drugs, the drugs that I used as a coping mechanism for 31 years that now I was told to let go of.”

In Felicella’s experience, these facilities he went to over and over again weren’t equipped to deal with people struggling with serious PTSD and trauma. “Some do a better job at it, but this is also a lifelong process, and I relapsed so many times throughout my life,” says Felicella.

Isabelle Fortier, a harm reduction advocate, says that a safe consumption site could’ve saved her daughter Sarah-Jane Béliveau’s life. Sara-Jane overdosed in her university residence in Ottawa while using alone.

“She was hard on herself; I mean, why did she use alone in her room? She didn’t want anyone to know. I mean, she was ashamed. She didn’t want to disappoint anyone,” says Fortier.

Fostering understanding and education around substance use and mental health issues, Fortier says, is essential for people to build empathy around those who use. Her daughter had borderline personality disorder.

The line between someone who may have issues with addiction (specifically uncontrolled substances like opioids) and any other individual who goes to the bar with their friends after a difficult day at work is paper thin. Sitting in a bar in Montreal’s Quartier Latin, Fortier looks through a list of gins as she compares the bar to a safe consumption site. They’re both places to consume substances, the only difference is that the alcohol at the bar is regulated.

“I’ve been using a controlled substance in a beneficial way,” says Fortier, holding up her gin and tonic. “I’m not completely abstinent, because I do drink from time to time, but that doesn’t make me someone who has an addiction. But what if I didn’t have the support when she passed?”

The year after her daughter passed away, Fortier lost her home in a fire, then the COVID-19 pandemic hit, then a year after that she and her partner broke up. “When she passed, I could have gone to a little bit more harmful usage (of any substance), because I was dealing with some stuff, but I chose to do advocacy.”

Now Fortier wears a ton of hats: working with advocacy groups like Moms Stop the Harm to educate and raise awareness about the reality of addiction, working up in Nunavik, Quebec, to teach overdose prevention in Indigenous communities, and serving as a board member of Dopamine here in Montreal.

Harm reduction practices and safe consumption sites are helpful to people dealing with addictions because acceptance is baked into the nature of them, says Fortier. There is an understanding to see people as human beings first, and to know that people are using for a myriad of reasons that they have no control over, like the effects of trauma on their mental health.

“When we’re shaming people for their drug use, we’re actually shaming them for the reason why they use drugs… for something that they had no business going through — sexual abuse, verbal abuse, physical abuse, childhood suffering,” says Felicella. “Essentially, it’s not the drugs we point at, we point at the individual instead.”

***

Oona Krieg, Chief Operating Officer of Brave Technologies Cooperative which created the BC-based overdose prevention app Brave, explains that “a lot of folks will look at this community and see despair and suffering, and you know, having worked in this community for almost 20 years, I see the opposite. I see how people take care of each other. I see the little graces that end up happening. I see real harm reduction: people in the community treating each other like human beings.”

Krieg has already seen before what’s happening now with the fear around safe consumption sites. In 2016, when the crisis hit hard as there was a sharp increase in fentanyl in Canada, she said people just started to drop on the streets. Safe consumption sites were more important than ever. Yet, the Overdose Prevention Society and other harm reduction organizations were shut down (including during COVID) and were forced to change locations many times.

“So this is normal and not shocking, but also horrific. On the personal level, we all know that when a life source and a connection point shuts down for the people, immediately afterwards you’re going to see a big increase in fatalities, shortening of life, increase in violence in those places,” said Krieg.

Brave is an app that connects people who use drugs alone to a network of anonymous remote supervision. Essentially, it creates a virtual safe consumption site. It was built as a cooperative back in 2016 instead of as a nonprofit, because they didn’t want to be reliant on government funding.

“This is the playbook: no matter how much evidence you build that something is actually increasing the quality and the quantity of people’s lives, even if it’s serving them as it’s serving them, a new political wind will come in and just shut it down,” says Krieg.

Supervised consumption sites can’t be blamed for unaddressed societal issues like poverty and homelessness when their mandate is to simply save lives. People who are struggling with addiction need systemic support like access to affordable housing and mental health resources. Felicella says they also need an unconditional support system.

When Felicella got sober in 2013, he had to learn how to live again. He didn’t know how to make a resume and get a job or get credit from the bank. He said he needed someone to teach him how to live, to give him an opportunity. And for Felicella, it was his wife that taught him how to do that.

Today, Felicella is a harm reduction advocate and public speaker, sharing his experience in schools and conferences across Canada, raising awareness about addiction and the importance of harm reduction. He currently lives in Vancouver with his wife and three kids.

“Would I be where I am today without that individual, without my wife? I don’t think so. I think things might have turned out a lot different, and that just goes to show the support that some people are going to need to move forward,” says Felicella.

For many people, safe consumption sites are that support. And harm reduction spaces continue to be some of the most resilient ones, because they have had to adapt countless times. When they get shut down, they have pop-ups, they operate underground, they create mutual-aid systems, and time after time, they keep people safe.

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.