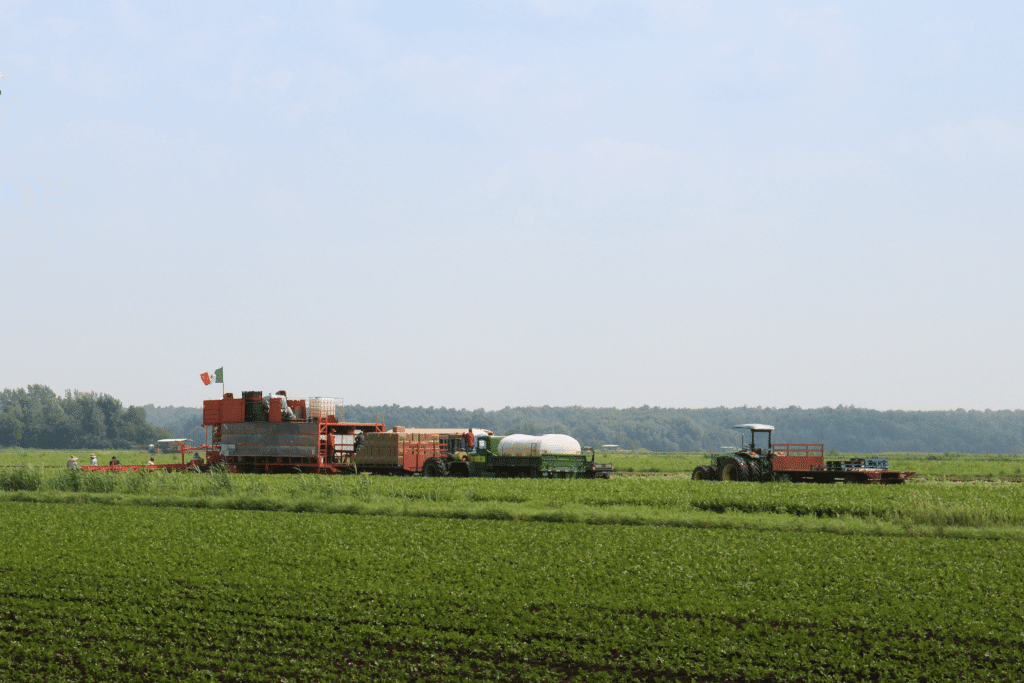

“Without Our Labour, Who Would Work?”

Temporary foreign workers leave their families behind to fill essential jobs that keep farms in the country running. Experts argue Canada has unfairly benefited from their skills and experience without assuming any responsibility for them.

PHOTO: Darwin Rodriguez

When Jesús Reyes arrived at the farm in Saint-Pie, Quebec, it wasn’t what he expected.

“I imagined a place with pigs, sheep, goats, cows, land, and machinery,” explains Reyes, who came to work on a poultry farm from Irapuato, a city in Guanajuato, a state in central México. He arrived in Canada six months ago for his first season as a temporary foreign worker.

Jesús worked with his grandfather in México for a decade. Under his guidance, he learned all the farm chores, from feeding the animals to managing the crops. With that knowledge and experience, he came to work at Ferme Avicole Francis Brodeur, a fourth-generation farm in the Montérégie region of southwest Québec.

“I had never seen a farm like this in my country. Everything is automated, which is new to me. I’ve learned many things I didn’t know,” says Reyes.

His work day starts at 7:00 a.m. every morning, beginning by taking the eggs out, cleaning them, and classifying them by size. Inside the warehouses storing the chickens are long corridors with tall metallic structures on the side where the hens are separated into cages. The eggs are transported along the edge of each hen house on a conveyor belt after the hens lay them. At the end of the belt, a machine places 30 eggs per box while Reyes removes the broken ones, the double yolks, and the ones that need to be cleaned. The farm produces an average of 60,000 eggs per day.

Like many temporary foreign workers, Reyes leaves his country for months at time — in his case for one year — to work a minimum-wage job in Canada.

His wife and three children stayed in Guanajuato.

“Everything I do is for them. You have to suffer a little bit for them to be well,” says Reyes, his voice cracking. “I had never been far from them.” He talks to them every afternoon after work. Recent visa changes for Mexican nationals make the distance even greater, as the families of temporary foreign workers can’t come to visit them while they work.

Being a temporary foreign worker sometimes means being isolated.

When Reyes is not working or talking to his family, he watches videos on social media in his room. Some weekends, he rides his bike to the river and watches people fishing in their boats.

He lives near Saint-Pie in a house with three workers from Guanajuato, but they don’t go out often. The stores are far away from their house.

“Every Thursday, our boss picks us up to buy groceries for the week because we get paid. Every Thursday is my social day,” says Reyes.

Jesús, like many other temporary foreign workers, depends on his employer to have access to fundamental rights like accommodation, health care, and even transportation.

“We cannot say as a society that they (workers) have to learn the language because they decided to come here. The same company that hires them chooses the nationality of the workers they want to hire,” says Véronique Tessier, assistant director for the Réseau d’Aide aux Travailleuses et Travailleurs Migrants Agricoles du Québec (RATTMAQ). “So we have to ask ourselves why they bring people who are not going to be able to integrate here.”

One of the criticisms Tessier levies against the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) is the power each employer yields through the use of closed work permits. The employer is responsible for integrating their workers into society.

Isabel Ramos sells multiple products and crafts from México at La Variété / La Variedad. PHOTO: Darwin Rodriguez

A couple of years ago, Isabel Ramos — a woman from Guanajuato and the owner of a store called La Variété / La Variedad — decided to host parties for the temporary foreign workers in a community hall in Saint-Rémi, a town 30 minutes south of Montréal, to contribute to their integration.

“I saw all these workers alone and thought, ‘What can I do to bring these people together?’ So I decided to organize parties.” She printed flyers and posted them on the doors of the supermarkets the workers frequented so they could see them. “It was nice to get them out of their routine, out of their loneliness.”

During the COVID-19 pandemic, the parties stopped, but her business continues to be a meeting point for many temporary workers. The store is open on Wednesday, Thursday, and Sunday, the days when temporary workers receive their pay and go to the store to buy groceries and send money to their families. Sometimes they ask Ramos to translate something they need to tell their bosses in French.

“More than a business, this is a brotherhood that we created among all of us.”

RATTMAQ also hosts parties in different cities and towns around Québec to integrate temporary foreign workers and to acknowledge their labour.

Even though many temporary foreign workers like Reyes have had good experiences with their bosses, some employers have taken advantage of the power they have over their employees through closed work permits.

For Tessier, this isolation and the difficulties of integration create a ‘workers ghetto.’

“It is logical that if you want to have a docile workforce, that is always willing to work and that has no activity other than work, then you have to bring men who are fathers, who won’t want to stay to apply for residency or stay illegally because they have family in another country.”

The ‘docile workforce’ is also linked to the nationality of the foreign workers because employers can demand workers of a specific nationality.

“Do you know why they prefer Latin American workers? Well, because in their mind and in the industry there’s the belief that Latin American workers are well adapted to physical work, that they are ‘made for it,’” explains Tessier.

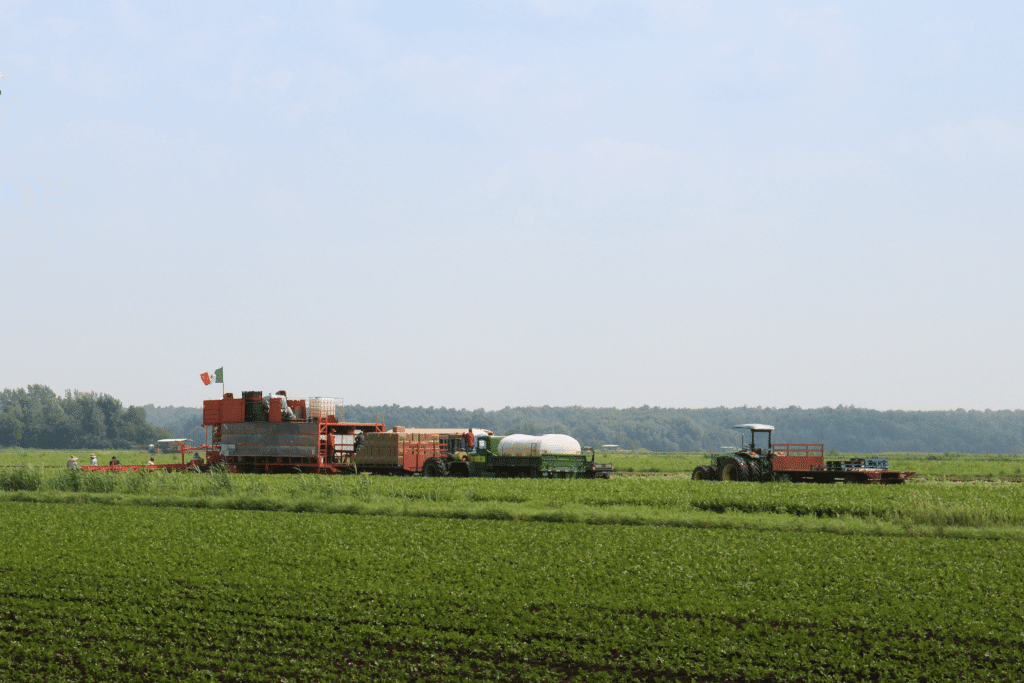

In the past four years, the majority of temporary foreign workers came to Canada from México, Guatemala, and Jamaica.

A Mexican flag is raised on the tractor used by temporary foreign workers in a soybean crop in Sainte-Clotilde, Québec. PHOTO: Darwin Rodriguez

***

On May 1, Canada’s plan to shrink the number of temporary foreign workers in the country by 2027 came into effect. It cut the number of low-wage foreign workers that companies can hire in most sectors from 30 per cent to 20 per cent of their workforce.

Canada’s Employment and Workforce Development Minister Randy Boissonnault said the Temporary Foreign Worker Program (TFWP) is a “last resort” and businesses should exhaust every option to prioritize workers here in Canada before applying for temporary foreign workers.

For several years, agricultural businesses in Canada have relied on foreign labour to make up for labour shortages. The number of people willing to work in agriculture in Canada has shrunk due to an aging workforce and negative perceptions about working in the sector. One of the reasons Canadians are not interested is the physical toll of the job.

Without temporary foreign workers, many farms would have been forced to close, leading to Canadian job losses.

According to Statistics Canada, nearly one in four agriculture employees (23.2 per cent) in 2022 were temporary foreign workers.

Canada benefits from the labour of temporary migrant workers without assuming any responsibility for them, because employees have access to their fundamental rights through their employer.

In one case reported by The Rover, dozens of immigrants from Latin America face threats of deportation, illegal working conditions and unpaid wages after being recruited by an agency under false pretenses of legal work, fair wages and an opportunity to become permanent residents.

Advocates for the rights of temporary foreign workers have shown how work permits tied to one employer undermine the workers’ ability to organize or demand better conditions.

Ildefonso Flores, a temporary worker from Tlaxcala, the capital of the eponymous state in east-central México, created a YouTube channel to expose the complaints of some of his colleagues who report unsafe working conditions or a bad housing state.

“I decided to create the channel to raise awareness among the people here [in México], to help our fellow countrymen. I speak for my colleagues who haven’t had the courage or have not been able to raise their voices out of fear because they are exploited and they have to continue working,” explains Flores, who is the son of temporary workers.

In México, he is an English teacher for primary school and has a sound equipment rental business. He says he came to Canada because his salary is low and there is a lack of opportunities in his country.

“People really don’t know what a sacrifice it is and how hard it is to work in the fields in Canada because of the climate, the hard work, and sometimes the racism among coworkers,” says Flores. “Somebody told me, ‘You are from México, you put up with these (high) temperatures.’ We are not made for that; we are here because there are no opportunities.”

In his eyes, there is an ideal among immigrants of how it is to be a temporary worker in Canada, and it is created, in part, by the same workers.

“My countrymen return and don’t tell the reality they live and how they are treated, because they are ashamed. They say, ‘I did well, I earned so much money by doing nothing.’”

He says that Latin Americans have been taught to put up with hardships no matter what. One season, he had to work on a summer day when the temperature was 38°C. Farm workers have a high risk of heat-related illnesses as climate change drives average temperatures higher.

“All my respect to all of us temporary workers. This is one of the hardest jobs, because you also risk your life. We need to work so we don’t have to go back to Canada. We need to invest our money so we can be with our family,” says Flores.

Ildefonso Flores. PHOTO: Courtesy

On Tuesday, Minister Boissonault said in a meeting with representatives from the food and beverage, transportation, and agriculture industries that he is considering refusing temporary foreign worker applications under the program’s low-wage stream to end the abuse and misuse of the TFWP.

“The biggest issue is that nobody seems to have thought that when foreign workers come, they’re going to want things like housing, doctors, and schools. The failure is the politicians who didn’t lay the groundwork to ease foreign workers into the economy. When all of these foreign workers show up, the problem is not them. It’s the politicians,” says Moshe Lander, a senior lecturer in economics at Concordia University.

Immigration Minister Marc Miller said last year that he was willing to examine ways to ease restrictions on some temporary foreign workers after Tomoya Obokata, the UN special rapporteur on contemporary forms of slavery, expressed his concerns in a report following his visit to Canada. Obokata stated that he was “particularly concerned that this workforce is disproportionately racialized, attesting to deep-rooted racism and xenophobia entrenched in Canada’s immigration system.”

In fact, a class-action lawsuit highlights the “racist and discriminatory” origins of so-called tied employment in these schemes. The suit alleges that Canada’s migrant worker programs violate the country’s Constitution.

The Association pour les Droits des Travailleuse·rs de Maison et de Ferme (DTMF) has a similar argument. The organization launched the constitutional class action lawsuit End Migrant Worker Unfreedom, which aims to end employer-specific work permits and obtain compensation for all temporary foreign workers who have been barred from changing employers in Canada since 1982.

According to them, the system contributes to the violation of workers’ rights to life, liberty, security, freedom from cruel treatment, and non-discrimination based on the country of origin.

The DTMF is waiting for the decision on the authorization hearing that occurred on June 12 to know if the case can proceed as a class action. If the authorization is granted, the case will proceed to trial, and they’d present the court arguments and evidence about why closed work permits are fundamentally incompatible with numerous rights protected by the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms.

“We are not asking for a monument or a statue, but acknowledgment among people that there is racism, that the workers’ rights must be recognized, that we must be paid better, and that without our labour, who would work?” says Flores.

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.