The Killing of Nooran and the End of Community Policing

The police shooting of an unarmed teen should call into question the sterling public image of the Longueuil police force and the role of countless reporters and elected officials in creating this image.

The killing of Nooran Rezayi by the Longueuil police force this week has once again left a community in shock, struggling with grief, and searching for answers.

Nooran’s death comes on the heels of two police killings in Montreal in the spring and a pattern of police violence and impunity with no clear beginning and no end in sight.

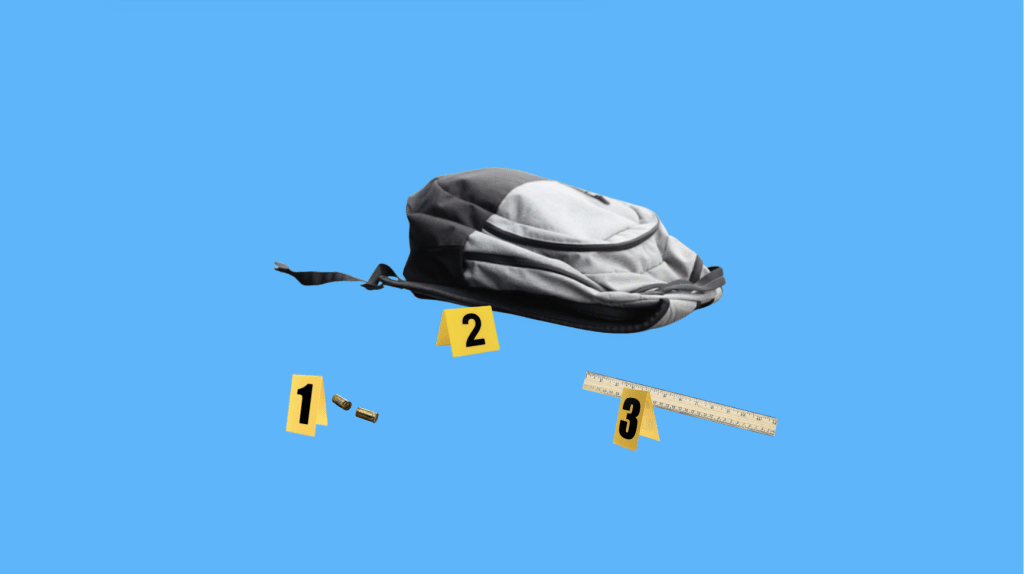

Nooran, just 15 years old, was with a group of friends on Sunday afternoon when two police cars, reportedly responding to a 911 call, arrived on the scene. As the rest of the group scattered, Nooran obeyed police orders to stay put. When police ordered him to show his hands, Nooran complied. One officer, for reasons that remain unclear and incomprehensible, fired two shots at Nooran, ending his short life.

The killing of an unarmed teenager should call into question the sterling public image of the Longueuil police force and the role of countless reporters and elected officials in creating this image. It is hard to think of a police force that has received more glowing media coverage in recent years than Longueuil — none of it deserved.

The positive spin began when Fady Dagher (the current SPVM police chief) was hired as police chief in 2017 and accelerated greatly in the fall of 2021, when the force introduced a new community policing program known as the Réseau d’aide sociale et organisationelle (RÉSO).

The RÉSO program, enabled by $3.6 million in funding from the Quebec government, saw a select group of police officers spend six weeks visiting community organizations, without their uniform and without their gun. The aim of the program, according to Dagher, was to bridge the gap between the police and the community, turn police officers into “social actors,” and “change the mandate and mission of police work.”

The introduction of RÉSO made the Longueuil police force a media darling and Dagher a kind of celebrity in Quebec. In a context still shaped by the historic 2020 protests against police violence and widespread calls to defund the police, the program was described by reporters and elected officials as an alternative path forward – one that transformed the police, without touching its budget or power. Radio-Canada even produced a 10-part television series on RÉSO called Police Avant-Gardiste.

As many critics noted at the time (myself included), similar efforts at bringing police and community members closer together had been tried in the past. It was less a “new model,” in fact, than the continuation of the “community policing” model that was introduced in Quebec and much of the world in the 1980s.

Like RÉSO, community policing involves initiatives like multicultural training and police-community partnerships alongside continued and often increased police repression. As the long list of people killed by police since the 1980s demonstrates, community policing does nothing to rein in racial profiling or police violence.

Indeed, just as the RÉSO program was beginning, the Montreal region was the focus of a widening moral panic about gun crime and street gangs — a panic, fed by media outlets and police organizations, that wildly exaggerated the level of gun crime taking place and the amount of gun crime attributable to gangs. In response, the Quebec government introduced a $74 million new funding scheme for anti-gun operations, with $3 million flowing to Longueuil. Ironically, Longueuil’s new anti-gun operation was launched in the same month and with roughly the same financial support as the RÉSO program that was supposedly changing the mandate and mission of police work.

Not surprisingly, the new anti-gun operation resulted in a massive increase in random police street checks. In the first three months of the operation, the police carried out 836 street checks across the territory. In the next two years, the number of street checks remained high — 1,074 in 2023 and 821 in 2024 — with “the great majority (72 per cent)” attributable to the anti-gun operation.

In this period of intensified street checks, Black people were twice as likely to be stopped by police as white people, while Arabs were 1.7 times more likely to be stopped. As the media were celebrating a “new model” of policing, then, Longueuil was carrying out a very conventional police operation – an operation ignited by a moral panic about guns and fixated on the imagined dangers of Black and Arab people.

It may have been this operation that put certain Longueuil police officers in regular contact with Nooran and his friends. In an interview posted on Tuesday, a friend of Nooran’s claimed the officer who fired the fatal shots had been harassing them for months and had ticketed them unjustifiably.

“We already knew the officer,” the friend said. “Every time (we encountered him), he made racist remarks, insulted us, yelled at us, abused his power.”

The officer, according to the friend, devoted special attention to Nooran: “Several times, (the officer) came, saw Nooran, and harassed him for no reason.”

Given this background, the killing of Nooran should make the usual political response in these situations impossible. Year after year, killing after killing, police organizations and elected officials tell us to have faith and patience. Reforms will be introduced. The police will receive better training, more racialized police officers will be hired, and new efforts will be made to bring the police and the community closer together. The police might even be given “a new mandate and a new mission.”

This response should be impossible because the Longueuil police force is the embodiment of police reform, the “avant-garde” of community-oriented policing. It was this police force, a reformed police force, that burdened Black and Arab people with oppressive police stops, that harassed a group of teenagers for months, and that finally killed Nooran on a Sunday afternoon.

We do not need more police reform or a new police mandate. We need fewer police, we need a transfer of funding from police forces to the many other services and programs that keep people safe, and we need Nooran’s killer to find another line of work.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that four police cars responded to the call that resulted in Nooran Rezayi’s killing. In fact, it was two police cars totalling four officers who responded. The Rover regrets the error.

We need public services, NOT policing.

Community policing has proved itself a sham. It is pure public relations, where bikes on cops use their bikes as weapons to suppress protest. And even crime is not the concern of state power, because of anyone ever wanted to drop crime rates, statistics have long proved that housing, health and other supports for life are the key to healthy communities (read: safe communities-low crime). There are multitudes of studies that substantiate my assertion. However, historically, countless fascist states throughout the past 200 years have proven that to control society and therefore any dissent by the people, you can never have enough police. The priority is not low crime, the priority is control over all populations, to maintain a sense of fear to restrict dissent and any threat of rebellion.

“Black people were twice as likely to be stopped by police as white people, while Arabs were 1.7 times more likely to be stopped”.

I have a beef with this statistic. I bet the vast majority of people “spot checked’ by the police are between 13-30ish. So we need to compare this group to it’s equivalent ‘white’ age group to get an accurate number.

A whole bunch of harmless white retirees messes up the stats and makes it look like the police force are targeting people of colour. And perhaps, youth of colour do commit more crimes than non-racialized youth. Who knows? Do we keep or share those stats? Beats me.

There is lies, damn lies, and statistics.

Des gens disent que le policier a agit avec les informations qu’il avait, que ça s’explique. Il avait un groupe de jeunes assez nombreux devant lui, et la situation pouvait être menaçante, de plus l’appel au 911 mentionnait la présence potentielle d’une arme. OK, mais est-ce que ça veut dire qu’il suffit de dire qu’on croit avoir vu une arme, dans un événement public, pour que la police tire sur un participant? Je trouve ça excessivement inquiétant que les gens trouvent que c’est une justification suffisante pour avoir tiré sans autres informations VÉRIFIÉES sur place. La police n’est pas une personne comme les autres, elle détient une arme en plus de l’autorité. On ne peut pas dire que c’est normal d’avoir réagit si vite, car ils sont censés être formé pour ne pas réagir comme n’importe qui le ferait. Le concept de force nécessaire est très biaisé et devrait être revu. Force nécessaire pour quoi? Si le policier se sent en danger, pourquoi ne reste-t-il pas derrière son auto? S’il s’est senti assez confiant pour s’approcher, pourquoi a-t-il jugé si urgent de tirer? Très inquiétant comme événement, processus, procédures, philosophie….

Linda, I trust you mean the cops when you say ‘most often, the problem arises from addiction, mental health and emotional distress’. What is preventing change is that ACAB. There is no ‘fixing’ or ‘improving’ the system. Abolition is the only way. And yes, it will take time due to these power hungry, violent, state enforcers and protectors of capital.

I agree that we need less police and more trained community experts in health and welfare when we are dealing with a majority of situations that arise. Most often the problem arises from addiction, mental health and emotional distress. Lives can be saved and situations like what happened in Longueuil avoided. But we have known this for some time and I don’t understand what is preventing the change unless police do not want to give up their control.