Opinion: The Parti Québécois Has Become a Party of Cyberbullies under PSPP

Sources describe online harassment, threats and professional reprisals following their public disagreements with the PQ leader.

Une traduction française de cet article est disponible ici.

“If you don’t change your rhetoric around immigration, I’m going to exterminate your family.”

After this message landed in the inbox of Parti Québécois (PQ) Leader Paul St-Pierre Plamondon last year, his party alerted the police, who quickly traced the source of the death threat. But news of this attack on the leader, his wife and their three young children wasn’t widely known until two months ago.

That’s when the Journal de Montréal published a story about the man who pleaded guilty to uttering that threat. What happened next should concern anyone about the rising climate of online hate in our politics.

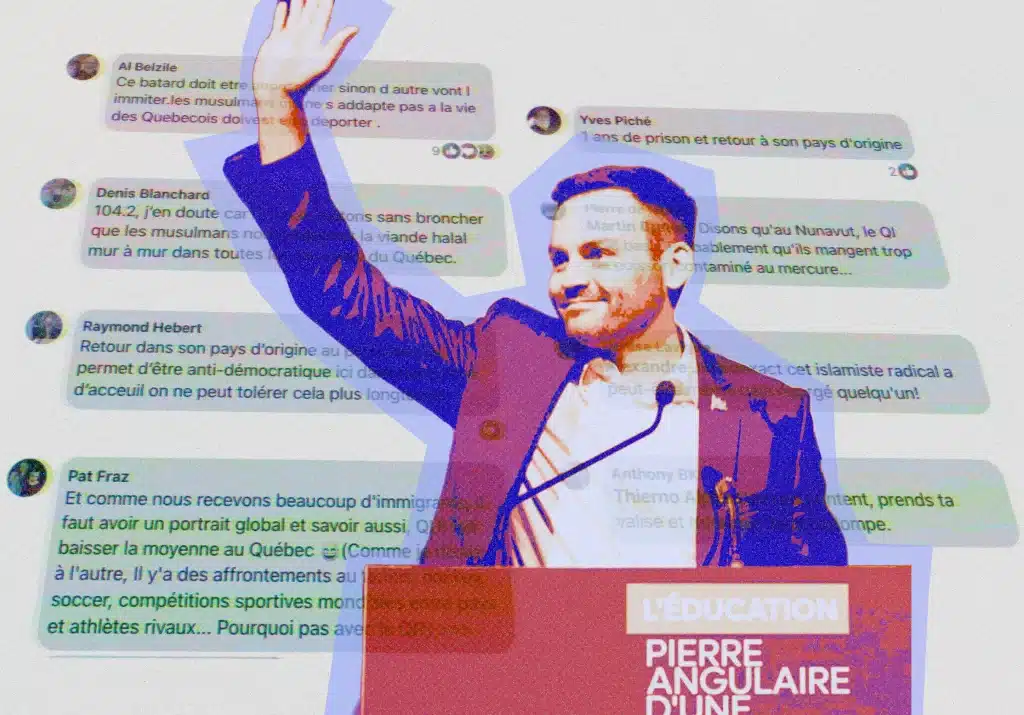

On Oct. 17, PQ member Gaspard Skoda shared screenshots of the article on his Facebook page, sparking a firestorm in the comments section. Without so much as glancing at the story, Skoda’s followers went into attack mode, claiming they knew exactly who was to blame.

“This radical Islamist has probably already slit someone’s throat.”

“This bastard needs to be thrown in jail before others imitate him. Muslims who don’t adapt to life in Quebec should be deported.”

“One year in jail and send him back to his country.”

“Send him back to his country asap.”

“This is terrorism.”

“Let’s find him.”

There was just one problem: the police had already found him, and he wasn’t Muslim or an immigrant. Phillippe Clément-Laberge, the man who pleaded guilty to threatening St-Pierre Plamondon’s family, is a 42-year-old white Quebecer.

And while Skoda and other PQ supporters have depicted him as a product of “the polarizing debate” around immigration, Clément-Laberge appears to have been unwell, and his politics seem difficult to pin down. In the email to St-Pierre Plamondon, he delved into anti-vaccination conspiracy theories and implored the PQ leader to demand Quebec’s Jewish population be deported.

But nowhere in the comments under Skoda’s post does he correct anyone or urge folks to actually read the article he posted. Instead, he seems content to sit back and watch his followers enact imaginary violence on an imaginary immigrant.

One source inside the PQ says Skoda works for the party. But a spokesperson for the PQ did not respond when asked if Skoda is or has been employed by the party.

I found out about Skoda’s post on the Facebook page of author and psychiatrist Marie-Eve Cotton, who called it “profoundly irresponsible.”

Cotton is one of 15 people who spoke to me about enduring relentless online attacks for speaking out against PSPP’s identity politics. In a series of conversations, they each describe a party leader who lets no slight, real or perceived, go unanswered and whose rhetoric around immigration, Islam and the “radical left” has excited something ugly among the party’s most ardent supporters.

Most did not want to go on the record for fear of being swarmed online. But the sources include PQ voters, current and former party members, university professors, and even folks who once considered themselves close to the party leader.

Support your local indie journalists.

***

In the five years since he was elected leader of the PQ, St-Pierre Plamondon has taken the party from fifth in the polls to a commanding first.

The Coalition Avenir Québec government is polling in the toilet, the Liberals are busy knifing each other over a cash-for-votes scandal, and Québec solidaire’s public support is in the single digits as it deals with (another) mutiny.

St-Pierre Plamondon, meanwhile, has a 19-point lead in the polls with an election less than a year away. In all likelihood, he will guide the PQ to its first majority government win since 1998.

Like Jacques Parizeau, St-Pierre Plamondon studied at a prestigious English university, and like Lucien Bouchard, he did some lawyering at Stikeman Elliott. He’s been described, by conservative columnist Mathieu Bock-Côté, as a once-in-a-generation politician.

But he’s also a culture warrior, pushing a brand of nationalism that’s relentlessly combative. And while he is aggressive and unapologetically confrontational, he’s also very sensitive.

On Wednesday, when two prominent artist unions congratulated Marc Miller on becoming the federal minister of culture, St-Pierre Plamondon accused them of “disloyalty” to Quebec and said that he was ashamed of them.

His reasoning? Miller, a bilingual Quebecer, has said he’s tired of the debate surrounding the decline of French in Quebec.

Last week, with the province reeling from labour disputes and legislation that would limit the right of unions to strike, St-Pierre Plamondon was the only major opposition leader not to attend a meeting with the Fédération des travailleurs et travailleuses du Québec.

Why? Because the union’s president criticized the increasingly hostile rhetoric, in our politics, towards immigrants. The comment, which wasn’t even directed at St-Pierre Plamondon, was reason enough for him to miss out on an opportunity to help resolve the labour crisis.

Cotton says this take-no-prisoners approach to politics is poisoning the discourse. And she would know.

In the past few months, when she’s been singled out by members of the PQ, Cotton says she’s had supporters of the party flood her inbox with hateful messages. She claims some have tried to sabotage her career.

“You’re a dumbass.”

“The botox in your face must’ve leaked into your brain.”

“You’re deranged and need psychiatric help.”

At her lowest point, earlier this year, Cotton said she would spend an hour every day deleting comments and messages just like these. The columnist frequently posts about politics on her Facebook page, which she has now had to restrict due to nonstop trolling.

“I’ve been writing on social media like this for 10 years,” Cotton said during a telephone interview. “I’ve criticized psychiatrists who testified during trials. I’ve criticized Zionists, men’s rights activists, the Mayor of Hampstead, who I believe is racist, I’ve criticized plenty of controversial and powerful people and topics. But the only time I had to cut comments on my Facebook page, the only time I received this avalanche of hate, these personal and vulgar messages in my inbox, is when I take on the PQ.

“There’s a level of rage from some supporters that I don’t see in the other parties.”

Cotton, a psychiatrist who treats residential school survivors and their families, has also suffered professional repercussions for speaking out against members of the PQ. This fall, she faced a complaint before the Quebec College of Physicians in connection to a post, on her personal Facebook page, in which she criticized St-Pierre Plamondon.

It was the third time in two years that someone associated with the PQ brought her before the College’s disciplinary tribunals for her Facebook posts. The other complaints were dismissed without merit. Cotton says the only other complaint she’s received, in nearly 30 years of being a doctor, was from an anti-vaccination conspiracy theorist.

“I think that speaks for itself,” she said.

The latest grievance before the Physicians College stems from a September post where Cotton accused St-Pierre Plamondon of practicing Trump-style politics.

She was referencing a full-page ad that ran in Quebec’s largest daily newspaper last summer. In it, the PQ appears to claim there are over 300,000 asylum seekers living in Quebec, making it by far the province with the highest number of refugee claimants. Below the big bold numbers, in smaller font, the ad concedes that these figures actually represent the total number of asylum claims from January 2017 to June 2025.

It doesn’t subtract claims that have been rejected or mention that, when you account for the refugee claimants who moved to other provinces, that number drops below 190,000.

Cotton wasn’t the first or even the most prominent person to criticize St-Pierre Plamondon over the ad. Days earlier, former PQ minister Louise Harel co-signed an open letter calling for Quebec’s political class to tone down the rhetoric on immigration. The letter, published in La Presse, was authored by Anne Michel Meggs, one of Quebec’s foremost experts on immigration.

The PQ leader called their text “a form of intimidation” and implied that these criticisms were connected to jealousy over his party’s rise in the polls. It is, he wrote, “an attempt to confiscate the debate on immigration” and “typical of the radical left.”

Harel, who is 78, served as a cabinet minister under premiers René Lévesque, Lucien Bouchard, Jacques Parizeau, Pierre Marc Johnson and Bernard Landry. Meggs is a former director of research at the Office québécois de la langue française, hardly a federalist institution. She also served on the PQ’s board of directors.

Two sources who knew St-Pierre Plamondon during his early days at the PQ say his views have shifted to the right and hardened. He launched his first bid for party leadership in 2016, standing next to a hijabi woman while he denounced the PQ’s harsh discourse on religious neutrality.

A former associate of the leader says he represented a new way forward for the party after its short and divisive time in government just a few years earlier.

“He publicly debated (conservative columnist) Mathieu Bock-Côté, fighting for the recognition of systemic racism in our society,” the source said. “Now Bock-Côté — a man who has said some horrible things about Muslims, immigrants, feminists and progressives — speaks about him in messianic terms.”

***

Rachel Chagnon, who refused to be interviewed for this story, faced the party’s wrath when she criticized the PQ’s stance on secularism during an appearance on Radio-Canada.

In response to St-Pierre Plamondon’s announcement that a PQ government would adopt a ban on students wearing religious symbols in primary school, Chagnon was unflinching in her criticism.

“Is this a real problem?” Chagnon said during the Sept. 27 broadcast. “Are there thousands of kids showing up to school with ostentatious religious symbols? … Is it so terrible to expose our children to diversity? Is it so horrible that a québécois child should be exposed to a child whose lived experience is different from their Catholic upbringing?

“Do we really need all our children to be the same, from the same mould? And, while we’re at it, why not let them all be blonde with blue eyes?”

The “blonde with blue eyes” comment, which Chagnon later admitted was in poor taste, led St-Pierre Plamondon’s former parliamentary lieutenant, Pascal Berubé, to single out the professor online. He also announced, to his 71,000 followers on X, that he would be filing a complaint with Radio-Canada’s ombudsman.

Though the ombudsman has no authority to sanction guests of the public broadcaster, Chagnon, once a semi-regular panellist on Radio-Canada, has not been invited back since.

As Bérubé cried victim to the ombudsman, former PQ leadership candidate Guy Nantel took to Facebook, where he accused Chagnon of comparing his party to the Nazis. Some of the comments under his post may not have helped Nantel’s argument:

“With the massive immigration Quebecers suffer under Trudeau, these infamous blonde-haired blue-eyed (kids) will soon be placed on the endangered species list… When Levis starts to look like (sic) Bamaco, I worry for the future of our people.”

“We’re in Quebec not Pakistan.”

“I can’t stand those ragheads.”

One commenter posts Chagnon’s email address, tacitly encouraging people to swarm her inbox. Two sources close to the professor say she was targeted by a death threat shortly after that post.

Almost as if it were a coordinated attack — and to be clear, that’s just my opinion —, former PQ MNA Joseph Facal wrote a Journal de Montréal column encouraging the party to contact the university where Chagnon works and “examine” what other recourse it may have against her.

This was an attempt to erase, Chagnon, the dean of UQAM’s school of law and political science, a woman who specializes in how the victims of intimate partner violence fare in our legal system, from the public discourse.

***

Jean-François Hotte, who once considered himself a supporter of the PQ, recently found himself being piled on by the party’s supporters.

In a post on his personal Facebook page, Hotte criticized St-Pierre Plamondon’s rhetoric around “mass migration,” claiming that the term only applies to countries that use immigration to grow their population by 1.5 per cent every year, compared to the 0.5 per cent increase we see in Quebec. For that simple observation, he got flooded with so many comments and messages that he had to restrict his account.

He says they used cherry-picked statistics and, in some cases, appeared to merely cut and paste each other’s arguments in the comments section so they could spam his notifications.

“I’m wondering if it’s a club, a few bad apples, who are maybe not inside the party apparatus but are extremely loyal to the party,” said Hotte, a columnist and marketing specialist. “Let’s call them loyalists. I feel like some of them are using burner accounts to make their numbers look even bigger.

“I’ve worked in web marketing for years. When someone has a fake account, it’s pretty obvious. Guy with 10-20 followers and a Patriote flag as his avatar. Or a pretty girl whose photos are just obviously from a magazine. She has no other online presence except to defend the PQ? That seems weird.

“My gut tells me it’s a 60-year-old guy from Drummondville and not an actual supermodel.”

On the subject of Quebec nationalism, Hotte traces his lineage back to the Patriotes who rebelled against the British at the Battle of St-Eustache in 1837.

He says that, growing up, his heroes were René Lévesque, Jacques Parizeau and the sovereignist filmmaker Pierre Falardeau. But when he criticizes St-Pierre Plamondon’s vision of sovereignty for its lack of inclusivity, his loyalty to the nation is repeatedly questioned.

“When I get messages that are rife with insults and that tell me, ‘Well, if you don’t think like us, you’re not a sovereignist,’ that’s not the PQ I grew up with,” Hotte said.

Like Cotton, Hotte criticizes all the major parties in his columns, but says he’s never received anything close to the backlash he gets when he writes about the PQ. But Hotte and Cotton said the harassment pales in comparison to the violence faced by political commentators who aren’t white.

The Rover spoke to three journalists of colour who say they’ve learned to avoid making any sort of public statement that’s critical of the party.

“Every time, I end up getting people in my inbox telling me to go back to my country,” said one Black journalist, who has worked in radio and television. “I know there are Black members of the PQ, I know that we’ve heard PSPP say everyone is welcome in the party, and that’s great. But to some folks inside the party, and I’m not saying it’s everyone or even a majority, but to some folks, they’re tolerant of diversity as long as we’re quiet and eternally grateful for being allowed in this country.

“I have never been swarmed by followers of the other major parties, and I’ve been critical of them, too. This is a PQ problem. If (St-Pierre Plamondon) isn’t aware of that, he’s not taking a close enough look at his party. And if he does and doesn’t do anything about it, that’s even worse.

“I’ve been attacked for just reporting on the PQ in a way that isn’t flattering enough. Like, I can’t change the facts of a story to better suit your agenda. It’s all a bit ridiculous.”

Alexandre Dumas is a historian, university professor and frequent critic of the PQ.

When he criticized St-Pierre Plamondon online in the past, he said that his exchanges with the PQ leader have always been civil.

“But there’s been an escalation this past year. Not from St-Pierre Plamondon himself, but it definitely hits you after you post about him,” Dumas said. “So the party leader would respond to me publicly, and then a mob would start to gather in my comments and inbox. And then, if any of my followers defend me, they get slammed. It’s insults and derision until they’ve chased you off the platform.

“I can’t tell you with 100 per cent certainty that these are card-carrying members of the PQ. But when I start talking about immigration, when I criticize their vision of secularism, I get a big reaction. And if the post targets St-Pierre Plamondon a bit more directly, the reaction is much, much bigger.

“This never happens when I criticize the other parties. Which I do, often.”

Like Cotton and Hotte, Dumas says he’s been targeted by burner accounts that often use the exact same wording — down to the spelling mistakes — in their comments, regardless of which account they’re using. And like the other columnists, he has had to restrict his Facebook page to avoid being harassed.

“It’s really only when I speak about the PQ that a sort of horde of supporters comes after me. A lot of people accuse me of being associated with Québec solidaire. And while I don’t hide the fact that it’s the party I support, I’m not going to meetings and rallies. I’m not a partisan.”

***

The call came from an unknown number.

“Hello?”

It was St-Pierre Plamondon. He wanted me to take down a tweet I posted, moments earlier, implying his stance on immigration was getting dangerously close to the far-right politics of France. We had never spoken before, and I had never given him my number.

Without being rude, St-Pierre Plamondon placed me in a rhetorical chokehold, reading my own words back to me and providing example after example of why he thought it was off-base.

It was 2020, just a few months before he ascended to party leadership, and I was in the middle of launching The Rover. It seemed ill-advised to get in a pissing match with someone who could debate circles around me, so I tapped out and deleted the post.

When things calmed down, during the call, he offered to publicly debate me, suggesting it might be a bit of fun. To me, arguing against a professional arguer, in my second language, seemed like a sure-fire way to humiliate myself in public. But humiliation was the point. The “baveux” anglophone getting his comeuppance in front of a crowd of PQ supporters, like one of those tomato-can boxers being set up for a knockout on the champion’s road to victory.

The degree to which St-Pierre Plamondon monitored his social media seemed excessive to me at the time, but I could also be an insufferable prick on Twitter, so it’s hard to fault him for that one.

Looking back, I see that this exchange was part of a larger pattern for PSPP.

Something in that man’s ego makes it impossible for him to be the bigger person, to let something roll off his back. Especially when the argument spills into the public arena.

I know this because that’s how I am. Many of us geriatric millennials have lost ourselves in that intoxicating mix of social media dopamine and the adrenaline of online arguing. And, to me, undoing that impulse has taken years. It was a factor in my decision to quit drinking 16 months ago and leave the insanity of Twitter fights behind.

I don’t see that degree of introspection in the man who, barring a disaster, will be the premier of Canada’s second-largest province come next fall. And why would he change? Despite being lampooned by some of Quebec’s most prominent intellectuals, St-Pierre Plamondon is far and away the most popular party leader in the province.

In October, former Quebec City mayor Régis Labeaume penned an editorial where he accused the PQ leader of using hateful rhetoric against Muslims and immigrants to win over the “white francophone” vote. St-Pierre Plamondon, as he often does, demanded that La Presse allow him space in the newspaper so he could refute the “defamatory” allegations. The paper refused.

Over the next few days, he was pilloried in the press as a crybaby, and even the Journal de Montréal — erstwhile supporters of the leader — published a column denouncing his “obsession with being right” and urging him to toughen up. After all, this is the same politician who implies that his opponents are traitors and radical leftists, and whose followers routinely defame people online.

Labeaume, whose politics are aggressively centrist, isn’t what I would consider a radical. But polls show St-Pierre Plamondon has a 13-point lead in the former mayor’s city. From the PQ’s perspective, it’s hard to argue with results.

I am not ignorant of what will happen to me next.

There is a good chance this essay earns me a visit from the troll farm, and they will argue, as they always do, that I’m an anglo who hates francophones, lives in a bubble and doesn’t understand Quebec.

To this, I would merely say that I grew up in the heart of PQ territory. My elementary school, École Notre-Dame in St-Eustache, was a half-block from the church where the Patriotes made their last stand during the 1837 uprising.

While St-Pierre Plamondon attended Collège André-Grasset, a prestigious private CEGEP, I spent my college years working on construction sites with lifelong supporters of the PQ.

It’s hard not to bond with someone who spends a 12-hour shift next to you, sawing concrete and pouring hot tar in the beating sun. These men were and remain my friends. Over that eight-year stretch, we went on the road together for weeks at a time, argued relentlessly about politics, played untold hands of the card game “asshole” by the side of the road and in construction trailers and shared countless meals. When one of us was short a few bucks to buy ourselves lunch on the road, the others chipped in to pay for it.

Richard Samson, a lifelong péquiste and one of the finest roofers I ever worked for, used to call my brother Vince and me the “two five fours” in reference to an old TV commercial about learning English through Quebec’s Institut linguistique. It would end, he said, with a francophone calling out the Institut’s number in English: “Two five four, six oh one one.” Out there, on the job sites, we didn’t see each other as anglophones and francophones. We were workers.

During the years of la Grande Noirceur, my maternal grandfather, a francophone, was placed in a sanitarium where they treated him for tuberculosis. All of the patients, many of whom had contracted the disease by living in crowded apartments, were francophones. The doctors who treated them spoke not a word of French.

I’m not insensitive to that reality.

There was a time when I might even have been convinced to vote yes in a referendum to separate from Canada. I don’t have a particular attachment to the country, its history of colonial violence and its broken constitution. But I do love the people in it, regardless of what language they speak, country they came from or God they pray to. We are, after all, neighbours.

I think St-Pierre Plamondon would do well to consider that.

Excellent article. Les propos de Paul St-Pierre Plamondon ne passent pas avec plusieurs indépendantistes et ne voteraient jamais pour lui ou pour la séparation du Québec s’il était en poste pour le faire. La grande majorité des Québécois ne partagent pas son attitude envers les immigrants,

Toujours “on point”, Chris!

PSPP LE CHARLIE KIRK DES PAUVRES….

Après ça vous vous demandez pourquoi on ne vous prend pas au sérieux…

Moi aussi je l’ai publié sur BlueSky.

“One source inside the PQ says Skoda works for the party. But a spokesperson for the PQ did not respond when asked if Skoda is or has been employed by the party.”

Skoda était adjoint exécutif en 2023, puis adjoint exécutif et gestionnaire de projets en 2024. On peut trouver l’information sur la page du PQ “Permanence” à l’aide de Wayback Machine, car elle est maintenant supprimée.

Wow, merci de la précision,.

Il était adjoint exécutif en 2023:

https://web.archive.org/web/20231023153506/https://pq.org/permanence/

En 2024, adjoint exécutif et gestionnaire de projets:

https://web.archive.org/web/20240525152604/https://pq.org/permanence/

lol

Merci pour ça.

Excellent commentaire Chris. Je l’ai partagé sur Bluesky.