Opinion: Abisay Cruz and the Politics of Abandonment

Who polices the police?

In October of last year, SPVM director Fady Dagher had a message for the parents of Montreal. “Please,” he said, “when we come to meet with you, don’t close your door.”

The police, he explained, were reaching out to parents in the hopes of helping youth in trouble with the law.

“It takes a village to raise a child,” he said.

We were reminded of Dagher’s plea last month when we learned two men in separate incidents have been killed while in police custody: the first in the Centre-Sud, the second in Saint-Michel.

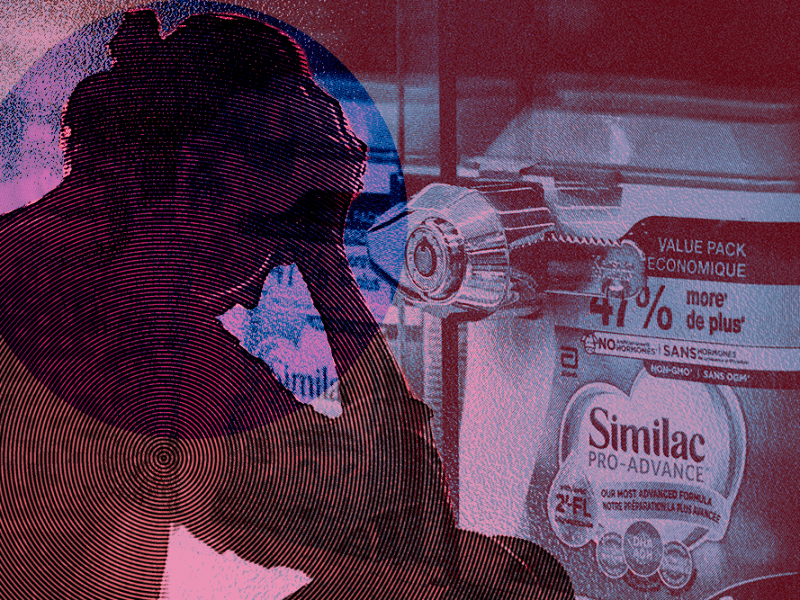

In the second case, a video circulating on social media shows three police officers crammed onto the back balcony of a second-floor apartment. A Latinx man, Abisay Cruz, is lying face-down on the ground with handcuffs around his wrists, though no one is alleging he committed a crime. An officer’s knee is pressed into Cruz’s upper back or neck, though he is very clearly struggling to breathe due to the force. Another officer pounds on the back door of the apartment, ordering the occupants – Abisay’s family – to open the door (he didn’t say “please”) and kicking the door with his boot, again and again, until it finally gives way and two officers march inside.

As the police marched in, Abisay was taking his final breaths under the knee of their partner outside. He was pronounced dead at a nearby hospital later that morning, leaving his family—including his 9-year-old son, Enzo— in the throes of grief and terror.

There is a logic to the closed door. Who would open the door to the police when they see and hear excessive force being used against a loved one struggling to breathe outside? Why is there such distrust of the police in racialized communities and neighbourhoods like Saint-Michel? What, in the context of this earned distrust, is the lecturing of a police director supposed to accomplish, aside from blaming communities for the actions they use to survive?

Support Independent Journalism.

This distrust of the police did not begin under Dagher’s watch. After the police killing of Anthony Griffin in 1987, a common sign at protests asked, “Who polices the police?” In the next four years, the Montreal police went on to kill three more Black men and one Latino man. As Black activist Orin Bristol told the CBC in 1991: “There is terror gripping the community, and we’ve got to investigate why these people are afraid of the people policing them. Who is policing the police?”

The question has been asked repeatedly over the years, and it was raised once again during the protests that followed the killing of Abisay Cruz. The question rejects the most obvious answer today: that the Bureau des enquêtes indépendantes, created in 2016, “polices the police.” In its nine years of operation, there have been 60 deaths at the hands of the police in Quebec, and none of them has resulted in charges against a police officer.

The question implicates more than the police. It emerges from the widespread feeling that people like Abisay and neighbourhoods like Saint-Michel are ignored by those in power and forced to endure racialized poverty, underfunded social services and institutions, and a police force that is allowed to run rampant. Some will remember when, in 2021, Mayor Valérie Plante and Premier François Legault visited the neighbourhood, it was to honour the death of a white teenager – an honour he deserved, but not only he deserved.

The last time Mayor Plante spoke out against police racism or violence was June 2020, when a police force she didn’t oversee killed George Floyd. Voicing her opposition to “systemic violence, racism, and discrimination,” Plante announced that “the city is engaged in an important project of combatting racial and social profiling.” Four years later, when a major report on racial profiling within the SPVM showed the problem had gotten worse since her 2020 statement, Plante had nothing to say and no further actions to announce.

Who polices the police? It is a question neither Fady Dagher nor our political leaders seem to be concerned with, but their silence suggests an answer: no one.

It’s worth returning to Dagher’s plea last October, which invoked the first part of a well- known African proverb, “It takes a village to raise a child.” It notably omitted the second part of the proverb, which suggests the potential consequences of the racialized abandonment in Montreal today: “The child who is not embraced by the village will burn it down to feel its warmth.”

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.