OPINION: The Town of Hampstead is in Crisis… and so is Local Journalism

Secrecy, self-dealing and a culture of entitlement thrive when there aren’t journalists asking hard questions to our elected officials.

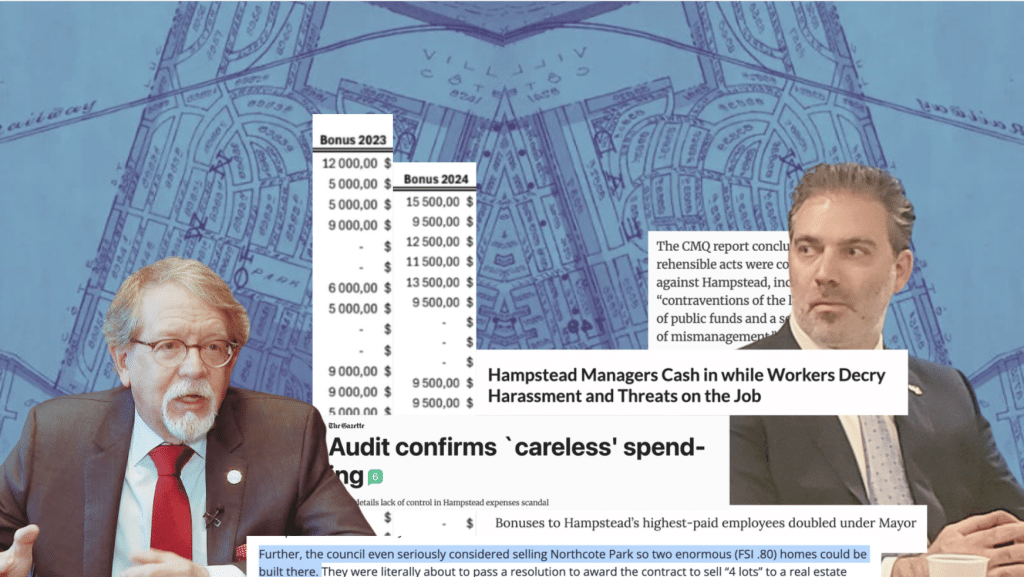

Shortly after he was elected mayor of Hampstead in 2021, Jeremy Levi and his council fired a whistleblower who reported the town to Quebec’s anti-corruption task force.

After that, the town’s elected officials saw fit to nearly double the executive bonuses of Hampstead’s highest-paid employees over the following three years. This is despite lawsuits and external investigations alleging a toxic workplace culture and out-of-control spending at the town.

By 2024, Hampstead’s Executive Director Richard Sun resigned following an investigation that found he spent upwards of $60,000 in taxpayer money on trips to Disney World, Las Vegas, and Barcelona, as well as a series of expenses that were personal in nature. An investigation by the Commission municipale du Québec (CMQ) ruled that Sun had used public funds to commit “reprehensible acts” while also finding “contreventions of the law, abuse of public funds and a serious case of management.”

Rather than dismiss Sun in the face of overwhelming evidence of wrongdoing, Levi’s council ordered a new investigation from the private security firm SIRCO and paid for it using public funds. The SIRCO investigation confirmed the CMQ’s findings.

Finally, last May, Hampstead’s council faced a town hall meeting packed with residents outraged over a proposal to have Northcote Park split into multiple properties and sold for luxury housing. It was only after this plan was publicized by former mayor Bill Steinberg that folks caught wind and pressured Levi’s council to back down. By that time, the council had already rubber-stamped a permit to subdivide the park into multiple lots and was about to hire a real estate firm to work on marketing the property.

This all happened with zero input from citizens.

The secrecy, the self-dealing and the culture of impunity at Hampstead’s town hall are all signs of a broken democracy. But perhaps the biggest scandal has been the absence of local journalists holding their elected officials to account.

Hampstead is hemmed into 1.7 square kilometres on the city’s west end, with just 7,000 residents calling the town home. Though its municipal government doesn’t control the town’s police force or transit system — the city of Montreal does — Hampstead punches far above its weight within anglo Quebec. Former mayor Steinberg has been at the forefront of Quebec’s language wars, and Levi has taken an inordinate amount of space in local media owing to his public and unwavering support for Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu’s genocidal campaign in Gaza.

But when it comes to covering the governance of Hampstead, The Montreal Gazette, The Suburban, CTV Montreal, CBC Montreal, Global News, CJAD and others have been playing catch-up. The reality of the modern newsroom is that with shrinking resources and high turnover, it’s much easier to cover one of Levi’s tweets calling for the ethnic cleansing of Gaza — which all of them have — than it is to take a deeper look into how the town uses taxpayer resources.

Only The Suburban, which covers Montreal’s West Island, regularly attends town hall meetings at Hampstead, but its reporting reads more like stenography than actual journalism. A reporter shows up, summarizes the meeting and takes everyone at their word with minimal fact-checking. Whether it’s because the journalist is overburdened or because Levi and Suburban publisher Beryl Wajsman share the same hardline views is unclear.

What is abundantly clear, however, is that this degree of political dysfunction thrives when people aren’t paying attention. Earlier this year, the Columbia Journalism Review published a study linking the disappearance of local newsrooms to a rise in corruption at the municipal level.

The study looked at 65 major American newspapers that closed between 1996 and 2018. It then looked at trends in federal corruption charges, comparing districts that lost a major newspaper to ones that didn’t. The results were staggering. On average, districts without a newspaper saw a 6.9 per cent increase in corruption charges, a 6.8 per cent increase in the number of indicted defendants and a 7.4 per cent increase in corruption cases filed.

Canada is not immune to this. In the past 17 years, some 571 local newspapers have shut down across the country. Three-quarters of those were community papers that published less than five issues a week, often acting as the only safeguard against municipal corruption.

Even in big cities with big news outlets, the trends are alarming. Two years ago, in Toronto, the auditor general fielded 1,032 complaints for wrongdoing or misuse of municipal funds. That’s far and away the most it had ever received. The following year, that record was broken again.

And while it was the dogged investigative journalism of reporters like Linda Gyulai at The Gazette and La Presse’s André Noël that led to Quebec’s long-awaited reckoning on municipal corruption, the Charbonneau Commission’s work ended 10 years ago. The decade since has seen layoffs in newsrooms across the city and the re-emergence of major scandals in Montreal and municipalities across Quebec.

Which brings us back to Montreal’s municipal elections.

With a huge swath of electors still undecided and little to indicate that voter turnout will surge beyond the usual low 30s, it’s clear that the press hasn’t done enough to make local politics interesting to voters.

The frontrunner, Ensemble Montréal leader Soraya Martinez Ferrada, inherited a party that traces its roots to the corruption-plagued Union Montréal party. Union was dissolved in 2013 after three of its members were arrested on corruption charges, and one, former mayor Michael Applebaum, actually served time for breach of trust. Most of what was left of Union was absorbed by Équipe Denis Coderre, who later changed the party’s name to Ensemble Montréal.

Her challenger, Luc Rabouin, is the leader of Projet Montréal, a party that saw rent and homelessness in Montreal nearly double during its eight years at the helm. Of course, homelessness and the cost of rent are driven by factors far outside the city’s purview, but Rabouin will still have to own Montreal’s out-of-control housing market because that’s just how politics work.

How did we get here?

Back in 2017, when I worked at The Montreal Gazette, we created something called the engagement team. Our job was to figure out the kind of content — notice I’m not using the word “news” — that would make our readers spend more time on the paper’s Facebook and Instagram. Sometimes, that coincided with our journalism mission, but mostly we were feeding them the journalistic equivalent of crack cocaine. We brought more people in, but the paper kept losing money.

Even now, on The Rover’s Instagram, we’re far more likely to get engagement on a post about Soraya Martinez Ferrada briefly living in Longueuil — a mini scandal that doesn’t have much bearing on the election — than we are if we post a detailed breakdown of housing policy. We have to be mindful of that because it’s easy to be seduced by the dopamine rush of likes and shares. I’ve certainly been guilty of it.

We can talk about government bailouts to legacy media and the necessity for publicly-funded independent news, but ultimately, it has to start with good journalism. People need to see it before they can believe in it.

At The Rover, we realized early on that going after web traffic is a mug’s game. What good is it if 250,000 people read your article if that article is just clickbait? They can get that anywhere. But most legacy media are still chasing those clicks because that’s the business model. Drive engagement, sell ads and hope the windfall funds boots-on-the-ground journalism. It hasn’t changed despite decades of evidence that it’s broken.

The real challenge, for all of us, is to make the kind of news that doesn’t aim to draw in tens of thousands of casual observers, but a smaller, more politically engaged crowd that wants to read groundbreaking journalism. Sometimes that means going days without publishing (a nightmare in an ad-driven environment). In other words, it is going to require a massive overhaul of the way we produce and fund journalism. I don’t see legacy media pushing for that.

If we look back at Hampstead, the voters don’t stand much of a chance.

On the one hand, you have Levi, who oversaw a scandal-plagued administration, versus Steinberg, who served four terms as mayor, and councilman Jack Edery, who signed off on virtually all of Levi’s agenda.

To some degree, we did this. Journalists like to talk a big game about how we’re essential to democracy without realizing that we also play a corrupting role in the process.

Thanks for doing this work. Also, thanks for not deleting the scammy comments at the bottom of the article as they provide significant humour necessary to feel less incpndecdnt with rage towards slimy politicians after reading about their goings on. Cheers.