Opinion: A Cellphone Ban Without a Plan

Quebec’s plan to ban cell phones during school hours without educating students to use them outside school is like putting a band-aid on a broken arm. Here’s why:

Quebec’s plan to ban cell phones during school hours without educating students to use them outside school is like putting a band-aid on a broken arm. Here’s why:

The internet didn’t exist when I was 14 years old — this was the late 1980s.

Everything I knew, I learned from my teachers, my parents, and Seventeen magazine. Of course, there were conspiracy theories about JFK, UFOs, and Bigfoot going around, but they were hard to find: you’d have to sit next to your drunk uncle at Thanksgiving to learn about them.

Today, 14 years old is the peak age for believing in conspiracy theories, according to a study published in the British Journal of Developmental Psychology in 2021, one of the first to measure conspiracy theorizing in children. The study found that these beliefs carry on into early adulthood.

Here are a few statements kids were asked to rate their agreement with:

- Governments have deliberately spread diseases in certain groups of people.

- Secret groups control people’s minds without them knowing.

- Secret societies control politicians and other leaders.

When kids believe ideas like these, they become victims of what’s now considered to be the most severe and likely global threat: disinformation — fake news.

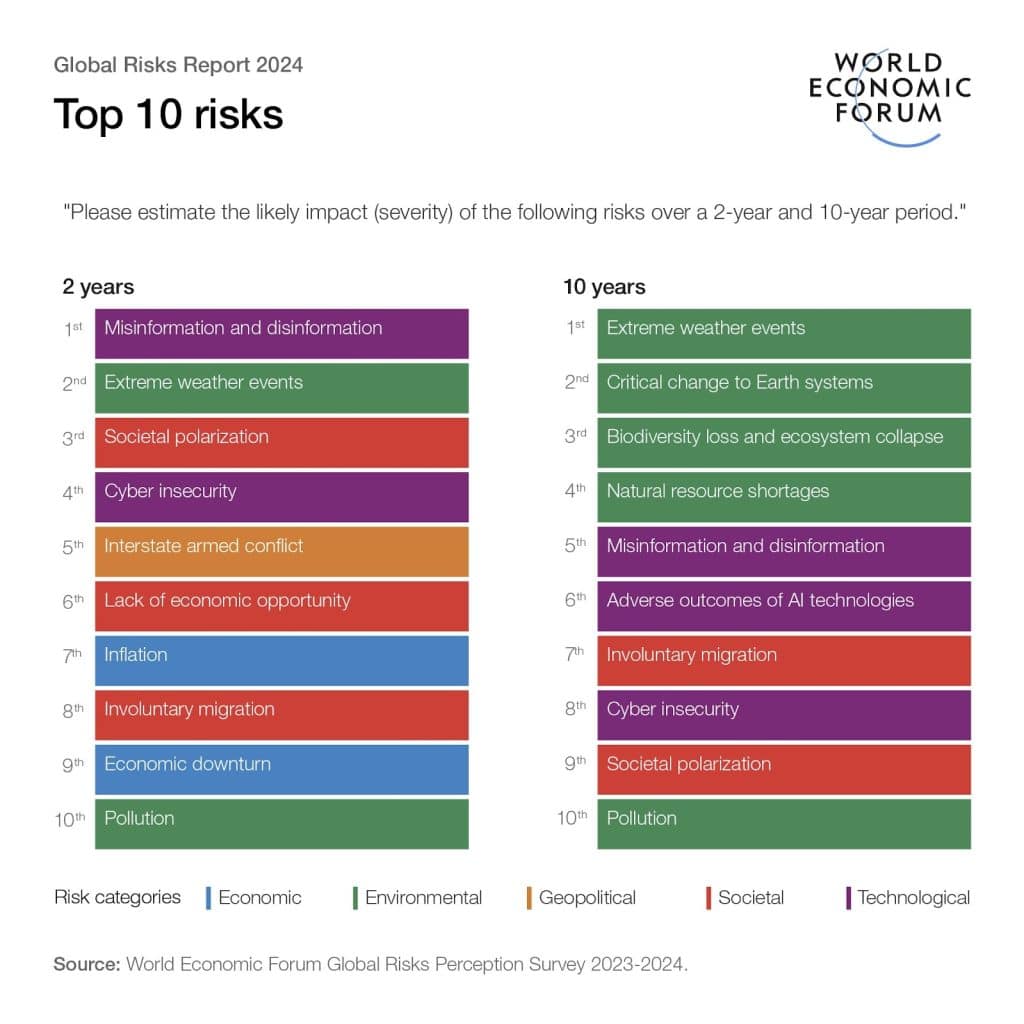

For the second year in a row, the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Report ranked disinformation above extreme weather and armed conflict in terms of threats to global stability. The Canadian government agrees, as do governments all around the world, from Germany to South Korea.

Support The Rover: we get results!

Why? Because online disinformation creates real-world division. It pits citizens against each other, makes us distrust the news and our governments, and poses a persistent threat to societal cohesion and governance.

One click at a time, disinformation endangers democracy.

Many adults can’t tell what’s real online. How can we expect kids to do so, especially when globally, children get their first phone between 10 and 12 years old — long before they’ve developed the critical thinking or emotional regulation needed to navigate the digital world.

This is what worries me when I read about the Quebec government’s well-meaning decision to ban cell phones on school property starting this September: it’s not enough to limit access to phones, we also need our children to build media and digital literacy.

Our kids are being targeted by disinformation.

Right now, our kids are forming their worldview in a sea of disinformation amplified by social media, deepfakes, and bots.

In recent years, disinformation campaigns have started targeting children directly.

A 2018 Wall Street Journal investigation found that YouTube’s algorithm recommends videos “that are more extreme than what the viewer started with.” For example, when researchers searched for “lunar eclipse,” video, they were steered to a video suggesting that Earth is flat. These videos are promoted as “educational,” and are regularly cited by students in class presentations.

Other trends aimed at kids include:

- Holocaust Denial: Teen creators spread Holocaust denial under the guise of “alternative history.” Is it a coincidence that a 2023 poll found that one out of five young people (18–29) say the Holocaust is a myth?

- Misogyny: A 2023 survey conducted on school-aged children in the UK showed that 59% of children aged nine–16 are familiar with Andrew Tate, the self-proclaimed misogynist who is accused of promoting violence against women and girls. Surveys consistently show that a significant minority, often 20–30 per cent,of teenage boys in various countries look up to or have a positive view of such figures.

- The Trad Wives movement isn’t all fresh laundry and homemade pies. It’s an example of online radicalization, and perpetuates conservative values and right-wing ideologies to varying degrees across social media, ranging from xenophobia to patriarchal gender roles, anti-globalism, and white supremacy.

From this to this.

It’s not just that our kids are exposed to harmful content — they create it too. Students have created deepfakes of teachers to mock or falsely accuse them, which have divided towns and led to false arrests. Because once our children go online, age doesn’t matter: a child can spread harmful content with the same reach and impact as an adult.

So what’s the solution?

According to UNESCO, 40 per cent of education systems worldwide — from Cyprus to Turkmenistan — have implemented classroom phone bans. The aim is to:

- Reduce distractions

- Promote social interaction

- Decrease cyberbullying and exposure to harmful content

Studies show positive impacts on focus, classroom behaviour, and social engagement. Cyberbullying drops, but only during school hours. Academic performance improves mainly for students from underserved backgrounds. But the results aren’t universal and sometimes contradict each other, and even these positive outcomes don’t reduce students’ exposure to harmful content.

This year, The Lancet Europe published the first comprehensive study to examine the real-world impact of school smartphone bans on a wide range of adolescent health and educational outcomes. It found no major differences in mental health, sleep, or academic outcomes between schools that banned phones and those that didn’t. Screen time dropped by 40 minutes during school hours, but students made up for it at home, so the average daily screen time stayed the same (four to six hours).

The study concluded that banning phones in school isn’t enough: “comprehensive strategies are needed to address the negative impacts of excessive phone and social media use,” both at school and at home.

Meaning: it will take a village for our children to develop healthier digital habits: media and digital literacy education, parental involvement and consistent school policies.

There is a lot of work to do: a UNICEF survey across 10 countries found that up to three-quarters of children reported feeling unable to judge the veracity of online information, and only 2 per cent had the critical literacy skills needed to distinguish real from fake news.

So, what is the role of school?

Is it to protect our children from distraction so that they can concentrate and learn?

Or is it to teach them to protect themselves by learning healthy digital habits and critical thinking skills, so they can thrive in a world that is increasingly dominated by technology?

Because everything kids learn in school can be undone as soon as they go online.

In addition to the standard curriculum, we need to teach our kids what the 2025 Future of Jobs Report calls the skills of the future: analytical (critical) thinking, resilience, self-awareness, and technological literacy.

The solution already exists

Many countries treat media and digital literacy as a national security issue and embed it into their curricula from kindergarten onward. Finland and Estonia did so to counter Russian propaganda and information warfare; South Korea teaches these in response to North Korean disinformation and digital manipulation. France, the Netherlands and Denmark — there are many countries we can learn from.

These countries and many others don’t just ban phones; they combine phone restrictions with education, balancing limit-setting with skill-building. Students bring their screens into class to analyze propaganda, dissect viral TikToks, question motives behind ads and content, and practice digital citizenship skills.

And it works: studies show that these programs have a dual impact, benefiting both individuals and society as a whole.

Students learn to practice emotional regulation and report better mental health. They create societal resilience when they grow into citizens who can resist disinformation, who are better informed and able to engage in less polarized public debate. Because they trust themselves to spot fake news, they report higher trust in news and institutions such as public health authorities and governments. This, in turn, increases their trust and participation in democratic behaviours, like voting in elections. Or listening to public health authorities and vaccinating their children for measles.

It’s simple: to rebuild trust in each other and in our governments, we need to be able to trust ourselves to tell the difference between what is real and what is false.

These countries recognized that media and digital education are essential to protect children, not to mention their democratic institutions and civic trust.

When will Canada do the same?

Did you like this article? Share it with a friend!

Comments (0)

There are no comments on this article.