Why is Quebec Selling Public Land During a Housing Crisis?

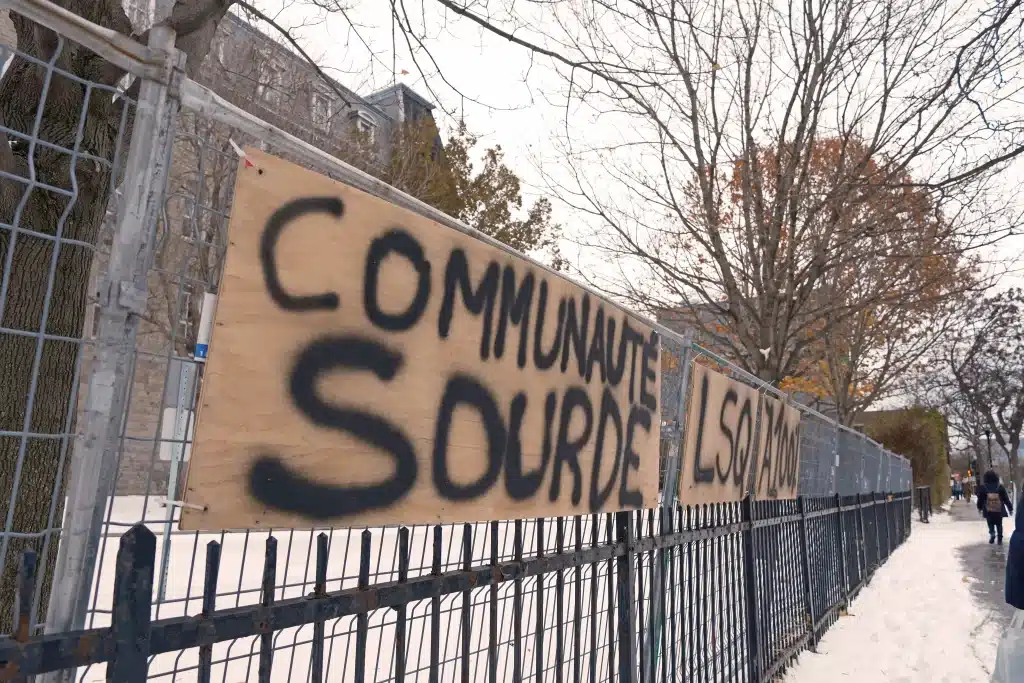

After the Institut des Sourdes-Muettes was sold to a developer to save its heritage, community organizers are wondering how the province let this happen again.

In the southern end of the Plateau, on the corner of Saint-Denis St. and Cherrier St., is a stone building that has faded into the background of the neighbourhood.

Like many of Montreal’s abandoned heritage buildings, few Montrealers know its history.

The aging structure was once the Institut des Sourdes-Muettes de Montréal, a boarding school for deaf girls, established in 1864. Most of the students lived at the school, where they learned the catechism and how to read and write. It was run by the Sisters of Providence until it shut down in 1975, when Quebec gained secular control over the educational system.

Since then, the building has been occasionally used as offices for various organizations until it was abandoned in 2015.

Over the last several years, the building has been decaying, its wooden verandas and oak stairway breaking down as the ornate columns inside grow obscure. It’s a mystery why the province decided to leave this building abandoned without maintaining its integrity (which was decently preserved until 2015) and repurposing it as a community space, especially for the deaf community.

In 2019, Maison Ludivine Lachance was established by community organizations to reclaim the Institut des Sourdes-Muettes. The non-profit was born out of the vision to revitalize the building to be a living space, a community centre and historical monument for the deaf community in Montreal.

When Marie-Josée Richard imagines how she wants the Institut to be revived, she pictures it as a safe haven. There are fully adapted, affordable apartments for deaf people, but the building could house anyone — families and students, too. There’s also a community room to host holiday celebrations and game nights. There could be sign language classes open to anyone in the building, free of charge.

There could be offices for local non-profits. A part of the building could house a museum commemorating the history of the deaf community in Montreal.

For Richard, the Institut is the last building in the city that holds the history of the deaf community in Montreal — a lot of the other buildings related to their history have been destroyed or converted into condos.

“This whole building, I’ve always said, has a spirit,” says Richard.

Support your local indie journalists.

There is only one affordable housing complex for deaf people in all of Quebec. It is the Maison des Sourds in Montreal with 60 units and a capacity of only 225 people.

Richard says that it’s often a fear for someone who is deaf when trying to find accommodation that the landlord or neighbours might take advantage of them because of the language barrier. For many deaf folks, French is a second language, and the syntax of Quebec Sign Language can be extremely confusing. For instance, to sign “I will take my medication after eating,” it might be understood as “I will take my medication and then eat afterwards.”

These kinds of minor miscommunications can be detrimental when trying to discuss matters with a landlord. An apartment also has to be adapted so that doorbells and security systems, such as fire alarms and carbon monoxide detectors, provide visual alerts in each room rather than audio alerts in only one spot.

“Social housing is important because it also builds community — and the deaf community really needs to be together,” Richard said. “They can’t really chit chat with people when they take the bus or go grocery shopping since nobody really (knows sign language), so they feel a lot of isolation.”

For the last decade, a small but dogged group of community members has been fighting to have this building reclaimed by the public rather than allowing it to rot, forgotten in the province’s hands. With the work of local community groups like the Corporation de développement communautaire (CDC) Plateau-Mont-Royal, there’s been a major mobilization in the neighbourhood to fight for the land to belong to the people and to preserve the site’s social, public, and community character.

After years of community consultations, the Société québécoise des infrastructures (SQI) has sold the site to Residia, a private developer, to build condos and restore the majority of the historic building.

Yet Hélie-Martel says that we are not talking enough about what it means for this large piece of public land in a central location to be sold to a private company. “And for what? For someone to be making more money? There’s more to this than saving heritage,” she says.

CDC Plateau-Mont-Royal member Anaïs Hélie-Martel says that the site should’ve remained 100 per cent public, and that this is not the way to alleviate Montreal’s worsening housing crisis.

Since 2019, the average rent in Montreal has shot up by 71 per cent. What used to be the average asking price of $1,130 for a two-bedroom apartment just six years ago has gone up to $1,930 at the start of this year. In Quebec, rent inflation is at 9.3 per cent — almost double the national average of 4.7 per cent.

Residia’s project proposes two new condominium towers on the site that will pollute the quaint Plateau skyline. The proposed development does include commitments to reserve sections of the site for family housing (13 per cent), affordable housing (15 per cent) and social housing (16 per cent), but the majority of the development will be market-rate condo units. The entire project is said to include 884 units, green roofs, a memorial garden, two pedestrian walkways, 305 underground parking spaces, and a public plaza on the Saint-Denis St. side of the building.

The developer will also preserve and restore the heritage pavilions of the main building, including the Notre-Dame-du-Bon-Conseil Chapel in the heart of the site, the limestone facades, the convent buildings, and the interior courtyards.

“The selected project was the one that ensured the greatest preservation of the heritage complex, to which the deaf community has a strong attachment,” said the former city counsellor for Plateau-Mont-Royal, Marie Plourde, in a statement to The Rover.

“While we would have preferred the project to be entirely public, the selected approach is considered to strike a balance between our various objectives: heritage preservation, increasing the supply of social and affordable housing, and, most importantly, preventing the prolonged abandonment of the building from eventually leading to its demolition.”

Heritage Montreal, an organization advocating for the preservation of historic sites and buildings in Montreal, also expressed its support for the project, along with relief that action has been taken before the building deteriorates even further.

Yet Hélie-Martel says that we are not talking enough about what it means for this large piece of public land in a central location to be sold to a private company. “And for what? For someone to be making more money? There’s more to this than saving heritage,” she says.

Normally, when a developer that has promised to create social housing units can no longer do so, they either have to pay the city a fee or give land that can be made into social housing. According to a 2023 CBC report, most developers between 2021 and 2023 opted to pay the city rather than build social housing units, which are directed into a social housing fund. There is $63 million in this fund, according to the city.

More recently, the Van Horne warehouse, an iconic building in the Mile-End, has been sold to a developer that previously released its plan to transform the site into a hotel and commercial spaces. However, with significant community pushback, the borough has asked the developer to reimagine a plan for the building that would include stronger community and social elements in the project. In a revised plan, the developers now also include affordable artist studios and a shared gallery space.

In Quebec, it’s the SQI that owns and often acquires much of the public properties, such as the Institut des Sourdes-Muettes, and has the power over its future, while the City of Montreal has little say in the matter. However, Nathan McDonnell and Paul Bode from the Comité des citoyen·ne·s de Milton Parc (CCMP) say that while the City doesn’t have the kind of funding to purchase and develop sites, it does still have agency in one main area.

“Any redevelopment has to pass through the city, who has to approve any kind of plans, especially for changing zoning laws, so that’s their biggest form of leverage to kind of force a strong criteria in certain things like social housing,” says McDonnell.

Community organizers at CCMP, like McDonnell, are not new to the fight to defend public land from developers. For the last two decades, they’ve been advocating for the future of the Royal Victoria Hospital and the Hôtel-Dieu de Montréal to remain in the public domain.

Both sites were provincially owned and under threat of being sold to private developers. Half of the Royal Victoria Hospital was finally transferred to McGill University, while the Hôtel-Dieu was partially used as an emergency shelter for a few years. It now operates as a large clinic.

“A big kind of anxiety I have in this whole process is that basically a similar thing will be reproduced for the Hôtel Dieu hospital, and the second half of the Royal Vic hospital,” says McDonnell.

Bode, who has worked extensively in restoring and repurposing religious sites in Montreal, points to the Cité-des-Hospitalières as an example of the city being proactive in fighting for public land.

When the nuns who ran the site wanted to get rid of it, the city of Montreal jumped to acquire the massive, historic building and transform it into a shared community site for nonprofits, artists, and community groups. The city got a social purpose organizer called Entrimise to operate this site for it. However, this site, according to Bode, was run by nuns who kept it in good condition, and it therefore didn’t require the high costs of restoration that come with a site like the Institut des Sourdes-Muettes.

Both Bode and McDonnell describe the cycle of selling abandoned sites to developers as a situation in which community groups are held hostage, with no other means of action, because it’s either that or let the building deteriorate. When the province doesn’t have the funds to foot the bill for a place like the Institut, the only way to save it becomes to privatize.

“This is going to be the single largest real estate project the Plateau has seen in forever, essentially,” says Bode. “I generally want to hold the government to a higher standard in the way that it maintains its buildings and the purposes they put them towards. I think that the city has to take a bigger role in these things, because we simply can’t leave it up to the provincial government.”

Thank you for this article !!