Mohawk Dispensary Owner Fights Illegal Dumping Allegations

Barry Bonspille says he’s not dumping contaminated soil into the lake but reclaiming family land lost to floods and erosion.

Like all of Kanesatake’s dispensaries, Golden Star Cannabis and Gaming operates in a legal grey area.

The store sells cannabis and alcohol on its premises while running four slot machines — all perfectly legal products and services in Quebec. But it does so without paying tax or submitting to regulation from any outside government.

Still, the store hangs a copy of the Cannabis Act above its cash register, and staff ask each potential customer for identification, turning aside anyone under 18. The store’s owner, Barry Bonspille, says he’s repeatedly asked the Mohawk Council of Kanesatake to take an active role in regulating the industry, but they never followed through.

Because none of the Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) territory’s dozens of cannabis shops are regulated, they can’t rely on police protection. Police sources say there have been 18 arsons and attempted arsons in Kanesatake in the past year alone, with most targeting cannabis retailers and none resulting in arrests or convictions.

Arsonists have tried to burn down Golden Star twice since last summer. Sources inside the industry say these acts of arson are used to settle business disputes, eliminate competition or to let a budding entrepreneur know they’re not welcome on the territory.

Support The Rover: we get results!

The score settling has escalated violently on several occasions, as was the case when two men exchanged gunfire outside the Sweetgrass Lodge last November. Four years ago, Montreal gang leader Arsène Mompoint was shot to death during a July 1 party at the Green Room dispensary and casino. No arrests were made in either shooting.

But of all the controversies surrounding Kanesatake’s dispensaries, none have been more contentious than the allegations that some owners have been part of an illegal dumping scheme that’s seen thousands of tonnes of contaminated soil into the Lake of Two Mountains. Most have done this so they could expand their lakefront property and business.

Bonspille is among 17 defendants targeted by a provincial injunction to halt dumping on the shoreline last fall.

In theory, the dumping was supposed to stop while Crown prosecutors made the case that this dumping presented a “grave threat” to aquatic life and drinking water in the region. But over the past month, sources in Kanesatake have provided The Rover with photo and video evidence of earth and gravel being dumped near the shoreline on Bonspille’s property.

Bonspille, a former high school principal who holds a Master’s degree from Queen’s University, is the first dispensary owner to agree to be interviewed regarding these allegations. While some have threatened our reporters with violence and warned us to back off our investigation, Bonspille was thoughtful and surprisingly forthcoming.

In an hours-long conversation, the 62-year-old presented The Rover with lab test results and truck manifests showing that rather than contaminated soil, he’s been importing boulders, gravel and clean fill to “reclaim” property that was lost to decades of flooding and erosion.

This is his story.

***

The property where Golden Star was erected two years ago was once a beach where Bonspille’s family rented out boats to tourists.

Bonspille grew up on a corner of that land in a house without indoor plumbing and just one faucet for the whole family.

This wasn’t some bygone era in a faraway community. It was 1974 in Mohawk territory, just a 45-minute drive northwest of Montreal. On a pasture south of Route 344, Bonspille’s family raised cows, pigs and set aside its beachfront property to rent to campers.

“I thought indoor plumbing was for rich people,” Bonspille said. “No one gave it a second thought because that’s how everyone lived. My cousins, our neighbours, everyone we knew lived a simple life.”

Once a massive territory that stretched for nearly 700 square kilometres, centuries of land theft reduced Kanesatake’s territory by 98.5 per cent, leaving the Mohawks with a sliver of red clay where the Ottawa River meets the Lake of Two Mountains.

Elders in Kanesatake say the lake began to swell in the 1960s, when the Carillon dam was built some 30 kilometres upriver from the community. Over time, Bonspille says the water swallowed over 100 feet of his family’s property, destroying their beach business, uprooting trees, and ultimately making the farm worthless. Some seasons, the opposite problem — drought — made the water recede by hundreds of feet.

He says he has documentary evidence to prove this in court.

“My grandfather, he wrote to the Minister of Indian Affairs, he even wrote to the queen. He wanted the government to fulfill its most basic duty and protect our land against flooding,” Bonspille said. “But they didn’t care about poor Indian farmers in Quebec.”

With Bonspille’s grandfather getting too old to manage a dairy farm and debt mounting, the family ran out of options. None of Bonspille’s uncles or his dad could take over since they were all working outside the community. And the children weren’t out of school yet. So the business went under, and the Bonspilles had to sell every piece of equipment and livestock they owned to stave off financial ruin.

“My whole life, I just wanted to be a farmer like my tóta (grandfather),” Bonspille said. “It was devastating when we lost that farm.”

With the small plot of land divided between the descendants of Bonspille’s grandfather and with so much lost to erosion, it is unlikely any Mohawk — no matter how industrious — could make a living as a farmer.

“The Dagenais family (in the heart of Kanesatake’s commons) probably own more land than all of us put together,” Bonspille said. “They have scale, they have access to grants we’re not eligible for, and they’re doing all of this on land that used to be ours. Trying to compete with that feels like a futile act.”

While Bonspille says he’s been importing boulders and fill to reclaim family land lost to flooding, the Quebec government argues otherwise. Crown prosecutors claim Bonspille’s land is one of 17 Mohawk properties being used as a massive illegal dump site.

Specifically, the Crown has presented Quebec’s courts with evidence that these properties accepted contaminated soil from outside trucking companies looking for a cheap way to dispose of construction refuse. By allowing dumping directly into a body of water where fish spawn or within five meters of the shoreline, land owners could be liable for up to $1 million in fines for violating Quebec’s environmental protection laws.

“Almost all of our land has been stolen by settlers, and what little is left is being used as a dump,” said Greg*, a Mohawk who lives near Golden Star. “We’re fed up with seeing all these outsiders contaminating our land and water. Enough is enough.”

Police have not received complaints about the dumping in the past month, according to the Sûreté du Québec. But sources inside the community say they wouldn’t trust the police to do anything about it even if someone did call 911 on their neighbours. Evidence presented in court last fall suggests the cops had been aware of illegal dumping for at least a year but did not intervene until The Rover published a series of articles outlining the scale of the problem.

The Mohawk band council, meanwhile, has had a tumultuous decade marked by infighting and an investigation into the SQ’s financial crimes unit involving employees of the council. With no local police force, they lack the power to enforce the provincial, federal and community laws being broken by the people who dump on their land.

Bonspille says he understands why some community members are suspicious of the dumping due to recent contamination in other parts of the territory.

And at the height of the dumping, last summer, hundreds of trucks unloaded on the reserve every day — causing massive dust clouds and a level of traffic way beyond what the territory was meant to handle. Bonspille says that while he can’t speak for other property owners, he never participated in illegal dumping.

“That’s why I ensured that the material brought to my property was above board,” said Bonspille. “Cause I know the issue of dumping has left a bitter taste in this community’s mouth.”

Beyond the erosion that ate away at his family farm, Bonspille worries about two “once-in-a-century” floods that hit the reserve in 2017 and 2019. He also contends that with the risk of more floods related to climate change, his reclamation project will effectively protect his family’s land from being overtaken by future natural disasters.

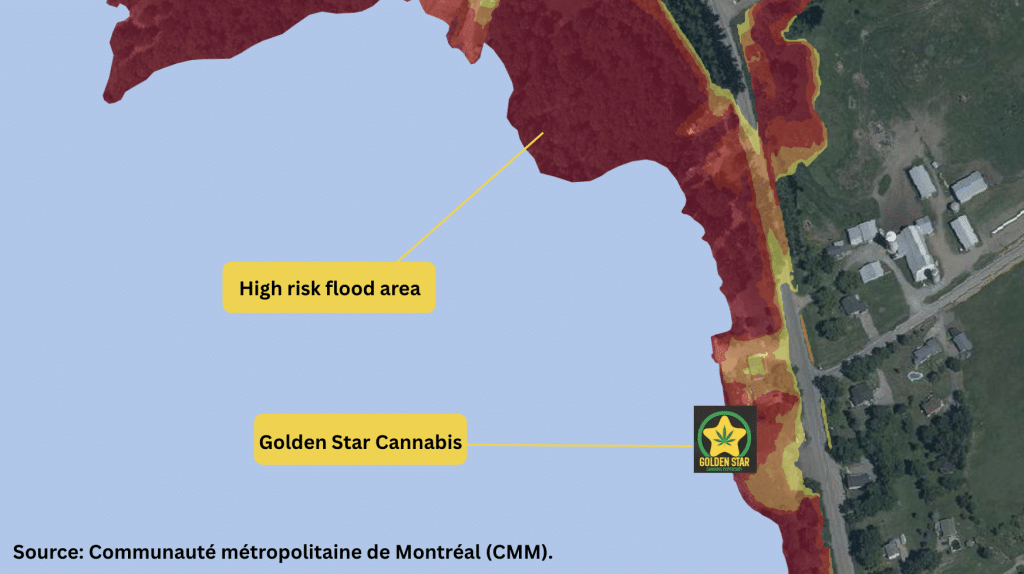

Bonspille’s family property is on a site considered at “very high risk” of flooding, according to a map of floodplains redrawn after the flooding in 2019. That designation means that, each year, the family property is at a 5 per cent risk of being submerged.

One environmental expert is skeptical of Bonspille’s logic.

“Hardening the shoreline against floods is often used, by property owners, as an excuse to expand their waterfront property,” said Daniel Green, an environmentalist and former deputy leader of the Green Party. “It’s true the land is on the flood plain, and the risk of flooding is greater now than it was decades ago. But to just dump gravel directly into fish habitats, that’s not the solution.”

Green has been following the court case involving the 17 waterfront properties in Kanesatake and says it looks like the government’s case “is going nowhere fast.”

“There’s been evidence of contamination presented in court, soil and water samples that show hydrocarbons and heavy metals well beyond provincial norms,” Green said. “But most of the defendants aren’t hardened criminals. They’re elderly people, they’re people living in poverty who may have accepted soil on their land without knowing where it came from.

“If the goal is justice, the Crown should have pursued the people doing the dumping, not the ones receiving it.”

Bonspille says his lawyers asked for evidence that he dumped contaminated soil in the water but was merely provided with a photo of “asphalt” being dumped on his property. Bonspille says the photo in question depicts crushed stone and that he was never given lab test results or any concrete proof of contamination.

Late last year, The Rover learned that the Laval-based excavation company Nexus was under criminal investigation for its alleged role in the dumping scheme. We followed Nexus trucks from construction sites in Laval and Montreal to a large waterfront property in Kanesatake.

The soil collected by Nexus trucks contained slabs of asphalt, making it contaminated by hydrocarbons. But instead of disposing of it in a provincially-sanctioned dump site — as is required by law — Nexus dumped the soil near and directly into the Lake of Two Mountains. They did this because it saved them a fortune, spending a few hundred dollars to offload onto Mohawk land instead of paying double or triple that price at a legal dump site.

But Bonspille says he doesn’t do business with Nexus and swears that his shoreline reclamation project isn’t harming fish habitats.

“I grew up on this land. I swam and fished here my whole life, the last thing I want to do is pollute it,” Bonspille said. “I’m telling you, my reclamation project is focused on land and sand that used to be covered in trees. This wasn’t part of the water.”

Still, the business owner makes no bones about selling cannabis, alcohol and games of chance.

“These are all legal products, Quebec is in the gambling business, the cannabis business and Quebec profits immensely from the sale of alcohol,” Bonspille said. “So why do we Mohawks — who are a sovereign people — not have our own right to free enterprise?”

Asked whether his business is backed by money from organized crime, Bonspille was unequivocal.

“These are investors I’ve known since I was a teenager,” Bonspille said. “I essentially have a mortgage on my business. It’s probably over half a million dollars in the building, the reclamation, the advertising and the product.

“I did my vetting, these are people I know. We’ve worked out favourable terms. It’s a business deal. I would have preferred economic development through council and Canada. But the way it’s structured is limited, they hand pick these overly safe projects that always fail.”

The influx of cannabis cash onto the territory has fueled legitimate businesses like gas stations, restaurants and convenience stores in a community where it’s notoriously difficult to get a bank loan or business development grant. And for all of the gang-related businesses, there are far more small dispensaries run by Mohawk families looking to build intergenerational wealth.

But the drug trade has also brought fear and chaos onto the territory.

There have been at least two high-profile incidents where outsiders drinking alcohol at a dispensary crashed their car on the territory. In one collision — which occurred last year — a man from a neighbouring community barrelled over a ditch along Route 344 and smashed into a steel pole.

In another, a Mohawk mom and her daughter were struck by a pickup truck that had just pulled out of a lakeside bar-casino-dispensary. The driver and victims sustained minor injuries, but after he was taken away in an ambulance, locals beat his truck with baseball bats and spray-painted the words “enough is enough” on it.

Ultimately, Bonspille says the emergence of a cannabis economy comes down to two factors: land and money. The Kanesatake Mohawks’ right to their traditional territory — a 689 square-kilometre swath of land that encompasses farming communities like Mirabel, St-Joseph-de-Lac and Ste-Placide but also suburbs like Deux Montagnes and St-Eustache — was recognized by the king of France over 300 years ago.

Today, negotiations to compensate the Mohawks for that theft have dragged on for decades. And because what land they have left is held in trust by the federal crown, Mohawks can’t use it as collateral for bank loans and other tools that might give them a fighting chance in this capitalist system.

Instead, roughly half of the 2,700 members of the Kanesatake band are stuck living outside the territory with little prospect of ever coming back home.

“We didn’t put ourselves in this situation, we’re out here trying to make solutions for ourselves,” Bonspille said. “If the federal government, if our band council lived up to their fiduciary obligations, we wouldn’t be here.”

Did you like this article? Share it with a friend!

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.